Around the world, children’s rights are at risk of abuse. But are all children (or rights) equally at risk? Oliver Fiala, Elizabeth Kaletski, and K. Anne Watson argue that more extensive and disaggregated data are vital for understanding the extent to which children’s rights are realised

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) – the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history – enumerates the rights to which children are entitled. Although this global commitment to children has improved their lives on some dimensions, their rights still face systematic violations.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, but children's rights still face systematic violations

Articles 24 and 28 explicitly discuss children’s rights to nutritious food and education. However, malnutrition and barriers to schooling remain significant concerns throughout the world. As argued by Eduardo Burkle about human rights more broadly, continued work generating reliable, comparable, and disaggregated data on children is particularly critical in order to hold states accountable to their commitments under the CRC, and to understand variations in children’s experiences.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) Expert Survey compiles data on human rights for more than 40 countries, sorted on two dimensions: rights at risk and people at risk. Rights are grouped into the three broad categories of safety from the state, empowerment, and economic and social rights. Respondents communicate which groups in society are most at risk of experiencing rights violations by selecting from a list of 39 identities, including children.

Of the 13 rights covered by the People at Risk data, only one is not identified as being at risk for children in at least some countries

For 2021, respondents identified children as being at risk of experiencing rights violations in 38 of the countries surveyed. Of the 13 rights covered by the People at Risk data, only one – freedom from death penalty executions – is not identified as being at risk for children in at least some of these countries.

Perceptions of this risk vary. In Nauru, every respondent identified children’s right to food as being at risk. In Hong Kong, though, the highest proportion of respondents that identified children’s rights as being at risk was 5% (for freedom from torture and the right to expression).

These responses also focus on children in the aggregate. However, some groups of children are systematically more at risk than others. Save the Children’s GRID Child Inequality Tracker organises global data from publicly available household surveys. It identifies inequalities in outcomes for children across gender, wealth, and geography.

Combining these datasets can explain why respondents from certain countries may be more likely than others to identify children as being at risk, and highlight important nuances within rights outcomes. Two examples illustrate these insights.

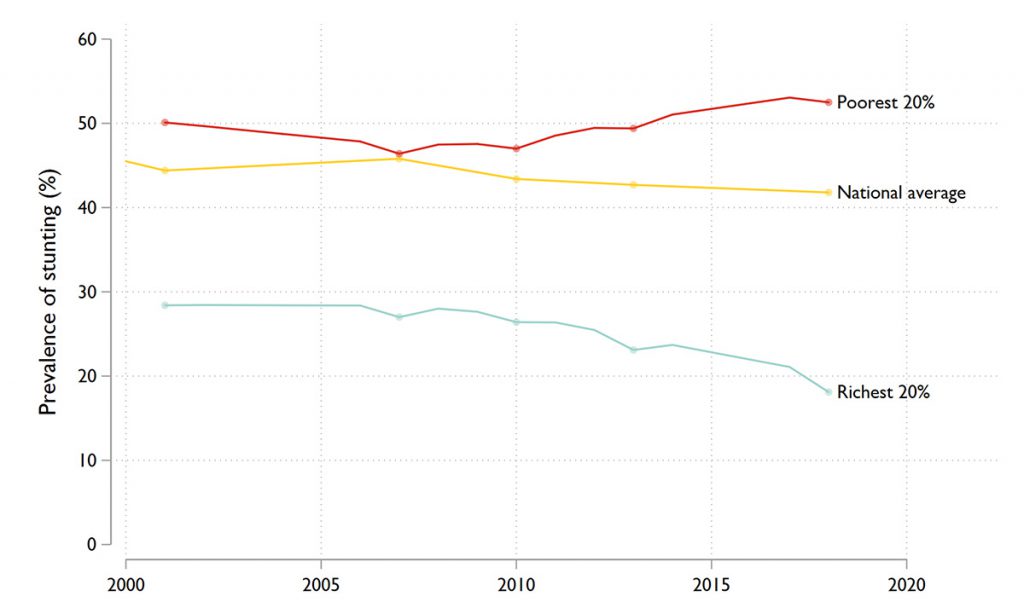

First, let’s have a look at the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In HRMI’s expert survey, 33% of respondents considered children at risk of not having adequate food. This is reflected in high deficits in nutrition – across the country, 4 out of 10 children are stunted.

