All the polls are pointing to a victory for Joe Biden in the 2020 American presidential election. Yet, writes Richard Johnson, the inherent disproportionality of the American presidential electoral system suggests that Biden, like Hillary Clinton before him, could end up winning the popular vote but losing the Electoral College vote – and thus the presidency

Joe Biden has enjoyed a robust lead in the national polls since he secured his party’s nomination earlier this year. Under most electoral systems, a candidate with Biden’s polling lead could feel quite confident about his or her election prospects. But, in the United States, a presidential candidate’s polling lead is imprecisely related to their chances of becoming president.

There is reason to believe that if Trump were re-elected, his popular vote deficit would be even worse than in 2016

As Hillary Clinton experienced in 2016, Biden could feasibly win millions more votes than Donald Trump and still lose the election. There is reason to believe that if Trump were re-elected, his popular vote deficit would be even worse than in 2016.

A US presidential election consists of fifty-one different first-past-the-post contests of varying importance depending on the size and partisan competitiveness of the state.

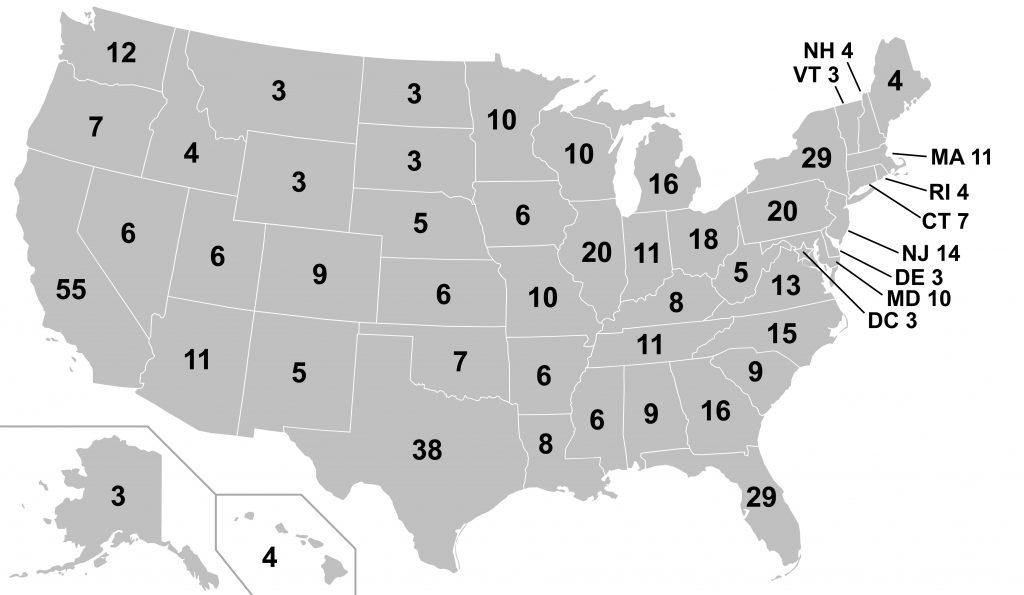

Each state gets a set number of electoral college votes (EVs) based on a formula updated every ten years: a baseline of two EVs plus a number of EVs equivalent to the number of members elected from a state to the US House of Representatives.

Wyoming, which has just one US House member, is allocated three electoral college votes, while California, which sends 53 representatives to the House, has 55 electoral college votes. There are 538 electoral college votes, and a winning candidate must secure an absolute majority of 270.

This system only loosely reflects population differences in the states and can generate a substantial degree of disproportionality in several ways.

First, the electoral college formula imposes a ceiling and floor on the EVs allocated to each state, which boosts small states at the expense of populous states. No state can receive fewer than three EVs, even though some states should receive fewer according to true proportionality.

