As the political crisis in Peru worsens, Alicia del Aguila explores its roots. Key to understanding it are the political polarisation of recent years, tensions between the Central and Southern Andes, and the historical marginalisation of rural and indigenous people

Following weeks of turmoil, protests against Peru’s President Dina Boluarte have left at least 49 dead and hundreds injured. On Monday 9 January alone, 17 protesters died. At first, protests were contained in the southern regions of Cusco, Puno, Apurimac, Arequipa, and Ayacucho. More recently, however, they have spread to 13 of the country's 24 departamentos. The international airport of Cusco, a popular tourist destination, along with the airport serving Puno, were both forced to close for a few days after violent attempts to seize them.

On 7 December, former President Pedro Castillo mounted a coup d'état. When the coup failed, he was dismissed and imprisoned, triggering a political crisis. To understand how all this happened, we have to go back, first, to the election of Castillo, and then even further, to examine Peru's deeply rooted political tensions.

Between 1990 and 2000 Alberto Fujimori was the (authoritarian) president of Peru. His neoliberal policies minimised state intervention and promoted private investment. This hands-off approach is sanctioned in Fujimori's 1993 Constitution, which still stands today.

Peru returned to democracy in 2001. Since then, its elections have seen a trend for 'anti-system' votes from rural populations, particularly in the Andean south.

Former president Alberto Fujimori's neoliberal policies are sanctioned in his 1993 Constitution, which still stands today

The coronavirus pandemic hit Peru particularly hard. According to Worldometer, the country had the highest Covid-19 mortality rate in the world. Post-pandemic, support for positions critical of the government's management of the economy increased.

In 2021, the presidential election was sharply polarised. Many people simply voted against candidates they considered 'communist' on the one hand, or 'fascist' and 'totalitarian' on the other. Others voted for candidates they considered defenders of the system, and others still for those they considered to be anti-system. Centrist candidates were pulverized.

Far-right candidate Keiko Fujimori, daughter of former president Alberto, and the left-wing candidate Pedro Castillo, represented the two political extremes. With the highest percentages of votes, these two candidates went on to fight a second round.

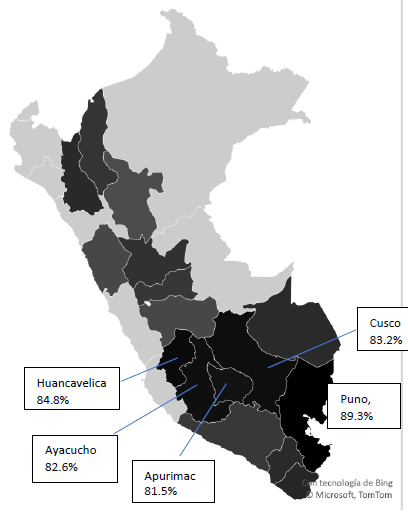

Pedro Castillo, a poor cholo rural teacher, won the second round by attracting the 'identity vote'. In the so-called Andean trapezium (Cusco, Puno, Ayacucho, Apurimac, and Huancavelica), the vast majority of citizens are indigenous. In these regions, Castillo won an overwhelming +80% majority:

Results of the Peruvian presidential election 2021, second round.

Map shows departments where Pedro Castillo won with more than 50% of the vote.

Graphic prepared by the author on the basis of ONPE data

The right-wing candidate Keiko Fujimori won comfortably in Lima, with 65.7%. Her vote was highest in well-off neighbourhoods: 88.1% in San Isidro and 84.5% in Miraflores. However, in a similar scenario to the 2016 Peruvian elections, Fujimori lost the presidency by a small margin, yet failed to acknowledge her defeat.

Afterwards, despite lacking proof of fraud, Fujimori's team coordinated a campaign against the electoral bodies. In a move that attracted indignation, they attempted to invalidate thousands of rural votes.

Thus, even before Castillo took office, the opposition-controlled Peruvian Congress was threatening Castillo with impeachment. From the outset, the press accused him of corruption and bribery, on apparently serious grounds. Castillo's government is also indicted for clientelism and receipt of bribes, which would have depleted Peru's public service in just a few months.

