Do nominally democratic institutions help dictators stay in power by lowering the risk of coups d’état? Jun Koga Sudduth analyses different types of coup, and their effects. In so doing, she challenges the conventional wisdom that democratic institutions reduce the likelihood of dictators being overthrown

Nominally democratic institutions such as political parties and legislatures are a common feature of autocracies. Data reveal that ruling parties exist in approximately 73% of autocracy-year observations between 1946 and 2010 (China 1946 is one observational unit, Iraq 2010 another, and so on), while legislatures exist in approximately 78%.

The widely held view among scholars is that dictators create these nominally democratic institutions. This is because they help them, and their authoritarian regimes, stay in power by reducing the risk of coups.

conventional wisdom holds that dictators create nominally democratic institutions to keep their authoritarian regimes in power

A coup d’état is an attempt by individuals within the state apparatus to remove the sitting head of government using unconstitutional means. An overwhelming majority of dictators lose power via coups rather than other types of non-constitutional removal. Given this, the coup-preventing role of nominally democratic institutions should be a welcome finding for dictators.

My Comparative Political Studies article with Nam Kyu Kim challenges this view. In it, I argue that the effectiveness of nominally democratic institutions in deterring coups in dictatorships depends on the types of plotters and their political goals.

Recent work highlights that coups in autocracies take two different forms: regime-changing coups and reshuffling coups.

Regime-changing coups change entirely the ruling elites in power, along with the formal and informal rules for leadership selection and policies. For example, the military coups in Egypt in 1952, Iraq in 1958, and Libya in 1969 were regime-changing coups. In these instances, military coups ousted the royal family and ended dynastic rule.

Reshuffling coups, on the other hand, merely replace the incumbent leader with another member of the same ruling elite. Thus, they preserve the regime intact. Early 1970s coups in Argentina replaced only the junta leaders. These coups, then, fall into the reshuffling category because the same military junta continued to rule in the aftermath.

The role of nominally democratic institutions in deterring coups is much more limited than previously thought

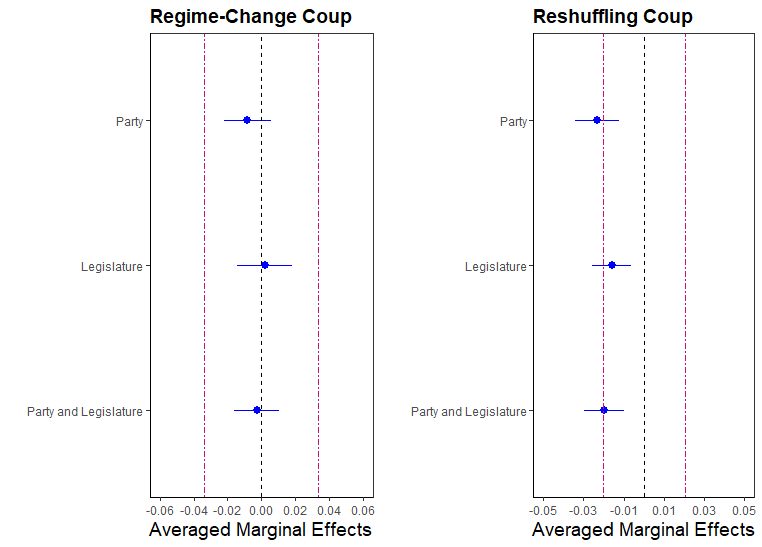

While nominally democratic institutions reduce reshuffling coups, they do not diminish the risk of regime-changing coups. The role of nominally democratic institutions in deterring coups is much more limited than previously thought, applying to less than 38% of coup attempts.

The right panel above shows that ruling parties and legislatures have negative and significant effects on reshuffling coups. On regime-changing coups, they have insignificant and negligible impacts. The confidence intervals include zero and lie entirely within the region of substantively negligible effects specified by red lines on the left panel.

So why do we see such divergent effects of institutions on different types of coups in dictatorships?

Political parties and legislatures prevent reshuffling coups because they enable ruling elites to address their concerns over a dictator’s opportunism and incompetence.

Ruling elites hold key positions with the power to influence the regime’s decision-making and control leader selection. Elites aim to make dictators commit to share enough power with them, and to punish opportunistic or incompetent dictators.

Nominally democratic institutions address elites' concerns by facilitating collective action and improving the transparency of decision-making. They also provide institutional means for elites to achieve their goals. This makes it less likely that elites will need to punish the leader using violent and risky means such as coups.

However, the same logic does not apply to regime-change coups.

Plotters of regime-change coups aim for a total regime overthrow. Their goals are to change entirely the group of ruling elites, the rules for leader selection, and policy decisions. Because such goals are incompatible with existing institutions’ values and rules, institutions cannot help plotters achieve such goals.

Nominally democratic institutions do not provide a peaceful means of achieving regime change. Thus, they do not reduce plotters' willingness to use violent and unconstitutional means, such as coups, to pursue their goals.

Nominally democratic institutions do not provide a peaceful means of achieving regime change

Furthermore, while nominally democratic institutions mobilise mass support for the regime and deter regime-changing coups, this deterrent is offset by those institutions’ fomenting grievances among plotters.

Ruling parties and legislatures can mobilise mass support toward the incumbent regime and increase the likelihood of widespread post-coup protests against attempted coups. At the same time, those institutions increase the feeling of relative deprivation and grievances held by potential plotters of regime-change coups. As these plotters typically cannot even participate in nominally democratic institutions, they would not obtain institutional benefits, thus increasing their grievances and frustration against the regime.

The conventional wisdom that nominally democratic institutions reduce the risk of coups applies only to reshuffling coups, not regime-change coups.

Dictators should be aware that the creation of nominally democratic institutions is, therefore, not as effective in reducing coup risk as scholars have previously argued: more than 62% of coups between 1946 and 2010 resulted in regime change.