One way globalisation influences politics is by making new social categories ripe for politicisation. Nils Steiner, Matthias Mader and Harald Schoen examine the case of 'winners' and 'losers' of globalisation. They reveal how significant proportions of citizens see themselves as part of these groups – and show distinct party preferences as a result

The democratic world is changing. There are new political parties and movements. The radical right is politicising issues such as immigration and European integration. And the vote choices of social groups are shifting. These developments reflect the emergence of a new cleavage – a new line of conflict that structures political competition.

New group messages are part of this change. In the USA, Donald Trump addressed 'the forgotten men and women of our country' whose wealth 'has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed all across the world'. France’s Marine Le Pen vowed to protect 'the France of the forgotten' against the interests of a 'globalised elite'. German radical-right populist Alexander Gauland portrayed his party, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), as representing the 'ordinary people' in their struggle against a 'globalist class'.

France’s Marine Le Pen vowed to protect 'the France of the forgotten' against the interests of a 'globalised elite'

These are examples of new group-based appeals; that is, claims by political elites to represent a specific group. As a result, voting decisions can be based not only on which party represents voters' policy preferences, but also on which party represents their social identity.

Evidence is accumulating that voting decisions are now influenced by different group identities than they were in the past. According to one study, citizens today identify with their educational class, and vote based on this identity. Another study shows that feeling close to fellow nationals and distant from cosmopolitans increases the likelihood of voting for radical-right parties.

These findings are evidence of the emergence of a new political cleavage with its roots in new identities. This could complement, or possibly even replace, traditional cleavages. The findings also suggest that the identity component of the new cleavage might be multi-faceted and may vary across countries.

'Winners' and 'losers' of globalisation also represent new social categories around which group identities can form. The 'losers' in particular have attracted attention in both scholarly work and public debate. The label applies to people who are negatively affected economically by globalisation or who, because of their cultural views, see the greater social openness that comes with globalisation as a threat to their preferred way of life. Crucially, the losers of globalisation are seen as the voters responsible for the recent electoral successes of right-wing populist parties and politicians.

The 'losers' of globalisation are seen as the voters responsible for the recent electoral successes of right-wing populists

What has been missing, however, is evidence that a meaningful proportion of citizens actually see themselves as losers and winners of globalisation, and that such self-categorisations are related to vote choice. We provide evidence in a recently published study focusing on Germany.

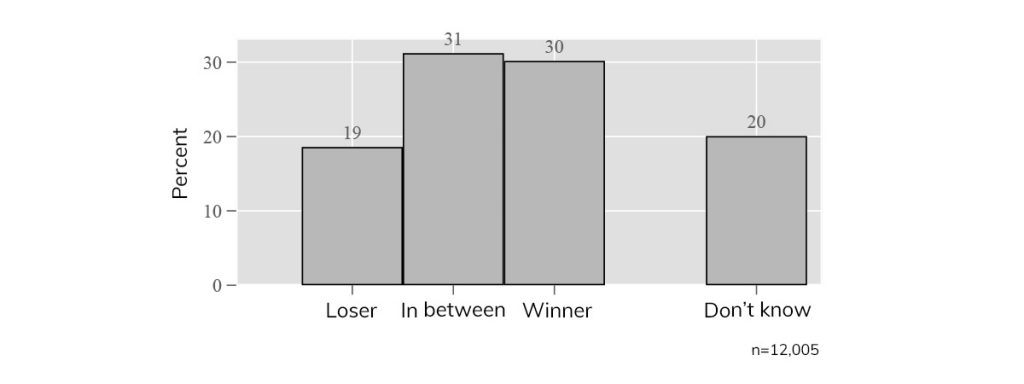

About one in five Germans self-categorises as a loser of globalisation. One in three, meanwhile, self-categorises as a winner. The rest see themselves as in-between or do not know how to respond.

Just because people perceive themselves as being part of a group does not, of course, mean that this affiliation is particularly important to them. In other words, the percentages of citizens with fully formed winner and loser identities are likely lower than indicated here. But even taking this into account, our findings point to the considerable political potential of these categories.

