Examining the first 99 entries in our Science of Democracy series, Alex Prior identifies an asymmetry between references to people (demos) and power (kratos). Through a discussion of this asymmetry and its possible causes, he calls for increased attention to power, in the sense of its ability to effect change

More than a hundred essays have now been published in The Loop's thriving Science of Democracy series. Such a broad body of scholarship reveals a consistent theme about how variously democracy can be understood and applied. The thousands of adjective-types (3,539 and counting) collected by Jean-Paul Gagnon continue to enrich discussions about the plethora of contexts in which we identify democracy and democratisation.

What conclusions can we draw so far from these writings? And how do those conclusions relate to broader questions about democracy, as a concept and a process? To find out, I ran NVivo tests on the first 99 entries in the series.

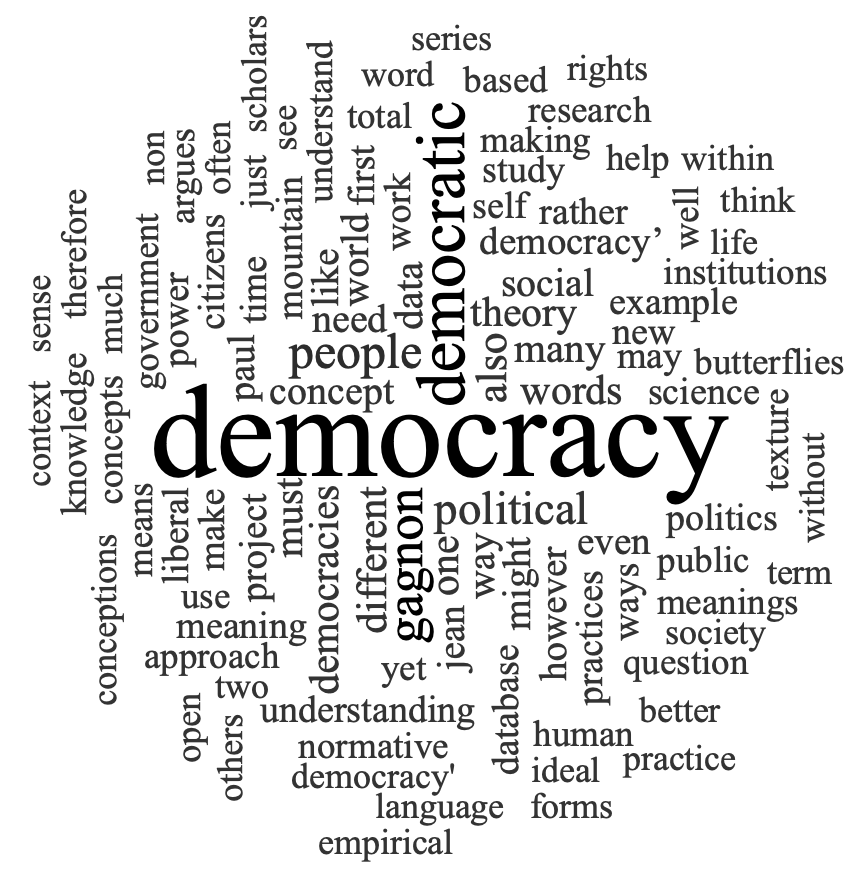

There are many potential points of entry through which to tackle these questions. I focused on democracy which was, unsurprisingly, the most frequently-used term. The word comprises two components: demos (people) and kratos (power), both of which are worth exploring vis-à-vis the essays. Below, a word cloud reveals word frequency across the entries. Most-used terms render largest:

The prevalence of people, fourth most frequent with 378 uses, was predictable. But it was surprising to see power used far fewer times (111). Frequently-used terms related to people, such as citizens, are mentioned 112 times. Yet across all 99 essays, the 111 mentions of power are unevenly spread. In fact, more than half (53) do not mention it at all.

Across the 99 essays analysed, I was surprised to find the term 'power' mentioned far less frequently than 'people'

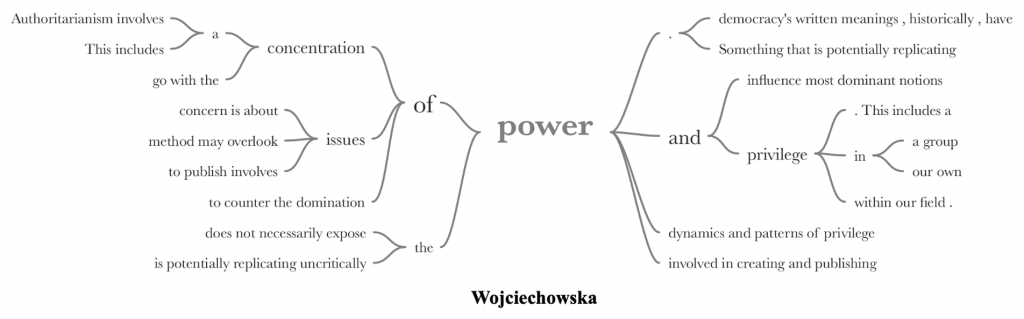

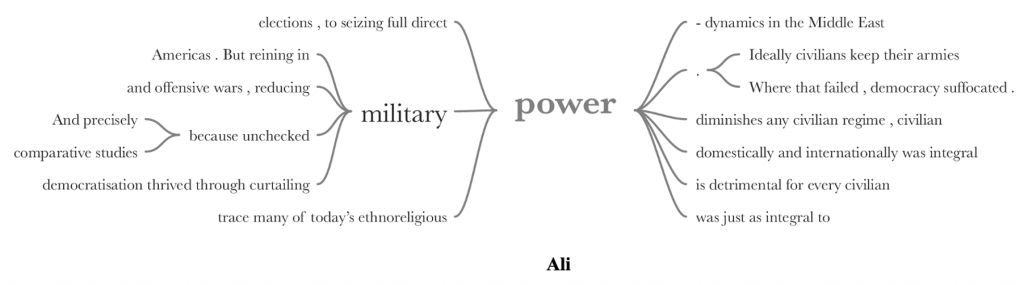

Why such asymmetry? To find out, I examined the few essays which refer frequently to power. The two which mention power most are Marta Wojciechowska’s call for a more critical, self-reflective study of democracy, and Hager Ali’s discussion of civilian control over militaries. Here, word trees show these authors' contextualisations of power:

Both essays discuss power in an appropriately cautionary manner. Is this why the word appears less often than people/citizens: because the term is loaded, even toxic? If so, we would see power mentioned more often, given the need to critically engage with it.

