Millions of people no longer live in their countries of birth, and this can distort political representation, argues Ekaterina Rashkova. If expats had been eligible to vote in recent Dutch parliamentary elections, we would have seen more support for innovative parties such as the D66 and Groen Links

The traditional way of understanding representation is within national boundaries. Political parties develop and propose political agendas; eligible voters get to vote and choose who should govern. Government is formed on the basis of the people’s vote and starts work on governing the country – ideally, in the direction chosen by the majority of people.

Critical to the concept of representation is the act of voting. Eligibility to cast a vote in national elections is still intrinsically linked to age (over 18 in most countries) and citizenship.

The citizenship rule applies even if one lives abroad. Some countries, however, set a limit on the number of years that citizens living abroad can vote back home.

UN immigration data reports that more than 270 million people worldwide live in a country other than the one in which they were born. So who represents these people?

Rainer Bauböck's research points to a world trend of expanding electoral rights to non-resident citizens. He questions the link between electoral rights and citizenship in light of migration. My own work shows that there has been little research on the effect of the mass movement of people around the world on the character and activity of national political parties.

270 million people worldwide live in a country other than the one in which they were born. So who represents these people?

Previous research of mine along with my work with Sam van der Staak includes special journal issues on ‘the party abroad’. Scholars provide evidence from around the world on the extent to which national parties are engaging with their voters in other countries.

They identify the type of electoral system as one of the key determinants. Other factors that influence how national parties target their diaspora abroad are the geographical distribution of the diaspora, the ease with which diaspora members can vote, and the behaviour of other parties.

Research on the involvement of national political parties abroad is emergent. Thus far, however, we know almost nothing about representation of those who no longer reside in their country of birth. This is important, especially for countries who are net-receivers of people.

The Netherlands, for example, has a population of about 17.5 million people, nearly 1.2 million of whom are non-citizens.

The 10-question online survey on the 2021 Dutch general election, which I conducted, asked expats about their political preferences and behaviour. I distributed it via Facebook expat groups in Utrecht, the Hague and Amsterdam, making it accessible the day before and the day of the national election.

My findings, based on 170+ responses, suggest that Dutch politicians must pay more attention to expats' political preferences, for three distinct reasons.

The first is that expats in the Netherlands are a large group. CBS data from 2020 reports around a million non-citizen residents of voting age.

Expats largely support innovative parties such as Groen Links and D66

Secondly, they are (ready to be) politically active. Little mobilisation is necessary for a large number of extra votes.

Finally, their participation will change the status quo. Expats largely support innovative parties such as Groen Links and D66. They also support parties with proven stability in dire situations, such as VVD1. When asked who they would vote for, expats overwhelmingly support Groen Links and D66.

Figure 1 shows distribution of expat preferences. VVD comes only third, and there is notable support for new parties Blij 1 and Volt:

Demographic questions reveal that the majority surveyed are EU citizens resident in the Netherlands for five years or more.

Voter rights in national elections for EU citizens is a subject that has already been raised in Brussels. So far, it has not led to any unified action in member states. This could be important if we consider that EU freedom of movement, work and living needs to incorporate ‘moving with his/her rights intact’.

In any case, the right to be represented is a fundamental human right.

The Netherlands allows people resident in the country for at least five years to request Dutch nationality. This naturalisation process then allows a person to vote in national elections.

But naturalisation comes at the cost of renouncing one’s original citizenship. Spouses of Dutch nationals, however, may hold dual citizenship.

about 78% of expats would vote in national elections if they had the right to do so

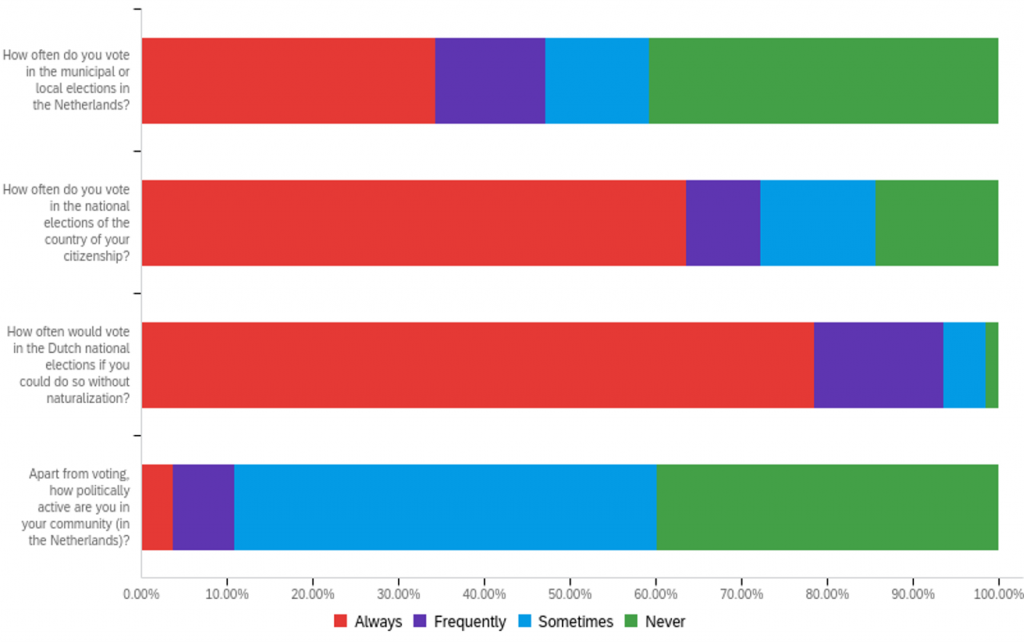

Data reveals that about 78% of expats would vote in national elections if they had the right to do so. It also reveals that they are less likely to vote in their country of origin:

This equates to over 400,000 additional votes. For the 2021 election, it means that Groen Links and D66 would have received an additional two and one seats, respectively.

These two parties together would have had more seats than the leading VVD. We can argue, therefore, that those 400,000 votes would have affected the current cabinet negotiations significantly.

Such a difference, while not large, can be important. It can lead to a stronger emphasis on some policies over others – and even to influencing the choice of Prime Minister.

This blog was updated on Monday 14 June 2021 to clarify the author's reference to Rainer Bauböck's research on electoral rights in relation to citizenship.

I am puzzled why the author of this blog attributes to me the view that "that voting should be linked to residency, not citizenship". In the article that is linked to this text and in a number of later publications I have demonstrated that there is a global trend towards expanding the franchise in national elections to include non-resident citizens and I have argued that this expansion of the demos can be justified for first-generation emigrants who remain stakeholders in democratic citizenship of their countries of origin. I have also argued that the franchise at the local level differs in this regard from that in national elections and depends on residence rather than citizenship in many European and South American democracies. I would welcome if the author corrects the misrepresentation of my work. Rainer Bauböck

Thank you for pointing to a necessary clarification. In your work, you discuss electoral rights in relation to citizenship, noting indeed the world trend of countries granting electoral rights to their citizens living abroad. In the work I cite here, you propose stakeholder citizenship as an alternate way of dealing with the question who should be allowed to vote in a polity. It has been my interpretation of your work that the reasons why you would argue that second+ generation non-resident citizens should not be allowed to vote in the polity of origin are similar to those why non-citizen residents should be, and this is linked to being a stakeholder. I understand that the latter term relates. for you, to a lot more than just residency, and I can understand how the wording of my citation of your work could be interpreted as misrepresentation of your argument. This has now been corrected. In any case, your work has been an inspiration and I thank you for taking interest in mine.