Data from GRID illustrate how important it is to understand access to rights for different groups of children. For instance, in 2018, stunting rates were 53% for the poorest children in the DRC. In contrast, the figure was 18% for the richest, with gaps between the groups actually widening over the last decade.

Similarly notable gaps exist by location. While stunting rates were 29% in urban areas, they rose to 50% in rural areas, with differences increasing over time. The geographic divide is even more stark when we compare the region of Kinshasa, where only 16% of children were stunted, to Kwango, where 55% were stunted. These gaps must be taken into consideration as we develop insights about children’s right to food in the DRC and elsewhere.

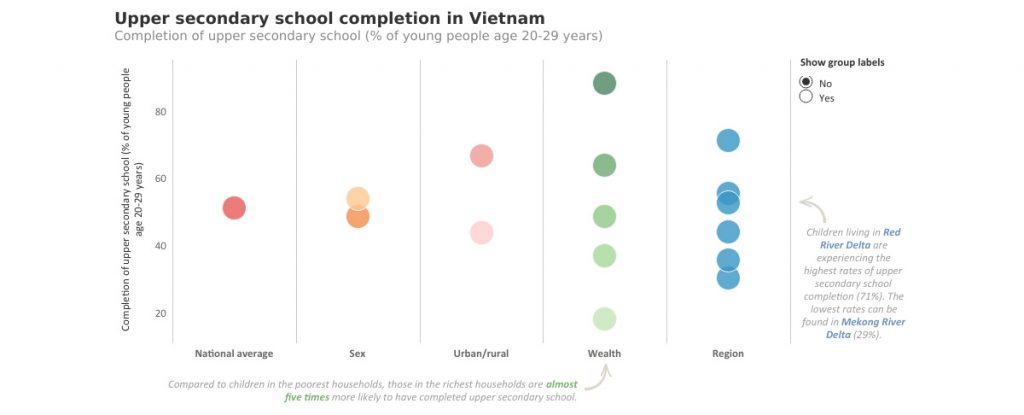

Consider a second case: children’s right to education in Vietnam. 12% of HRMI’s respondents identified this right as being at risk.

GRID identifies some gaps here, too. In 2014, only 51% of children completed upper secondary school in Vietnam. Similarly to the DRC, location matters. While 66% of urban children completed upper secondary school, only 43% of rural children did so. The wealth gap was also enormous. While 88% of children from the richest families completed upper secondary school, only 18% of children from the poorest quintile of families did the same.

HRMI’s survey also identifies children missing from the household survey data used in GRID – street children and homeless youth. 44% of HRMI respondents identified street children and homeless youth as being at risk for violations of their right to education. This was much higher than the proportion of respondents for all children, at 12%. Unfortunately, children experiencing homelessness – as well as those with disabilities, refugees, or others – are often uncounted in official data. Interpreting the datasets together thus builds a more complete picture of respect for children’s rights.

Data collection and dissemination efforts such as those by HRMI and Save the Children, discussed here, as well as others (particularly UNICEF), are vital for holding governments accountable for their obligations under the CRC. But they don’t tell the whole story. Our information about children’s rights around the world is not complete.

We have very little global, comparable data on civil and political rights for children, and struggle to distinguish the experiences of specific groups of children who may be at greater risk

In addition to needing better time and country coverage for data that already exist, we need data that are disaggregated by multiple identities. We have a great deal of information on health and education outcomes, like stunting and schooling completion rates. But we have very little global, comparable data on civil and political rights for children, like political participation or freedom of expression. And even for children’s economic and social rights, we have more data on outcomes (like those discussed here) than we do for domestic laws and programmes. This makes it much easier to describe what children’s experiences are than it is to explain them.

Widespread ratification of the CRC brought children to the forefront of international human rights conversations. Data subsequently spurred progress on the realisation of children’s rights around the world. But there remains much work to do.