Even before Castillo took office, the opposition-controlled Peruvian Congress was threatening him with impeachment

Castillo's supporters, however, claim those accusations were not the main reason for his 'political prosecution'. Some disbelieve his accusers, or think they are exaggerating their claims. Still others judge that even if Castillo were guilty, his crimes are not relevant. (Peru, they argue, has been governed by corrupt presidents in the past.)

Instituto de Estudios Peruanos data shows that before his dismissal, Castillo maintained important support in the southern Andes, the Amazonia, and rural zones. The strength of that support is based on the historical marginalisation of certain population sectors, particularly rural and indigenous peoples, who identify strongly with him.

The Republic of Peru was founded in 1821. Initially, however, it was only partially liberated from the Spanish, and considered a 'coastal republic'.

In 1824, following victory in Ayacucho, the Republic incorporated the departments of the Andes. Wars among Caudillos, along with intra-regional struggles, dominated the years that followed. The short-lived (1836–39) Peru-Bolivian Confederation was an attempt by the Andean south to decentralise power.

But the Confederation's failure, along with the guano boom, only strengthened the power of the capital, Lima. Peru's catastrophic defeat in the 1879–1883 War of the Pacific made it possible for racist discourse to legitimise the closure of the political system. Elites at that time considered indigenous peoples 'naturally inferior', and blamed them for the defeat.

Electoral reforms in 1895 excluded illiterate citizens from the electoral system. As a result, until as late as 1979, the majority of indigenous and Andean and Amazonian rural dwellers were denied the right to vote. In the twentieth century, however, the great national conflict was related to peasant rights. Yet at that time, most peasants had no voice. They could neither vote, nor be elected representatives.

Peru was one of the last Latin American countries to grant the vote to illiterate citizens, allowing the State to become increasingly detached from rural populations

Peru was one of the last countries in Latin America to grant the vote to illiterate citizens. That ban had allowed the State to become increasingly detached from pockets of rural populations. When the 1979 Constitution lifted this rule, the electoral population in some departments increased by more than 300% in just 15 years. In a phenomenon I describe as 'citizen overflow', Peru's party system was revealed to be extremely precarious. This precarity was borne out by the violence that followed in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In Peru, 45.7% of rural citizens live in poverty. In rural Sierra, more than half of the population is poor (50.4%). Poverty in the departments of Ayacucho, Cajamarca, Puno, and Huancavelica runs above 40%; in Cusco and Apurimac, above 30%.

The catastrophic effects of the pandemic undermined any gains made during the economically prosperous first decade of the twenty-first century. Criticism grew of Peru's clearly fragile economic model.

Congress overthrew Castillo in December 2022. Since then, protesters have called for new elections as soon as possible. Yet given new president Boluarte's disproportionate use of force, demand for her resignation is rising. Protestors are calling for the closure of Congress, immediate elections, and a Constituent Assembly. However, there is no consensus on exactly what constitutional reforms these protestors want.

According to polls, populist demands, including reintroduction of the death penalty, may gain greater acceptance in a Constituent Assembly scenario. Most protesters no longer consider a Castillo presidency to be a realistic prospect.

On the other side, political groups in congress, and others formerly in opposition, are now trying to defend Boluarte's presidency – at least until April 2024. They denounce interference by Bolivia’s leader Evo Morales, who has ethnic ties with the Puno region, as well as the influence of drug trafficking, illegal mining, and other illicit activities. Yet while these factors may play a role in recent mobilisations, they do not fully explain them.

For now, most people expect things to get worse before they get better. Congress endorsed an early election, but only for April 2024. It must now approve the election in a second vote, next February. That's a long time for Peruvian citizens to wait if serious attempts at dialogue do not materialise.

As I write, thousands of people are travelling to the capital from the provinces to demand Boluarte's resignation. A deepening of the crisis, and yet more violence, looks ever more likely.

We Peruvians are 'condemned' to understand each other, but we do not like to accept each other.

I´m not quite sure if Peruvians understand each other. Definitely don't accept each others because the deep racism that showed up (like an x-ray) since Pedro Castillo was a candidate.

But what I´m sure is that Peruvian society suffer of deep complexes and insecurity at all levels. That produces a lack of real leadership.