For example, California has a population of nearly 40 million, whereas Wyoming has a population of less than 600,000. California is 68 times more populous than Wyoming, but it only has 18 times the number of electoral college votes.

a candidate can win 100% of a state's electoral votes with a majority of just one vote over their opponent

This means that candidates who do better in low-population, rural states will perform disproportionately well in the electoral college compared to candidates whose electoral base is found in populous states with big cities and suburbs.

Second, the number of electoral college votes allocated to a state is updated every ten years. The 2020 election will be relying on population surveys conducted in 2010. This lag over time disproportionately underrepresents states which have experienced population growth in the last decade, while giving additional weight to states whose populations have experienced relative (or even absolute) decline.

Since the 2010 census, the population of West Virginia, for example, has declined by about 3%, whereas the state of Washington has grown by over 13%. Washington is now 4.2 times the size of West Virginia, whereas ten years ago, it was only 3.6 times the size. The electoral college will not take account of these population changes until 2024.

A third source of disproportionately is in the ‘winner-take-all’ allocation of states’ electoral votes.

Each state is allowed by the Constitution to set its own rules for allocating its electoral votes. Forty-eight states have chosen to award all of their electoral votes to the plurality winner of their state. Two states (Maine and Nebraska) each give two votes to the state popular vote winners, and the remaining electoral votes are allocated on a first-past-the-post basis in the state’s congressional districts.

With these two exceptions aside, a candidate can win 100% of a state's electoral votes with a majority of just one vote over their opponent.

This winner-take-all dynamic introduces the greatest amount of disproportionality in the electoral college system. It means that candidates who accumulate large majorities in certain states can boost their national popular vote standing without fundamentally altering their performance in the electoral college.

In 2016 Hillary Clinton won California with 61.7% of the vote, giving her a majority over Donald Trump of 4,269,978. In effect, 4,269,977 of these votes were wasted. These ‘wasted votes’, however, did give Hillary Clinton the cold comfort of her national popular vote victory of 2,868,686 million votes.

Could Biden win by an even greater margin in the national popular vote than Clinton but still lose the electoral college to Donald Trump? In a word, yes.

There are a couple of additional reasons to think that the electoral college could generate an even more disproportionate outcome this time. The first is that Biden is likely to win California by an even greater margin than Hillary Clinton did. Clinton defeated Trump by 30 percentage points, but Biden is leading Trump in California by 36 points. Biden could feasibly win California by 5 million votes, which would boost his national popular vote lead but contribute nothing to his electoral vote strength.

In 2016 Hillary Clinton won California with 61.7% of the vote, giving her a majority over Donald Trump of 4,269,978. In effect, 4,269,977 of these votes were wasted

The second is that this time turnout in ‘blue states’ like California, New York, and Massachusetts is expected to be very high, and third party support is expected to be much lower. Left-wingers in ‘safe’ blue states last time could cast a protest vote against Hillary Clinton for the Greens, but this time the polls suggest that they will stay loyal to the Democratic nominee.

Finally, Trump is performing worse than in 2016, but maybe not badly enough to deny him re-election. Trump won Texas with a majority of 807,179 votes last time. These votes were effectively wasted. This time, Trump is expected to win Texas much more narrowly, perhaps by only a couple percentage points.

Feasibly, 800,000 fewer Texans could vote for Trump and, other things being equal, he’d still win the state. Trump’s national popular vote lead would take a substantial hit, but from an electoral college perspective, this would be an ‘efficient’ victory with few wasted votes.

In sum, the electoral college structurally undervalues populous states and states with growing populations, especially at this point in the census cycle.

Additionally, the partisan dynamics of very large states like California and New York mean that Biden is likely to accumulate millions of wasted votes that boost his national polling lead but offer no advantage in the electoral college.

Biden is likely to accumulate millions of wasted votes that boost his national polling lead but offer no advantage in the electoral college

Trump, on the other hand, is not likely to ‘waste’ many votes in the red states. If he wins, it will be by narrow (‘efficient’) majorities in large states like Texas, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania.

While a Biden victory is still the most likely outcome, a still-possible Trump victory will benefit from even greater electoral college disproportionality.