Illiberal populists politicise regulatory agencies. Under populist governments, regulatory agencies engage primarily with interest groups which enjoy close connections to the ruling parties. This is bad news for democratic quality and the quality of governance, write Rafael Labanino and Michael Dobbins

Is there good governance under populist rule amid rapidly eroding democracy? This question is becoming ever more relevant, with sweeping populist victories across the globe in new and established democracies alike. Our new article fills in one piece of the puzzle.

There are significant differences between countries' systems and processes of interest representation. Still, as a rule of thumb, what matters is under what rules and how transparently societal interests are involved at different levels of the policymaking process.

The involvement of societal interests in policymaking and governance matters, as a democratic principle but also in terms of governance quality. The two are in fact intertwined. Societal interests, such as clean energy groups, patients’ associations, and organisations of medical professionals and academics provide not only technical expertise but also political and policy feedback to decision-makers and regulators.

Clean energy groups, patients’ associations, and professional membership organisations all provide technical expertise and policy feedback to decision-makers

The less arbitrary and more transparent interest groups' access is to decision-makers, the less able groups and political parties are to capture policymaking processes to serve their own interests. Greater inclusiveness and transparency ensure a greater variety of interests are heard. This seems like a win-win: a necessary – though not sufficient – condition of good governance.

We would normally assume that interest groups’ access to policymaking in the government and legislature would be more politically influenced than for bureaucracies running the day-to-day business of governance. Moreover, this is the most technical level of governance, where the most direct feedback on policies can be provided (and is required). That is, regulatory agencies – even more than central, ministerial bureaucracies – should, theoretically, be the most open to feedback and expertise from a large variety of interest groups in their respective policy fields.

It is thus a decisive question whether populist rule affects access to regulatory agencies, and how.

All populisms are not the same. Populist movements purport to represent the people against a corrupt and incompetent political elite. Otherwise, they have quite different ideas about how to govern and what to do with the state. Some, such as the Argentinian President Javier Milei, eschew the state and set out to radically dismantle bureaucracies. Others, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, centralise governance at all levels so the state can serve 'true national interests'. And there are those, such as former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, who promise a technocratic government of experts.

But is there variance in how populist governments affect the inclusiveness of societal interests? More than 400 Czech, Hungarian, Polish, and Slovenian national-level energy policy, healthcare and higher education interest groups that filled out our survey helped us to answer these questions. We conducted the survey in 2019 and 2020.

In Slovenia, our fieldwork period preceded the populist and illiberal third Janez Janša-government (in office 2020–2022). Thus, a country in our sample was not under populist rule.

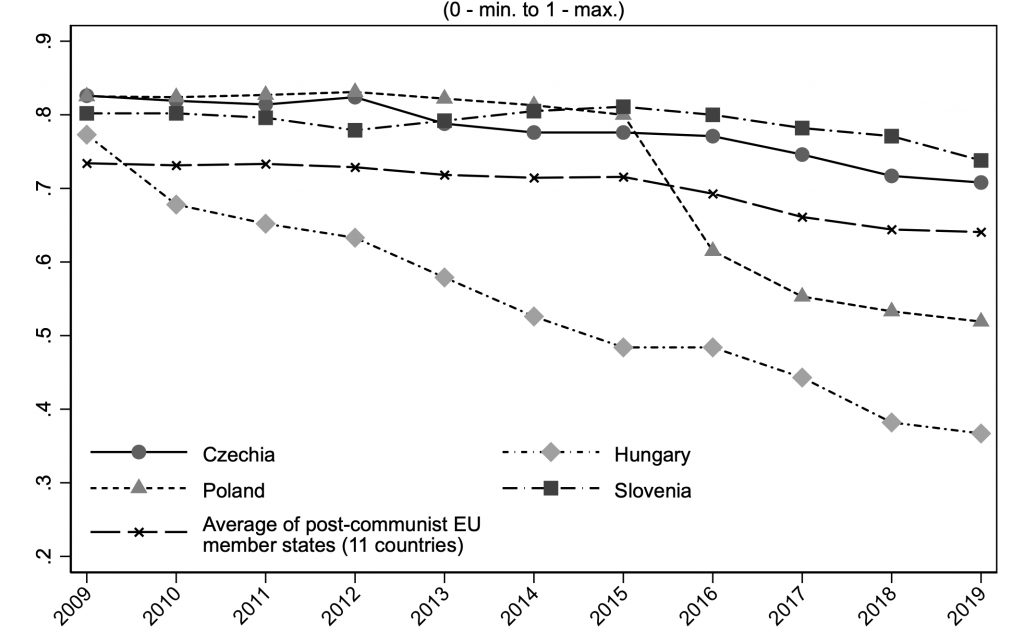

The other three countries were all under populist rule at the time. Nevertheless, the level of illiberal populism and democratic backsliding differed between the three:

Among the three countries, Hungary experienced the steepest decline in democratic quality. Poland was also subject to rapid backsliding. Czechia, in comparison, experienced only marginal backsliding. Hungary and Poland had increasingly extremist nationalist governments. The Czech ANO party under Andrej Babiš was, at the time, still a member of the European liberal party family (ALDE), and followed a technocratic doctrine.

