In the EU's most homophobic country, Poznań stands out as a beacon of queer acceptance and activism. Polish native Tomasz Gola explores the ways this city has become queer-friendly, highlighting the role of local NGOs, cultural receptivity, and proactive governance in its transformation

For the LGBTQ+ community, queer spaces meet a mutitude of needs. Such spaces are 'the cultural centers of LGBTQ+ life and often provide the formative physical space for organizing in the ongoing fight in support of equality'. Of course, queer spaces are important for facilitating free expression in already-tolerant contexts. But in homophobic societies, they become even more crucial.

Poznań, a city in northwest Poland, is an interesting case. In that city, LGBT activists and organisations have successfully established an open and accepting space in the EU’s most homophobic country. We can learn some important lessons from this queer-friendly city.

Firstly, Poznań's LGBTQ+ community is highly visible. The city's cultural institutions, NGOs and social venues all prominently represent gay life. Local authorities are receptive to the needs of the community; for example, by including them in the new education strategy for 2030. But the work of NGOs and activists would be futile if it wasn’t for Poznanians’ cultural receptivity and openness. Locals say their mindset is influenced by geographical and mental closeness to Germany, and by a respect for personal privacy.

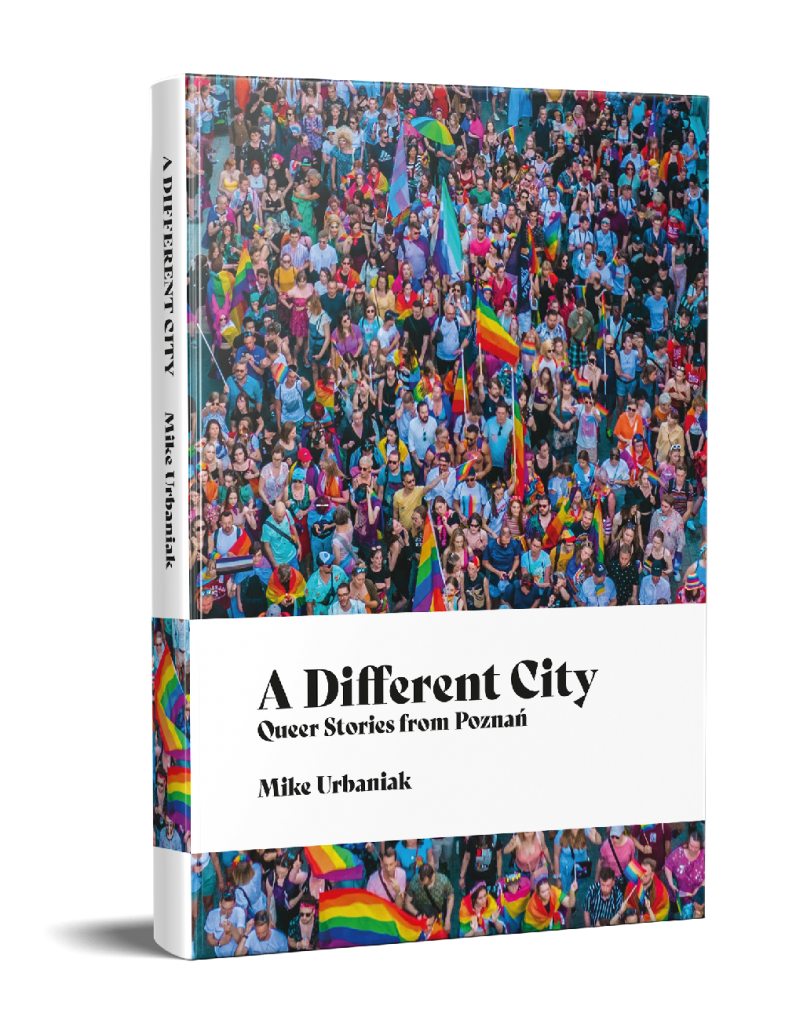

My research analysed interviews with queer-identifying individuals featured in Mike Urbaniak’s A Different City: Queer Stories from Poznan (Inny Poznań: Rozmowy z Osobami LGBT+). Interviewees revealed Poznań's strong cultural receptivity, and prominent LGBT activism.

