When it comes to migration, the past wields considerable power over the present. Christina Zuber argues that ‘ideational legacies’ explain why outdated policies are upheld against pressing needs for change. Those wishing for reform cannot just point to what’s needed. They must reimagine what migration means for the German nation

Germany’s private and public sector are struggling to find workers. Restaurants close early, hospitals operate beyond capacity, citizens wait long hours in public agencies. It will get worse. Baby-boomers born in the 1960s are now nearing retirement. Lower birth rates in subsequent generations mean that those who are now active in the labour market can neither fill the gaps, nor keep the intergenerational pension system afloat.

An obvious solution is immigration. The director of Germany’s federal agency of labour estimates that Germany needs a net intake of 400,000 immigrants per year. Following a new labour migration law in 2019, the current coalition of social-democrats, liberals and greens is now working on a series of migration reforms. These range from lowering thresholds for entering the country to the introduction of dual citizenship.

Germany’s federal agency of labour estimates that Germany needs a net intake of 400,000 immigrants per year

These reforms, however, have come late. Germany's post-war constitution and its commitment to learn from history generated a widely-shared responsibility to protect refugees. Yet Germany lags behind other OECD countries in adopting adequate legislation and administrative procedures for migrants seeking work, not asylum.

When politics fails to respond to changing societal needs, the reason often lies in the past. The past is often kept alive through what I call 'ideational legacies'. When a government initially encounters a given policy problem, the democratic contest of ideas for how to think about the problem is often quite open.

Over time, however, political elites often manage to build consensus around a particular solution and rhetorically connect this solution to the very definition of national identity. If they succeed, this consensus can outlive even profound changes in the constellation of interests. Rather than debating 'what we need', political elites cling to solutions they perceive as connected to 'who we are'. Think of gun rights in the US, or the absence of speed control on German motorways.

Political elites attract support for solutions connected to 'who we are' rather than 'what we need'. Think of gun rights in the US, or the absence of speed limits on German Autobahns

We can find ideational legacies in many policy areas, but particularly in migration and citizenship. This is because the question of 'who can join' is inherently connected to definitions of 'who we are'. Cross-national research shows a striking stability of policies regulating migrant integration and the acquisition of citizenship. Historical junctures at which societies originally defined what migration means for their collective identity help explain such stability.

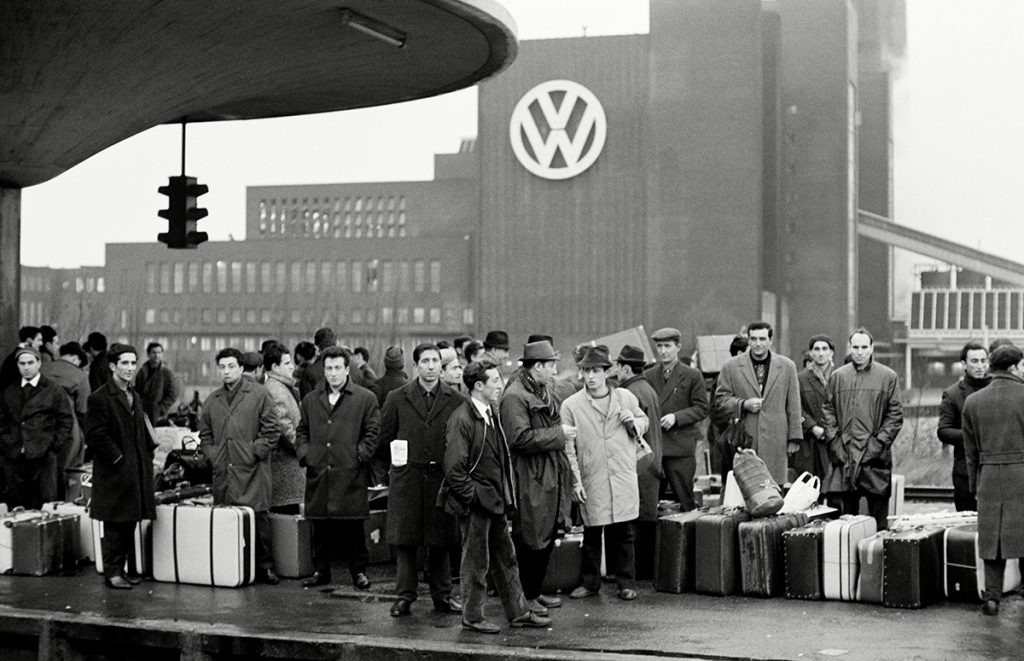

The historical juncture defining ideas about migration for post-war Germany consisted of a series of bilateral agreements that West Germany concluded with Italy, Spain, Greece, Turkey, Morocco, Portugal, Tunisia and Yugoslavia between 1955 and 1968. Under these agreements, West Germany received so-called Gastarbeiter, or guest workers; the German Democratic Republic also made similar agreements. The German economy, then as now, was in dire need of workers. The dominant idea was one of temporary stays; it eschewed discussions about inclusion and permanent settlement.

Reducing the politics of migration to the idea of 'guest workers' resonated, because it tapped into even older ideas of the German nation as an ethnic nation. It was a concept that did not foresee ethnic others joining the club. Before its eventual reform in 2000, German citizenship law saw descent from Germans as the default. It treated the naturalisation of people without German ancestry as the exception.

The ideational legacy of the guest-worker experience was to negate any connection between immigration and German identity. In parliamentary debates between the 1960s and the 1980s, the phrase 'country of immigration' was used either to refer to other countries, or to explain why it did not apply to Germany. In 1983, the liberal-conservative coalition treaty even included the phrase 'The Federal Republic of Germany is not a country of immigration'. Most of Germany's political elites have, since the 1990s, increasingly accepted the realities of migration. Yet the country’s major centre-right party, along with many German citizens, still cling to it.

Ideational legacies are made by political elites. They can also be unmade. But the task is considerably harder. The more often ideas about how to think of a certain problem are repeated, and the more closely they become connected to collective identity, the more convincing they become. Recognising that societal needs have changed is a beginning. But it is not enough.

A quarter of Germany's population now has at least one parent born abroad. Any claim that immigration is alien to Germany thus faces empirical negation

Proposals to reform migration, integration and citizenship laws cannot simply point to changing labour markets and demography. They have to work on reimagining national identity itself. Though challenging, this is possible because the repertoire of societal dispositions (collective identities and values) is neither completely homogenous, nor fixed. In addition, by changing the composition of society, migration itself changes this repertoire. A quarter of Germany's population now has at least one parent born abroad. Any claim that immigration is alien to Germany thus faces empirical negation.

Incidentally, the very same historical juncture of the arrival of guest workers could also lend itself to constructing a different ideational legacy: that people of diverse ancestry and culture worked together to build Germany after the war. It was perhaps in this vein that the current German government explicitly valued the achievements of guest workers in the coalition treaty. Reimagining early migration as integral to making Germany the country it is today could be one way of reconciling ideas of 'who we are' with 'what we need'.