We have some good news. Let’s start with it. We measured the level of interest groups’ access to regulatory agencies against the frequency of their meetings over 12 months. We found that investing in expertise provision and internal development (training of staff, lobbyists, fundraising) affects the frequency of meetings positively.

Our findings suggest that investing in the training of staff, lobbyists, fundraising does indeed get you more meetings

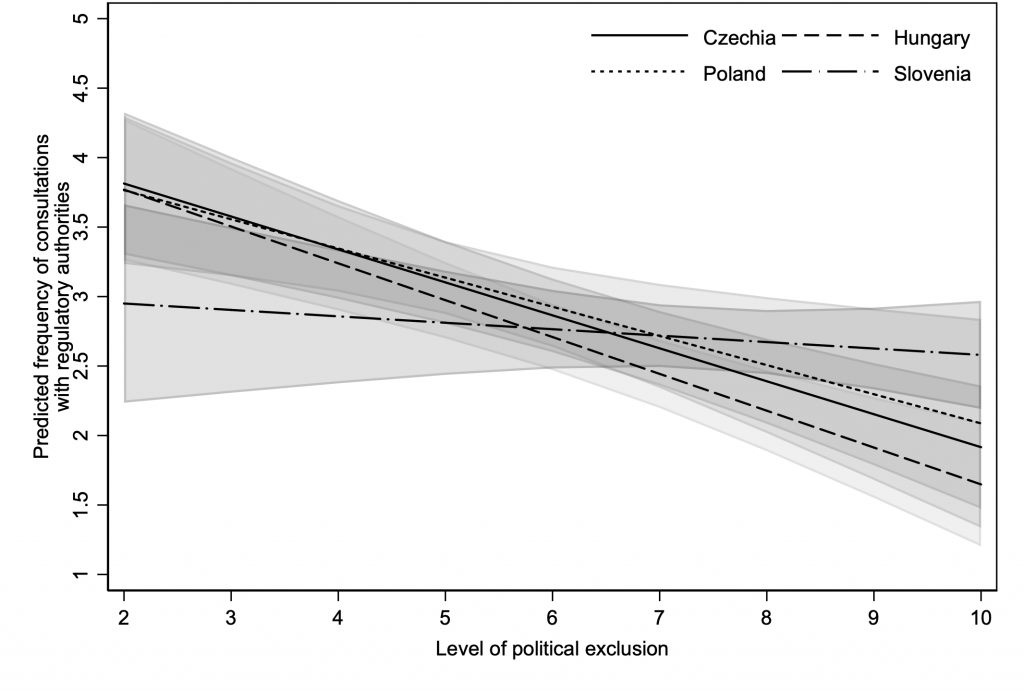

And now the bad news. In the three populist countries, political exclusion – low-level access to governing parties, parliamentary hearings and committees – means less frequent meetings with regulatory agencies for interest groups. Not in Slovenia though, where political access does not seem to play any role in explaining access to regulatory agencies:

The graph above shows how the level of political exclusion explains the frequency of meetings in the four countries based on multivariate statistical analysis. In Slovenia, interest groups meet with regulators about twice a year on average (about 3 on the 5-point scale) regardless of their level of political exclusion. In Czechia, Hungary, and Poland, though, political access also has a strong correlation with access to regulators. Politically well-connected groups can expect, on average, monthly meetings with regulators. Politically excluded groups are lucky to access regulatory agencies once a year.

Well-connected groups can expect monthly meetings with regulators. Politically excluded groups are lucky to access regulatory agencies once a year

Note that this is uniformly true for the three populist and backsliding countries. Czechia fares slightly worse even than Poland. Thus, the self-professed nature of populist rule does not seem to matter at all. What matters is being politically connected with populist governing parties. Only then can interest groups access regulatory agencies effectively.

Our study holds lessons for the wider public and for interest groups, too, in this age of populism and de-democratisation. As citizens, we must be prepared to mobilise under populist governments if we want them to represent our interests. For interest groups, investments in their own organisational and professional capacities are a must.

Our earlier analyses suggest that branching out to the EU and regional levels, along with intense cooperation with other groups, could mitigate the effects of political exclusion. These strategies can help boost the odds of sustaining access to illiberal populist governments and increasingly politicised regulatory agencies.

No.38 in a thread on the 'illiberal wave' 🌊 sweeping world politics