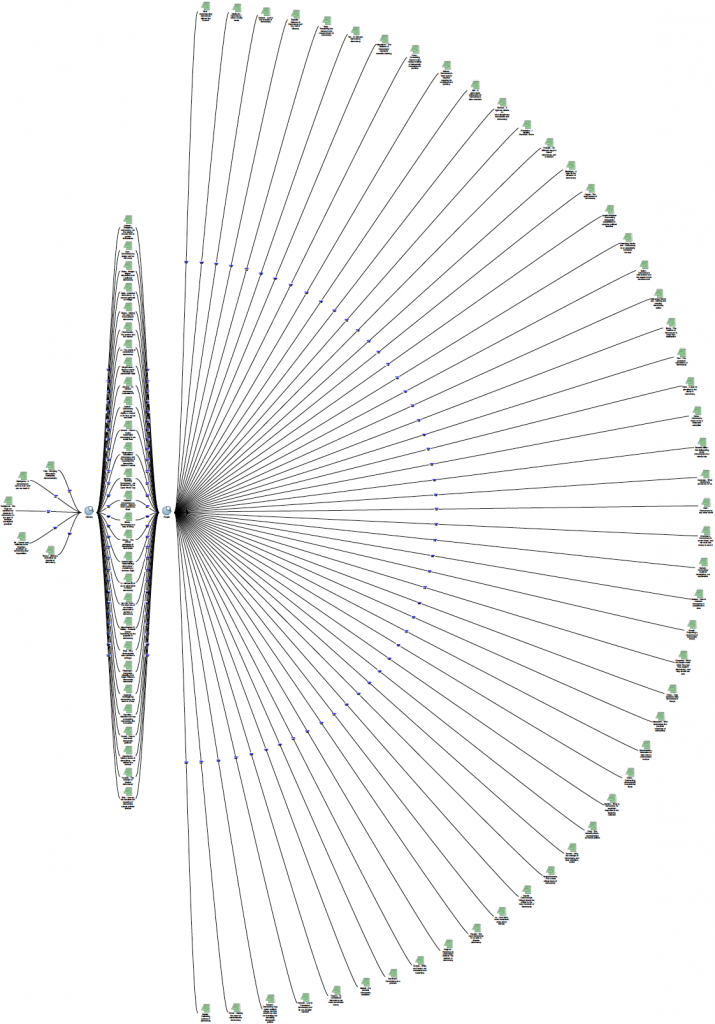

Examining the asymmetry from another angle, we see that discussions of the demos cluster around a few frequently-used terms:

This illustration shows which essays mention people and/or citizens (the two most frequent terms in relation to the demos). On the right are essays that only mention people, in the middle those mentioning people and citizens, on the left those mentioning only citizens. This supports the notion that a few key terms relevant to (though of course distinct from) one another have dominated discussions of the demos.

In pursuing this theme of ‘clustering’, consider the essays that invoke the term people most frequently. These are the entries by Yida Zhai, Li-Chia Lo, and Chih-yu Shih. All three reveal myriad terms directly relevant to power (to the extent that they stand in for this term). In Zhai’s case, relevant terms include government and ownership. For Lo, the focus is on mastery and sovereignty; for Shih, mastery, ownership and agency.

Is this simply a matter of nomenclature, or is there a deeper difference? In answering this question I recall Dahl’s musings on ‘popular rule’. Dahl, in 1967, identified fundamental conceptual issues that remain highly relevant and largely unresolved:

suppose we accept the guiding principle that the people should rule. We are immediately confronted by the question: what people? I don't mean which particular individuals among a collection of people, but rather: what constitutes an appropriate collection of people for purposes of self-rule? … are there any principles that instruct us as to how one ought to bound some particular collection of people, in order that they may rule themselves? Why this collection? Why these boundaries?

Following Dahl’s train of thought, a crucial question arises. How can we define rule, and is rule even the most appropriate term to use? I believe we face that conundrum here, concerning power.

A central focus of this series is the benefits of terminological exactitude to theory, and subsequently to practice. In better understanding a given term (e.g., democracy), we better understand the associated concept(s) in theory and practice. The essays engage critically with democracy, and to some extent with people, but not nearly as much with power.

Contributions to this series do not merely describe the democratic status quo. Rather, they discuss how to change it. Understandings of power inform not only the means of change, but the envisaged result of that change.

Contributions to The Loop's Science of Democracy series do not merely describe the democratic status quo; they discuss how to change it – and envisage the result of that change

Indeed, it is the terms of ability to effect change which defines power (Dahl stated that 'A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do'). Government; ownership; mastery; sovereignty; agency: all of these – I would argue – entail different understandings of power, i.e., the means and intended results of change.

Science of Democracy seeks short essays that engage directly, and critically, with power. This would be in keeping with the spirit of the discussions in the series so far. It would also help to address the dilemmas identified in this particular essay. In order to understand democracy, we must engage with both demos and kratos.

No.105 in a Loop thread on the Science of Democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series