Zsófia Papp and Godfred Bonnah Nkansah show that during Covid-19, Hungarians judged the quality of democracy less by procedural norms and more by government performance. Their findings reveal when citizens in backsliding regimes accept violations of democratic standards – and when they refuse to compromise

During the Covid-19 pandemic, governments everywhere restricted civil liberties and concentrated power in the executive. Administrations often justified these steps as necessary for rapid crisis response. But how did citizens judge the democratic quality of such emergency governance?

Our research shows that performance mattered more than procedure. Hungarians evaluated democracy primarily through the lens of public health outcomes and economic performance. If infections fell or the economy improved, respondents viewed a country as more democratic – even when it violated key democratic norms. But some freedoms remained non-negotiable.

This pattern offers a warning for democracies under strain: people may tolerate procedural erosion when outcomes look good, especially in backsliding contexts where democratic baselines are already weakened.

We used a conjoint experiment with 1,000 respondents to test how people judged democratic quality under different emergency scenarios. Each scenario varied the measures affecting elections, parliamentary powers, civil liberties, and crisis performance.

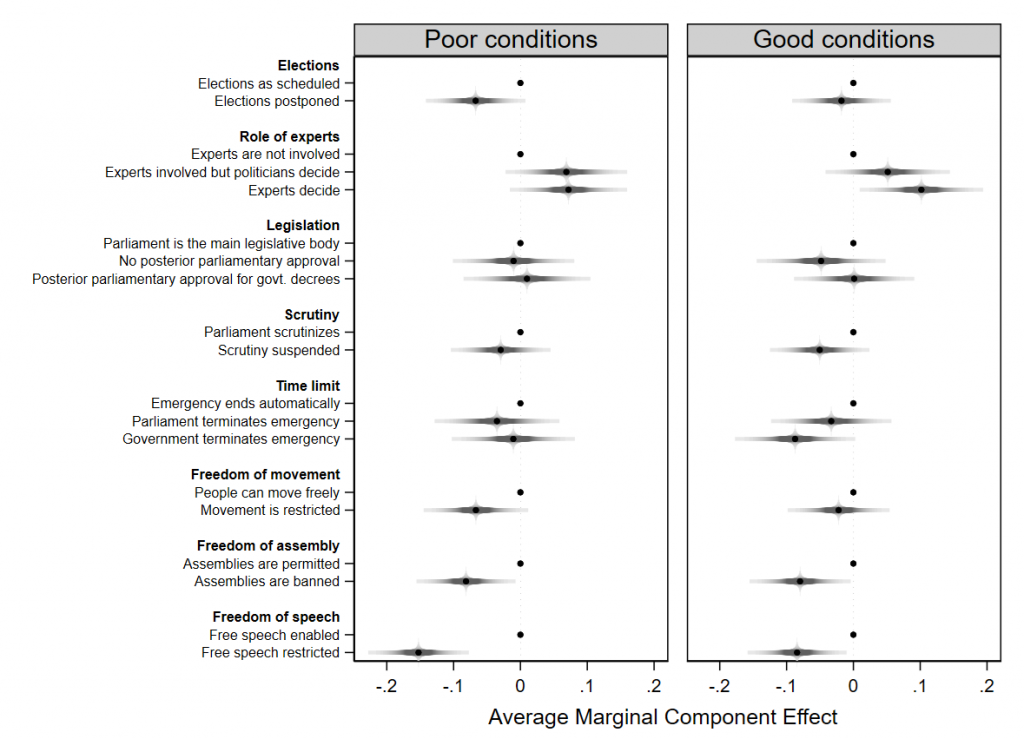

Despite Hungary’s ongoing democratic backsliding, citizens still held clear expectations. Respondents consistently preferred scenarios in which elections were held on time, because postponements reduced the perceived quality of democracy. They also favoured arrangements in which experts played a central role, even accepting that technocratic actors could temporarily replace elected officials. They valued parliamentary involvement in law-making or, at minimum, the legislature’s approval of government decrees after the fact. Above all, they insisted that freedoms of speech and assembly remained untouched, treating these rights as essential pillars of democratic governance.

Our survey found that Hungarians' willingness to tolerate emergency measures was conditional. When death rates fell or the economy grew, tolerance for violations increased

Yet these preferences were conditional. When death rates fell or the economy grew, tolerance for violations increased.

Two findings illustrate these trade-offs most clearly. Hungarians normally view postponing elections as undemocratic. However, when scenarios depicted falling death rates and economic growth, resistance to delaying elections softened. In good times, safeguarding public health and prosperity made such postponement more acceptable.

A similar pattern appears for freedom of movement: although citizens generally saw curfews and travel limits as harmful to democracy, respondents were willing to accept these restrictions when they came with substantial economic gains. By contrast, freedoms of speech and assembly remained 'red lines', defended even under the most favourable conditions of falling death rates and economic prosperity. These results reveal a hierarchy of democratic values, in which some liberties become negotiable during crises when material benefits compensate, while others remain firmly untouchable.

Hungarians showed striking support for expert-led decision-making. They preferred scenarios in which public health specialists shaped emergency policy, even if elected politicians had little say. This technocratic preference held under good and bad conditions.

Even if people accept concentrated power at the height of an emergency, they expect executive restraint once a crisis has stabilised

Parliamentary powers, however, elicited more ambivalence. Respondents valued legislative involvement, but under severe crisis – especially rising death rates – they tolerated executive dominance. Only when conditions improved did they again reward profiles in which parliament reclaimed an active role.

Interestingly, citizens demanded a sunset clause – a clear end to emergency powers – only when economic and health conditions were strong. This suggests that people expect executive restraint once a crisis stabilises, even if they accept concentrated power at the height of the emergency.

Hungary, long identified as a case of democratic erosion, offers a hard test for theories of democratic resilience. If citizens in such a context still distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate emergency measures, this suggests enduring democratic expectations.

Yet the results also highlight the danger of performance-based legitimacy. When citizens prioritise outcomes over norms, governments gain incentives to justify procedural shortcuts as 'effective governance'. Emergency powers then risk becoming tools for further autocratic consolidation, especially if crises are prolonged or manufactured.

Crucially, however, our research also shows that tolerance is conditional and reversible. Once the immediate threat recedes, people recalibrate their expectations and once again value democratic checks. Democratic backsliding may thus be more cyclical and crisis-dependent than linear.

Citizens' tolerance for emergency measures is conditional and reversible. Once the immediate threat recedes, people recalibrate their expectations

As Luca Verzichelli argued in this series' foundational piece, democratic disconnect emerges from a weakening link between citizens and representative institutions. Our findings show that crises make the gap between citizens and their institutions even wider. When people focus only on government results, they sometimes overlook violations of democratic rules. Still, citizens do protect some essential freedoms, and these could indeed help restore democracy after the crisis ends.

Emergencies always test democracies. Our study reveals that citizens do not abandon democratic ideals under pressure, but they do reorder them. They accept delays, shortcuts, and restrictions when survival and economic stability are at stake. But they also defend core freedoms, especially speech and assembly, regardless of performance.

The lesson for policymakers is simple: crisis management cannot rely on performance alone. Citizens expect results, but not at the cost of democratic integrity. When the next emergency hits – whether it is health-related, economic, or environmental – governments must balance swift action with visible respect for democratic norms.

Democracy can bend during a crisis. But it should not break.