As Ukraine faces an urgent need to mobilise, focus has shifted to enticing the Ukrainian diaspora to enlist. Using population data from various sources, Eban Raymond explores the multifaceted legality of Ukraine’s repatriation initiative, and questions whether it breaches human rights and international law

Ukraine has been waging a parallel war to Russia’s invasion; one vital to the nation’s continued resistance. With Russia enlisting around 30,000 men every month, Ukraine needs to increase its recruitment sixfold simply to keep pace. Attention has thus turned to Europe’s vast Ukrainian diaspora, which includes those who fled as legal refugees, and those who left to avoid conscription.

Earlier this year, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed various bills designed to empower Ukraine’s mobilisation initiatives, including lowering the enlistment age from 27 to 25, and rolling out an online conscription register.

Of course, it is one thing to ratify laws that streamline recruitment, another to incentivise citizens abroad to enlist. As time runs out and options dwindle, the need to replenish depleted reserves grows desperate. With the co-operation of European states, Ukraine has opted for a carrot-and-stick approach to the conscription of men living abroad. Carrot aside, the legal implications of the stick could constitute a violation of human rights.

Between 23 April and 18 May 2024, Ukraine suspended consular services abroad for men aged 18 – 60. To pressure them into registering with recruitment services, the government prevented this age group from renewing vital documentation, including passports.

Ukraine's government has prevented male fighting-age citizens living abroad from renewing their passports

In Poland, Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski advocated for cutting welfare payments to fighting-age Ukrainians. A senior minister in the German state of Hesse similarly pointed to support from regional German states as a way forward. However, no substantive mechanisms in laws or bilateral treaties exist for repatriation. Regardless, international support for Ukraine’s initiative at governmental level has remained reasonably high.

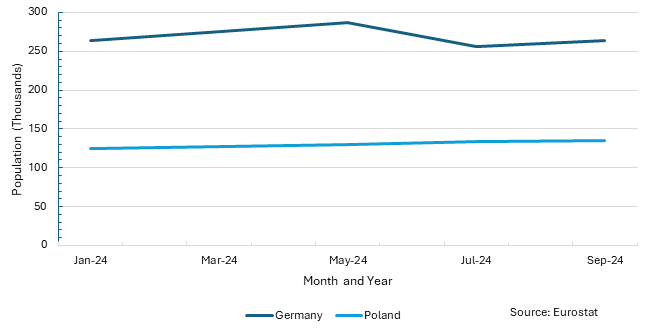

Using data from Statista, I found that Germany and Poland respectively had the first- and second-highest number of Ukrainian fighting-age men in Europe. In both nations, mechanisms by which men can be conscripted into Ukrainian armed forces are the subject of much controversy.

The number of Ukrainian men in Poland has remained relatively stable. In Germany, however, there was a sharp dip after May, when the Ukrainian parliament’s mobilisation bill came into effect. There could be many reasons for this, but we cannot rule out a causal link.

As the conflict enters its third winter, Ukraine hopes to recruit 160,000 more people. Gentle pressure may no longer be sufficient to fulfil Kyiv’s manpower needs.

The imposition of martial law in 2022 prevented all men aged 18–60, with a few exceptions, from leaving Ukraine. Article 65 of Ukraine’s constitution stipulates that ‘defence of the Motherland’ is all citizens' duty, in line with national law. Martial law curtails a number of civil liberties, but exemptions include Article 47, which guarantees accommodation to all citizens.

Even with this Article active, however, access to accommodation may not be feasible. Were consular services suspended again, Ukrainians abroad risk losing out on the EU’s temporary protection programme. This programme guarantees a host of benefits, including housing and welfare, to those who hold a valid passport.

Ukrainian men who lose their legal status outright may thus also lack access to benefits in their host country. At the very least, the loss of housing would mark a violation of basic human rights. A possible decision to restrict welfare payments further, limit access to bank accounts, and implement other punitive measures may force the issue.

