Political distrust and reduced party identification suggest that political parties are in crisis. Elisa Volpi argues that parties are not in terminal decline, but undergoing a process of adaptation

Given that contemporary democracy is unthinkable without political parties, it's unsurprising that party crisis is attracting a lot of attention. But a final verdict on the decline of these actors has yet to be delivered.

Over the past 30 years, parties have faced challenges including increasing popular disenchantment, falling trust in politicians, reduced party identification, diminishing party membership, and growing electoral volatility. These difficulties, however, are all related to parties as representative agencies, that is, to only one of their main functions.

Rather than evidencing their decline, the strengthening of parties' institutional capacity suggests that they are adapting

Parties also have an organisational and institutional role. They are in charge of recruiting political leaders, and organising the parliament and the government. Scholars such as Peter Mair and Stefano Bartolini suggest that while parties’ capacity for political integration might have declined over time, their institutional role might actually have been enhanced.

No other actor has been able to replace parties in their capacity to formulate policy, organise elections and structure parliamentary life. Rather than evidencing their decline, the strengthening of parties' institutional capacity suggests that they are adapting.

Legislative party switching demonstrates whether parties have maintained their disciplinary abilities in the parliamentary arena. It is a good indication of parties’ ability to function as representative agencies.

Party switching occurs when an elected official changes party affiliation during a legislative term. This is puzzling because we expect deputies to remain loyal to the party that made their election possible. According to Gideon Rahat and Ofer Kenig, the scope of legislative defections allows us to assess whether parties have lost their value or if they still hold a fundamental reason for being.

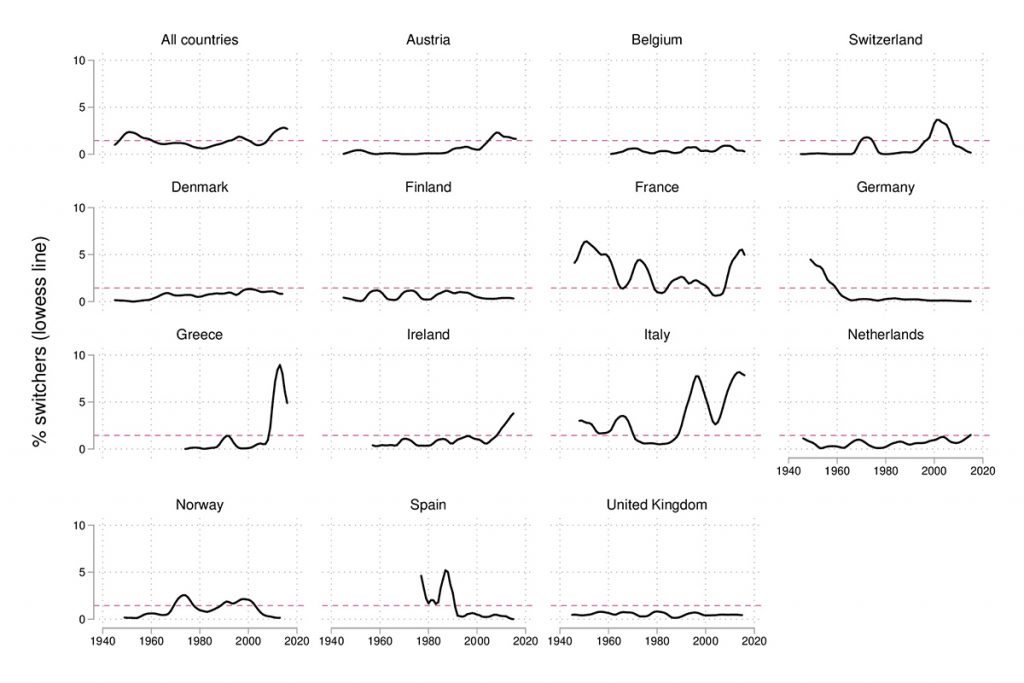

Taking advantage of a unique data set on all the switches that took place in 14 Western European democracies, I show that party switching has increased in recent years but remains generally low.

I analysed the percentage of legislators that changed party during a term. The graphs below show the average number of defectors, by country. Aggregating all countries together, just 1% of parliamentarians change party at least once between two elections. Most countries’ means are below 1%, with two notable exceptions: Italy and France, which both show a mean above 3%.

These graphs might tempt us to conclude that, given the limited scope of switching, parties are still in great shape when it comes to their institutional role. Yet these aggregated averages tell only part of the story. Look at the temporal dimension, and we see great variability across all cases.

Again, France and Italy stand out for their parties' instability, but in the Netherlands, Ireland, Greece, Austria, and Denmark, parties have become more volatile over time. In these countries switching is rare, but in recent years the percentage of switchers has increased substantially.

This development suggests that European parties might experience more switching in the future. But the fact that defections have started to increase only in the last 10 years (with the exception of Italy, an early-comer in this respect) shouldn't lead us to conclude that parties are not faring well. It is too soon to tell whether this phenomenon will continue. Does it represent a new pattern in the relationship between legislators and their parties, or merely a temporary phase of instability?

Is party switching a new pattern in the relationship between legislators and their parties, or a temporary phase of instability?

Political parties in Western Europe have maintained their disciplinary abilities in the parliamentary arena, as evidenced by low levels of switching. The 'partyness' of government and legislatures looks generally strong; legislators tend to be loyal to their groups. The phenomenon of party switching does not, therefore, suggest that the institutional role of parties is in decline.

Parties still look capable of organising and structuring the legislative process, and are still incorporated effectively into the structure of the state, as the cartel party model suggests. According to this model, parties act like a cartel by becoming agents of the state and employing public resources to ensure their collective survival.

As a survival strategy, parties have shifted their emphasis from representative functions to an organisational role

In short, rather than witnessing the decline of political parties over the last 30 years, we have instead seen them adapt. As a survival strategy, parties have shifted their emphasis from representative functions to an organisational role. In this respect, political parties, especially with their relatively high levels of party discipline, remain unchallenged as political actors. They are as important as they ever were to the governance of western democracies.

[…] article was originally published at The Loop (January 26, 2021) and is republished here under a Creative […]