Luca Verzichelli explores the crisis of democratic representation and the shrinking space for citizen-institution engagement. Launching a series on 'democratic disconnect', he calls for a new democratic pedagogy, fresh analytical tools, and innovative solutions to reconnect actors, strengthen institutions, and adapt democracy to twenty-first-century challenges – before it's too late

In his first term, Donald Trump said he wanted to ‘Make America Great Again’. Trump used his inaugural speech to claim he had a mandate to give the people back ‘their faith, their wealth, their democracy’. But can he make American democracy great again by suspending the fundamental rules of representative democracy, changing its practices; indeed, its very image?

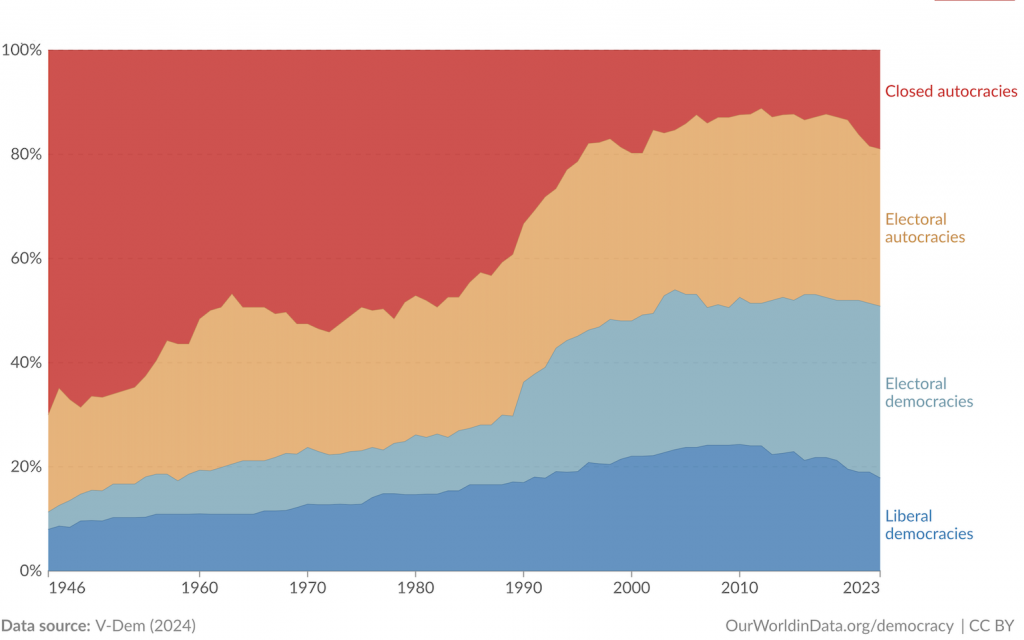

At the end of the twentieth century, democracy's future looked bright. Now, however, political commentators are beginning to question its ability to survive. We are witnessing, they argue, significant regression in the postwar model of representative democracy. In contrast with Samuel P. Huntington’s democratic golden age, current changes in representative and democratic politics – in Europe and elsewhere – show a regressive, even degenerative, tendency. A 2025 V-Dem report confirms that, since 2010, liberal democracies, in contrast with closed autocracies and electoral democracies, have steadily declined:

This representative disconnection is a multidimensional phenomenon of regression in the demos-kratos (people-power) linkage. Disconnection is not new in modern democracies. But for the first time, we may be experiencing regression in representative democracy’s institutions and practices. This raises theoretical and analytical concerns about the scale of disconnect, and the unique confluence, in our current age, of globalisation and digital revolution. It is precisely this disconnect that the REDIRECT Project's multidisciplinary research agenda aims to address.

Disconnection is not new in modern democracies. But for the first time, we may be experiencing regression in representative democracy’s institutions and practices

The process of disconnect is multidimensional. It is therefore important that we disentangle its various elements. Democratic disconnect is transforming the roles of political representatives, and of the people represented. It is transforming parliaments, parties and other representative institutions, and the informal circuits through which we articulate the demands and values of representation. Voter abstention is on the rise; democratic legitimacy in decline. Widespread disillusionment with representative politics is excluding many from the democratic process.

The power of representative institutions is under threat. Parliaments’ legislative functions have been curtailed or minimised; their reputation – and citizens' trust in them – greatly reduced.

Voter abstention is on the rise; democratic legitimacy in decline. Widespread disillusionment with representative politics is excluding many from the democratic process

Fact-checking highlights how our democratic leaders are exploiting rhetoric in the post-truth age. Donald Trump, for example, has accused the media of spreading disinformation and being the 'enemy of the people'. Judicial institutions he accuses of 'bias'. Many see Trump's attacks as 'paving the way for authoritarianism'. Political party leaders exacerbate the problem by adopting gladiatorial or opportunistic attitudes, or binary, antidemocratic, friend-versus-enemy logic.