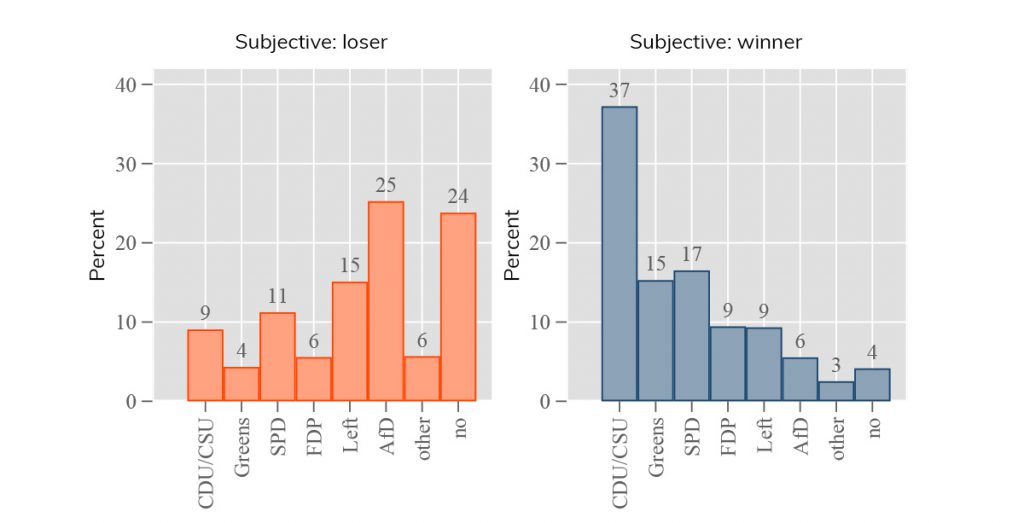

Subjective winners and losers differ in their party preferences. Subjective losers are most likely to indicate a voting preference for the radical-right AfD (25%) or no voting intention at all (24%). Only about 30% indicate a preference for one of the established parties (CDU/CSU, Greens, SPD and FDP).

More than three in four subjective winners, in contrast, prefer one of the mainstream parties. Most often, this means the CDU/CSU, which champions globalisation and Germany’s export-oriented growth model. These differences hold up when we statistically control for additional variables, such as subjective class membership and whether people think they get a fair share.

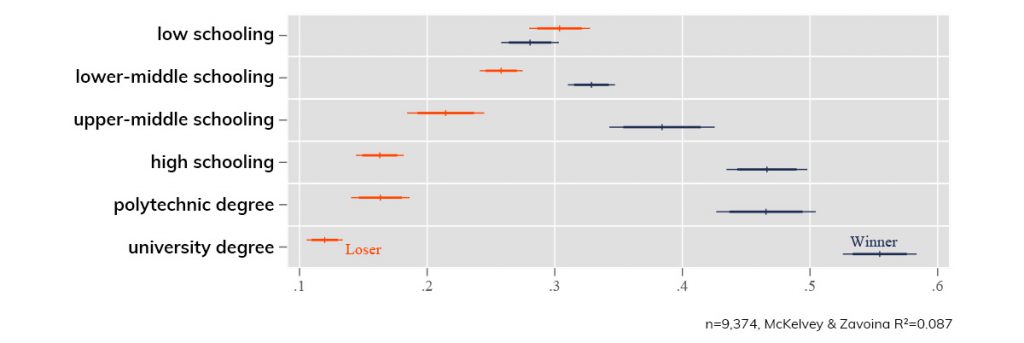

These group-psychological phenomena have their roots in socio-structural characteristics, but the link is not one-to-one. As you can see in the figure below, university graduates are much more likely to perceive themselves as winners (with a probability of 55%) than as losers of globalisation (with a probability of only 12%). In contrast, individuals with the lowest level of formal education are equally likely to self-categorise as losers versus winners.

Thus, there is some connection. But it would be a mistake to dismiss identification with these relatively general categories as mere transmission belts of structurally based interests.

At this point, we return to the group-based appeals with which we began. Politicians do not only offer policy bundles to voters: they are also identity entrepreneurs. They introduce social categories into political discourse to make complex interrelationships comprehensible. In the process, they unite economically and culturally heterogeneous supporters under one banner. The more inclusive these categories are, the larger the group of potential supporters.

Politicians do not only offer policy bundles to voters; they are also identity entrepreneurs

Once politicians have convinced group members that they are 'one of them' – no small feat in itself – they can harness the political potential of the new identities they themselves have (co-)created and convert it into political support.

A classic argument of earlier analyses of political competition is that it is organised around enduring cleavages only when stable identities hold the competing groups together. Our study of the winners and losers of globalisation cannot say much about the categories' stability. Nor can other studies dealing with new identities. On the elite side, political entrepreneurs still seem to be searching for the right language, trying out different categories in different countries.

Will simple dichotomies such as those present in the past – labour versus capital, for instance – emerge? At this point, it remains unclear. What does seem clear is that identity-building rhetoric, starting with the social categories used to appeal to the electorate, will play an important role in determining who can establish themselves as representing the larger group. Thus, such rhetoric determines who can better exploit the political potentials of globalisation.