Liron Lavi and Clareta Treger argue that citizens hold a multi-dimensional perception of political representation. Using Israel as a case study, they find that citizens feel represented on dimensions that are not important to them, and that this deficit reflects their satisfaction with democracy

In Europe and around the world, democracy is backsliding as citizens’ trust in elected representatives and institutions wanes. Citizens’ preferences, perceptions, and expectations of political representation can increase voter turnout, improve trust in parliament, and satisfaction with democracy. Given that representation is a key democratic principle, how do citizens perceive their political representation? What is important to them in terms of representation?

In our recent research with Naama Rivlin-Angert, Tamir Sheafer, Israel Waismel-Manor, Shaul Shenhav, Liran Harsgor, and Michal Shamir, we break down representation in the eye of the citizens into four dimensions, introduced by Hannah Pitkin: substantive, formalistic, descriptive, and symbolic.

Our study looks at the representation perceptions of Israelis ahead of the April 2019 national election. This was the first in the series of five elections within three and a half years, and took place before the political instability, judicial crisis, and Israel-Hamas war.

We find that citizens hold a multi-dimensional perception of representation, and that some dimensions are more important to them than others. But these are not the dimensions on which they feel represented. Crucially, these perceptions relate to their attitudes toward democracy.

Most citizens (76%) view the formalistic and substantive as the most important dimensions of representation. The first pertains to rules that govern the workings of representative democracy; the second to representation of the public’s policy preferences and interests. The other two dimensions lag significantly behind. These are descriptive representation, which pertains to the resemblance between citizens and their representatives by various social categories; and symbolic representation, which is closely associated with issues of identity.

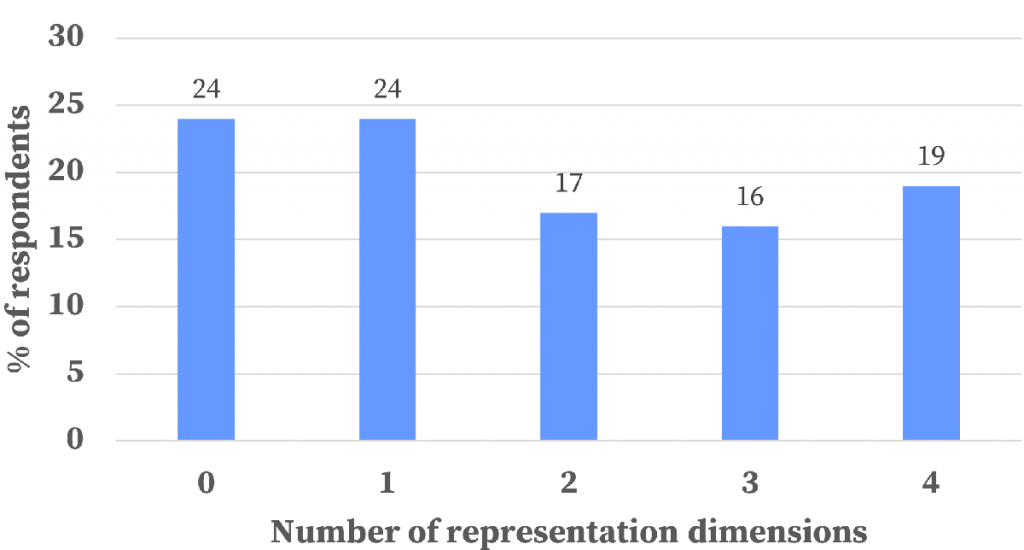

24% of voters did not feel represented on any dimension by the Israeli parliament

When we asked voters on how many of these dimensions they felt represented, we received diverse responses. A significant 24% did not feel represented on any dimension by the Knesset (Israeli parliament). The same proportion, 24%, feel represented on only a single dimension. Far fewer voters feel that the Knesset represents them on multiple dimensions: only 17% feel represented on two dimensions, 16% on three dimensions, and 19% on all four dimensions.

The demand for representation is poorly met – citizens feel represented on dimensions that are not important to them. The discrepancy is especially prominent when it comes to descriptive representation. On this metric, voters feel fairly represented, but this type of representation is not particularly important to them.

The demand for representation is poorly met – citizens feel represented on dimensions that are not important to them

Previous studies, as well as normative theories, have suggested that descriptive representation, especially by institutions, is germane to substantive representation. Our findings challenge this linkage.

Crucially, the findings indicate that citizens perceive substantive and formalistic representation to be in deficit. In other words, citizens feel that their policy positions and interests are not well represented, and they do not believe that their representatives use the authority bestowed on them in a responsible manner.

There is another question that interests us. What matters more for citizens’ overall representation perceptions and their democratic attitudes? Is it a multidimensional sense of representation, or feeling represented on one’s most important dimension?

Citizens’ sense of representation on the dimension most important to them and their sense of representation on multiple dimensions contribute to their overall sense of representation. However, the contribution of citizens’ multidimensional representation is significantly higher.

Voters who feel more represented are more satisfied with the way democracy works, and with the political system

Unsurprisingly, a sense of being represented also relates positively to support for democracy. Our results show that voters who feel more represented – especially on multiple dimensions – are more satisfied with the way democracy works, and with the political system. They also have higher trust in political institutions. We would expect this, given that representation is a pillar of representative democracy.

Despite the prominence of personalist politics and the low public trust in representative institutions, we find that it is citizens’ perception of representation by the parliament (rather than representation by a politician or a party) that matters for their attitudes toward democracy. However, this is also the type of representation that we find to be most lacking.

With the Israel-Hamas war raging, much international criticism is currently directed at the Israeli government and public. But how representative is the Israeli government of Israelis’ true positions and preferences? The weekly mass protests, the low levels of public trust in government, and mounting calls for an early election offer powerful evidence of citizens' anger and frustration.

In light of this, it is paramount to better understand how citizens perceive representation and the degree to which they feel politically represented, especially on the dimensions most important to citizens: policies and accountability.