The pandemic has led to an increase in experts' authority – yet substantial contestation of their expertise, write Mirko Heinzel and Andrea Liese. This polarisation poses a risk for proper public deliberation and the fight against Covid

During times of uncertainty, experts can bring some comfort. When crises hit, we instinctively look to those who can convince us things will get better soon.

Experts reassure people that they are in good hands, and managing the situation. That's why we rely on them to guide us through major societal crises.

Such reliance has been on full display during the Covid-19 pandemic, during which experts have been catapulted into the public spotlight. Statements by public health institutions make headline news, health researchers from reputable universities become daily guests on primetime TV shows, and the news media tracks the World Health Organisation’s every move.

While many media outlets and governments rely extensively on experts, their authority has not gone uncontested. Experts’ authority has become a major political cleavage — separating those who argue that one should 'follow the science' and those who question scientists' authority.

Such intense public scrutiny means that experts have also paid personal costs. Many have experienced personal attacks, and even received death threats on social media. Examples include the #FireFauci activism to discredit US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony Fauci, and the smear campaigns and threats against German Covid-19 expert Professor Christian Drosten.

Many experts have experienced personal attacks, and even received death threats on social media

Beyond the impact on experts themselves, uncertainty around the crisis has induced some citizens to listen to conspiracy theorists. For example, anti-vaxxers and others with fringe views have pervaded anti-lockdown protests all over the world. These groups have repeatedly discredited public health experts and called for their removal. Anti-science protesters are, at least in part, the drivers behind many such demonstrations.

All this points to a sobering conclusion: societies appear polarised in their opinions on experts. While some have relied on experts during the pandemic, others have questioned experts' knowledge and legitimacy.

How does such polarisation influence experts' ability to advise citizens during the pandemic? Polls generally show substantial public trust in experts. A recent Wellcome Trust poll in 140 countries finds that 72% of the global public trust scientists. But a sizeable minority is more sceptical towards their expertise.

Can such scepticism affect the extent to which public sector experts influence support for policy measures to combat Covid? Our research aims to unpack this.

72% of the global public trust scientists

During May 2020, we conducted a survey experiment in Germany and the UK, to better understand how experts affect citizens' attitudes towards lockdown measures. In our experiment, we asked people how they felt about Covid-19 lockdowns, varying the source of the endorsement between different public sector organisations.

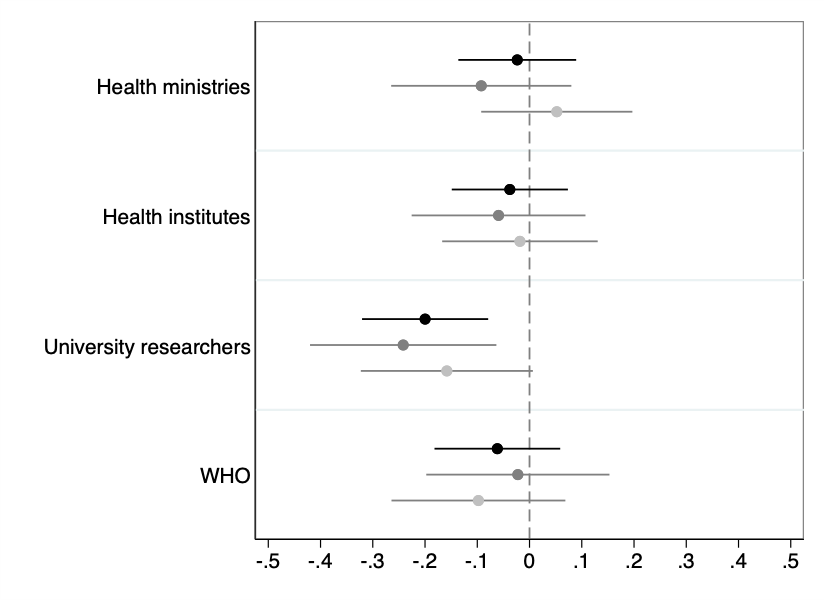

On average, these organisations' endorsements did not influence citizen support for lockdown measures — see Figure 1. The results are surprising: if anything, there is a small negative effect for university researchers at reputable research institutions.

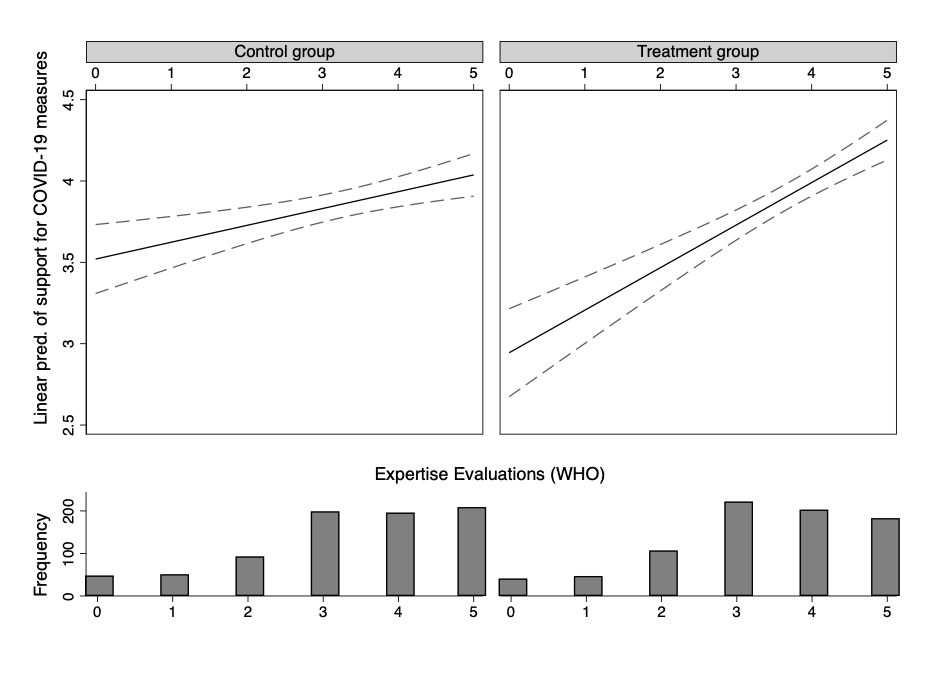

However, we also find that these averages seem to mask considerable polarisation — see Figure 2. The 25% of respondents most convinced of public sector organisations’ expertise become more supportive of measures when that organisation endorses them. But the 25% of respondents most sceptical of their expertise are dissuaded by discovering the source.

Interestingly, we do not find a similar pattern regarding biased experts. Whether or not respondents believe a source is impartial does not seem to affect its authority. This finding is unexpected given the charges of bias in the Covid-19 debate.

Notable examples are alleged biases towards the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the pharmaceutical industry, or particular countries, such as China.

The increasing reliance on experts during the pandemic has spurred a normative debate on evaluating scientific rule and the public’s blind obedience on ethical grounds. The discussion reveals a fundamental dilemma. Blind obedience to authority, of experts or otherwise, can be harmful to democratic deliberations. But uncertainty during a pandemic requires the public and politicians to rely on other people’s expert authority to enable a comprehensive response.

Whatever one’s position on this dilemma, expert-induced polarisation would be a worrying development. If people become less convinced of something just because someone recommended it, they're not taking part in a deliberative exercise, either. Instead, they disobey blindly, regardless of the merits of the argument.

Expertise-based polarisation could endanger informed public deliberations and the effective fight against the pandemic.