In the past, parties’ intermediation enjoyed a social dimension. This has been eroded, with damaging consequences. And the role and power of governments – as collegial institutions managing public affairs – is diminished in purpose and relevance.

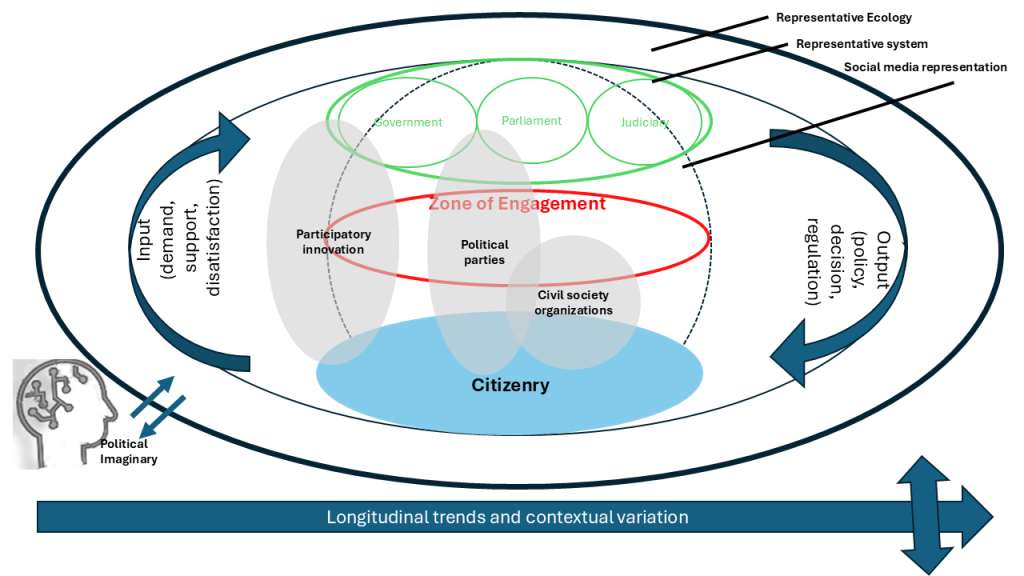

Political representation, as a method of governing and as an institutional structure, has steadily weakened. In the broader context of representative ecology, this weakening comprises institutional and informal processes of democratic representation. We must take this ecology into account. We cannot afford to study the locus of representation (where it takes place) without considering the focus (how and between whom) representation takes place, and vice versa.

A fundamental disconnect has arisen between demos and kratos. To reconnect them, political scientists must study how the three dimensions of the disconnect – individual/affective, institutional/regulative, and social/intermediary – interact.

Our analysis must go beyond the specific, familiar imperfections of democratic representation, and consider its overall functioning and quality. We need a broad perspective, analytical tools and a conceptual language that captures this mode of governing, not as an alternative to participatory, deliberative, partisan, and social forms of democracy, but as a way of incorporating them into the ecology of representation.

Does representative democracy simply need 'spare parts'? Or are we seeing an irreversible breakdown of the democratic engine?

This demands a multidisciplinary approach that reflects the spectrum of democratic possibilities. Political science must develop a new and imaginative vocabulary that facilitates engagement beyond academia. Does representative democracy simply need 'spare parts'? Or are we seeing an irreversible breakdown of the democratic engine?

A multidisciplinary approach opens new avenues for rectifying the problems facing democratic representation. As The Loop's Rescuing Democracy series suggested, we could encourage greater representation of younger generations in politics. We could improve integration between electoral moments and participatory processes. And we could redefine the role of parties beyond the mere selection of candidates for public office.

The institutions of political representation are part of a more general democratic ecology. Peter Mair would say that this ecology is retreating into the narrower zone of engagement of those political actors to whom we have traditionally delegated democratic intermediation. The shrinking of this zone of engagement between citizens and institutions has left space for other players – notably billionaire tycoons and tech barons – to disrupt the traditionally slow pace of representative democracy.

Those who study these phenomena are not generally accustomed to mix interpretation and prescription. When scholars move from analysis to problem-solving, we often end up using the same language as the political actors we criticise for their simplistic solutions.

Fixing the disconnect in democratic representation requires a leap of the imagination. We must seek new forms of analysis and solutions, new tools for reconnecting actors and institutions. There are some good practices in the current representative ecology of our democracies on which to build. These could be forms of direct democracy, ways of reducing the gap between elites and citizens, improving governability, or making deliberative processes more effective.

Political scientists need to imagine a new democratic pedagogy and create new, inclusive and participatory representative instruments for the twenty-first century, before it is too late. The conversation starts here.