The queer-friendly Poznań of today is the result of the city's rapid accommodation of its LGBT community. Interviewees spoke about the multiple ways their experiences of queer life in Poznań differs from that of queer friends in other Polish cities. Responses tended to focus on three areas that contribute most to the city's queer-friendly feel: venues, visibility, and support.

Soon after the democratic transition of 1989, a gay scene began to emerge in Poznań, with the opening of several queer bars and clubs. However, many LGBT-identifying Poznanians link the real blossoming of queer spaces with the founding of Grupa Stonewall (Stonewall Group), an NGO which advocates for gay rights and supports queer individuals. Stonewall opened a bookshop; a bar, Lokum Stonewall; and a nightclub, Duże Lokum.

As an interviewee who has lived in the city for about ten years enthused: 'No other city [in Poland], including my native Warsaw, has such well-developed and high-quality LGBT+ infrastructure'. Jurij, an interviewee from Ukraine, said: 'I came out of the closet and became a part of the LGBT+ community. […] I found Europe in Poznań'.

In Poland as a whole, homophobia still runs high, so LGBT people cannot take their safety for granted

Poznań's vibrant gay scene allows queer people to feel safe to express themselves freely. In Poland as a whole, homophobia still runs high, so LGBT people cannot take their safety for granted. As one interviewee told Urbaniak: 'Nothing bad has ever happened to me here because I am gay, which in our country seems like a great achievement, if not luck'.

Local activism gives Poznań's LGBT community genuine visibility, and allows them to express their identities free from discrimination. Most interviewees, employed in a wide variety of jobs, emphasised how they enjoyed fully 'out' lives, and they reported few instances of homophobic behaviour from others. A lesbian couple, both nurses, told Urbaniak: 'We are out also at work. Us being together is completely normal for our colleagues'.

Most LGBT people in Poznań live fully 'out' lives, and report few instances of homophobia

But apart from their everyday visibility, LGBT-identifying individuals are also an integral part of the city: in arts institutions, positions of authority and in local administration. One openly gay interviewee, Maciej Nowak, is the artistic director of Poznań’s Teatr Polski (Polish Theatre). During his tenure, the theatre has produced several plays with queer themes, such as those by art collectives pozqueer and Kolektyw 1A, which established queer visibility in the city's arts scene. In his interview with Urbaniak, Nowak emphasised the openness of Poznań's local authority, famously exemplified by mayor Jacek Jaśkowiak’s participation in the city's 2015 Equality March.

LGBT people in Poznań can also access an array of support services. Grupa Stonewall, for example, runs a sexual health clinic, and offers psychological help and legal advice on gender affirmation.

Multiple other organisations offer various forms of support. Fundacja Tęczowe Rodziny (Rainbow Families Foundation), for example, supports non-heteronormative families, especially those raising children. Through cooperation with local authorities, the foundation gave queer families access to the Big Family Poznań Card discount scheme.

Poznań has earned a national reputation for queer inclusion, with authorities co-funding many services, including one for queer individuals facing homelessness

In further evidence of Poznań's difference from other Polish cities, LGBT people have also been included in the 2030 education strategy planning. Poznań has now earned a national reputation for queer inclusion, with authorities co-funding many services, including one for queer individuals facing homelessness. City authorities now also officially partner in Poznań Pride Week.

Interviewees pointed to several factors for Poznań’s high cultural receptivity, including proximity to Berlin and the corresponding Western orientation. 'The closeness of Germany has always been radiating culturally and socially to Poznań', said one. This has resulted in ‘mental Germanness’ and suggests that the locals perceive themselves as different from other Poles. Poznanians respect others’ privacy: they regard non-heteronormative sexuality as a personal matter, and believe that queer presence in public space enriches diversity.

While the effect of LGBT activism in Poznań is evident, scholars predict ‘downstream effects’ of higher visibility in other places. Research found that even in less culturally receptive communities, change eventually happens through diffusion. Perhaps with the recent change of government, we Poles can allow ourselves to be a bit more optimistic. In the future, I hope to see similar accommodation in other Polish cities.