To pressure citizens abroad to enlist, Ukraine's government is limiting access to bank accounts and implementing other punitive measures

It is important to note that individual states are responsible for instituting these restrictions. Ukraine cannot influence other countries' policies toward its citizens. As the waters become murkier, it grows harder to pinpoint who is responsible for what. Would Ukraine protest Poland ending educational opportunities for Ukrainian males if it meant thousands of those men consequently enlisted? Beyond hypotheticals, the Ukrainian government has refused to coerce people into returning, so the lines of legality remain unclear.

International law is not legally binding, but it offers a framework by which states can be judged if they are breaching agreed norms. Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that asylum can be granted for victims of persecution, with exemptions for non-political prosecutions. If Ukraine institutes harsher punishments, such as prison time, for draft-dodgers at home and abroad, this could fall under ‘non-political’.

The Council of the European Union provides a clearer definition: 'persecution' can mean punishment for refusing to do things that entail criminal activity. Given the war's chaotic nature, conscripts may sometimes be forced into action they, and the EU Council, consider criminal. From an international perspective, ambiguities like this prevent easy assessment of policies on Ukrainian repatriation.

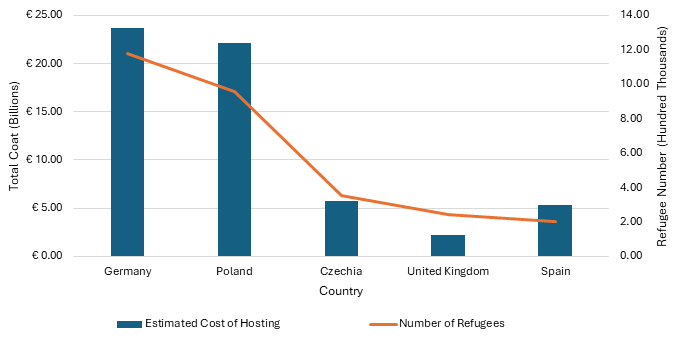

Prior international co-operation with Ukraine shows that military material needs are more important than upholding international agreements to the letter. Given the relatively high cost of hosting refugees, European states may also be more willing to co-operate if they can afford to do so.

The longer the war persists, the more the question of repatriation becomes one of national security. With foreign consent, Ukraine may double down on penalties for draft dodgers, and pressure them to enlist. If they do not, the penalties may percolate further into that legal grey zone of which lawmakers have already warned.

That is not to say Kyiv can apply only punitive measures. Indeed, financial incentives such as tax breaks and welfare benefits could, for reluctant recruits, sweeten the appeal of military service.

So far, Kyiv has imposed punitive measures only on reluctant recruits, but financial incentives, too, could sweeten the appeal of military service

As soldiers tirelessly defend Ukraine, hostility has taken root against those perceived to be avoiding their national duty. Assuming Russia’s continued hostility, Ukraine must weigh up its decision to rely on increasingly coercive repatriation. In so doing, it is kicking a hornet's nest, with potentially dangerous consequences.

Although I view Russia as the aggressor since February of 2022, I have to oppose Zelensky's policy of forcing men, soley due to their sex from seeking sanctuary abroad. This policy of Zelensky is a violation of equal protection REGARDLESS of one's gender. To force even unsuitable men to stay in a war zone and to be eligible for forced military service when able-bodied military-suitable women DO get a chance to leave is unjust. Were it not for Zelensky's misandrist (anti-male) policies, I could then get behind him. As it stands, I cannot and I support those men who chose to disobey these mobilization orders. It is the duty of all other nations who believe in human rights to give men the same treatment they give to women and children!

I served in Ukraine for a year when the war started. The first year, people were enthusiastic to fight from all nationalities. But after a year, everyone realized that it was a proxy war like Vietnam and Afghanistan and so on. As a Ukrainian citizen, I lost my enthusiasm and realized that it was just fighting for a regime represented by a joker who were sending every youth to be killed for nothing. I left the country and so did hundreds of thousands of other youth. For people, they need to wake up, look at their options and get a better understanding of the history. They should know it is always about Russia, America and the jewish state. The rest of the world are sheep! Wake up.