Our response to political manifestos during elections usually reflects the different ways we think about politics. Yet, we can also demonstrate our politics in less obvious stereotypical associations, including consumption and lifestyle choices, argue Gaetano Scaduto and Fedra Negri, through an experiment they conducted on food in Italy

Liberals drink lattes, conservatives drink black coffee. Right-wingers eat meat and leftists prefer vegetables. Socialists love an IPA, while their opponents prefer to crack open a lager.

Political stereotypes related to lifestyle choices – particularly food and drink preferences – have inspired academic research, journalistic accounts, and even political ads in the US:

Yet, no one has considered whether these stereotypes also exist and are consequential in Europe…until now. We have researched this question in one of the most food-obsessed countries in the world: Italy.

In Italy, citizens have made lifestyle choices based on the crises of parties and major ideologies of the 20th century, the decline of class-based voting, and the emergence of voter individualisation. What Italians eat, how they dress, and the car they drive are all substantial indicators of Italians' political preferences. Research published in 2015, for example, found that Italians' consumption choices predicted voting choices more accurately than social class.

Research has shown that Italians' consumption choices predict voting choices more accurately than social class

Consumption choices and political preferences, combined with media portrayal, and the behaviour of politicians, can all generate associations and stereotypes that we can use to estimate citizens' political orientation, as this famous 'Can you tell a Trump fridge from a Biden fridge?' quiz from The New York Times exemplifies.

But how widespread is this way of thinking about politics in Italy? And does it have consequences for the way Italians interact with each other?

Our research is based on a survey experiment with 1,100 respondents. We asked them to imagine they were in a restaurant and to choose from these five set menus, all of which were the same price. Respondents were told that the person at the next table ordered a particular, randomly assigned menu.

We then asked respondents, if they were willing, to guess the political ideology and the party for whom the person sitting at the next table voted, based on the menu they chose. 56% of respondents dared to take a guess. The remaining 44% responded that knowing what a person eats is not enough to guess how they vote, and abstained from doing so.

56% of respondents said they would be willing to guess the political ideology of a person based on the menu they chose

But what political expectations did the food choices generate?

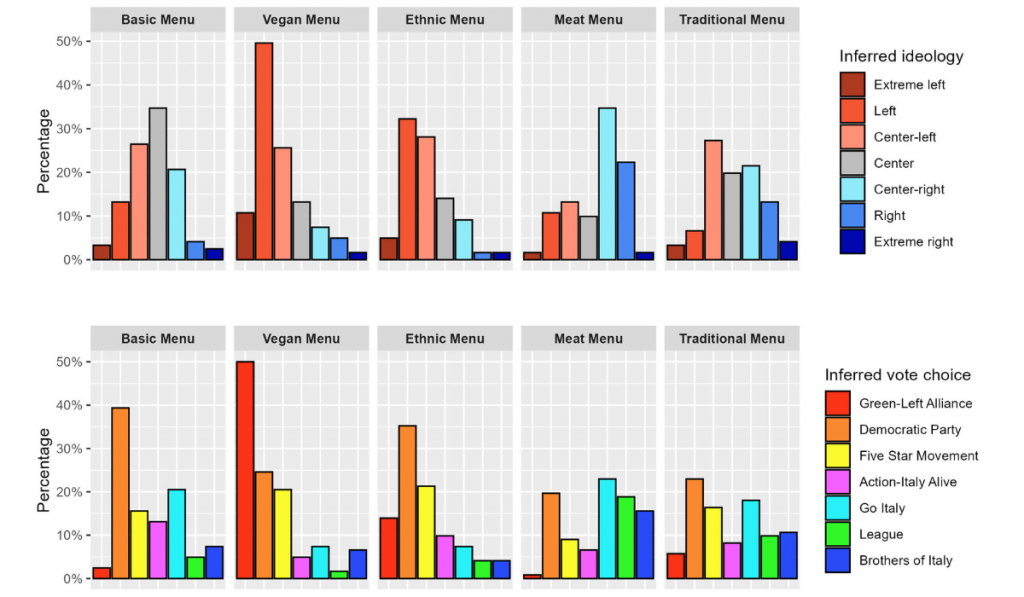

As the figure below shows, respondents weakly associated the basic menu with centrist preferences. The party most associated with this option is the Democratic Party (S&D). Respondents strongly associated the vegan menu with leftists and the Greens-Left Alliance (GUE/NGL). Respondents also associated the ethnic menu with leftists, but with the Democratic Party. They associated the meat menu with the centre-right. Finally, the traditional menu shows no particular association: the love for typical Italian cuisine apparently transcends ideologies.

We then asked respondents to provide reasons for their answers. Many were based on character traits that would signal both political and food preferences. For example, one respondent suggested vegans are left-wingers because they 'do token things, just to give themselves an attitude'. On the other hand, a carnivore is deemed a right-winger because they 'enjoy life and the pleasures of the table, as in Berlusconi’s golden age'. The full set of open-ended responses, in Italian and as provided by the respondents, is available here.

Finally, we asked respondents whether they would be willing to have coffee and talk about politics with the character described. Responses to this question support media narratives about increasing polarisation. When the respondent expects the character to belong to the same political party as them, they are more likely to interact; otherwise, the propensity to engage in conversation drops by more than 20%.

So, our research shows that we can indeed infer political leanings from a person's consumption and lifestyle choices. Politicians can exploit these associations, flaunting choices consistent with their political stance, to show that they are 'genuinely' right-wing or left-wing. Take, for example, the post on X from Italian conservative MP Alessia Ambrosi, which has racked up 1.4 million views, in which she claims that right-wingers love good food and Italian wine, while left-wingers love insect flour.

Politicians flaunt consumption and lifestyle choices consistent with their political stance, to show that they are 'genuinely' right-wing or left-wing

We focused our research on food, a cultural dimension particularly important in Italy. Research does not currently exist on whether other lifestyle aspects, such as the car we drive, or the TV shows we watch, could also predict political behaviour in the same way as social class. We would be interested to see whether comparable results would show in other European countries, too.

In the meantime, we should all pay attention to what we are ordering in a restaurant. The choices we make reveal a lot more about us than we might imagine.