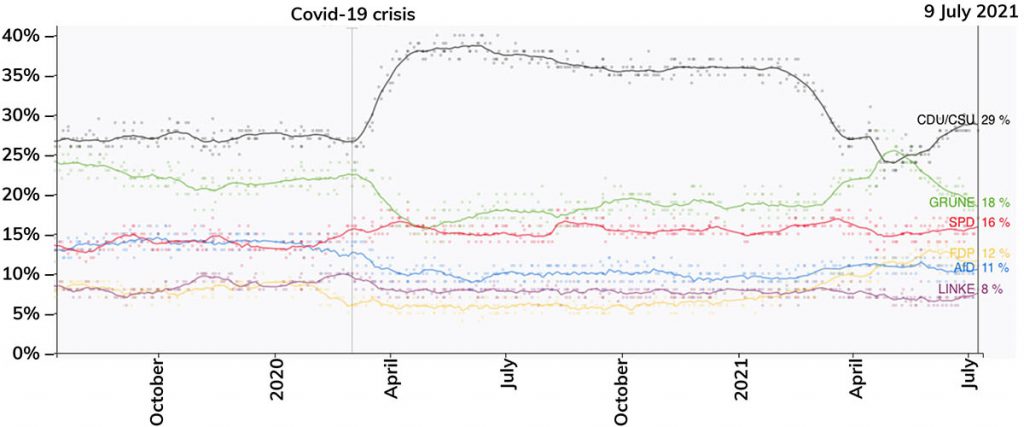

The CDU is facing its first post-Merkel electoral campaign, and the SPD is struggling to gain more than a 15% vote share. The Greens, meanwhile, are the second largest party in Germany. The impact of their results on the new German government may be the Eurozone’s most important political development of 2021. Gabriele Beretta argues that this could also have dramatic macroeconomic consequences for the Euro Area

In the spring opinion polls, the Greens became Germany’s first party. Possible reasons for this could be the difficult CDU leadership transition and internal divisions among the conservatives.

With the consolidation of Armin Laschet at the CDU’s helm, the trend reversed. Small scandals concerning the Greens' young leadership – and especially the candidate, Annalena Baerbock – also played a role. Baerbock enjoyed a mediatic domestic and international ‘honeymoon’ after her nomination as the first party’s candidate for the Chancellorship. This was followed, however, by a more sobering public scrutiny over her capacity and readiness to govern.

For the first time, therefore, the German electorate has had to consider seriously the idea of a Green Chancellor. And even if that's not a realistic prospect, the party maintains nearly 20% in opinion polls and a central position in the German political system. The Greens have governed Baden-Württemberg since 2011 and participate in coalitional governments in 11 of the 16 Länder.

The transformation of a fringe Marxist-environmentalist-pacifist party towards the country's political centre of gravity has been long, gradual and contradictory. Yet nowadays, many of the Greens’ themes and proposals are part of the political and economic Zeitgeist.

However, in addition to their environmentalist core, The Greens have maintained a clear commitment to key social and economic proposals. They want to raise the minimum salary to 12€, introduce a basic income, and hike corporate and wealth taxes. They also intend to use public investment to tackle social and educational inequalities.

in addition to their environmentalist core, The Greens have maintained a clear commitment to key social and economic proposals

The party has been keen to demonstrate its pragmatic, ‘responsible’ and market-friendly credentials while preserving its social and environmentalist identity. Its telling slogan, Radikal ist das neue Realistich (radicalism is the new realism), blends pragmatism and radicalism.

Germany has accumulated huge financial leverage through its past fiscal and trade surpluses. The Greens are pushing for an expansive fiscal policy and, especially, for the continuation beyond 2022 of Olaf Scholz’s fiscal stimulus. They want massive investments to finance a green and social transition towards a transformed, post-Covid economy.

Accordingly, The Greens want to lift or revise the famous German debt brake, which constitutionally limits federal net borrowing to 0.35% of GDP. The procedure requires a highly demanding threshold of two-thirds of the Parliament.

The Greens want massive investments to finance a green and social transition towards a transformed, post-Covid economy

The Greens have campaigned strongly in this direction. They have denounced what they argue is a state of chronic infrastructural, environmental and social under-investment in the country. Despite many political and institutional obstacles, their proposals signal the growing significance of such issues in a large portion of the electorate. These voters are in favour of increasing aggregate demand, and of rebalancing the German economy and its export-led growth model.

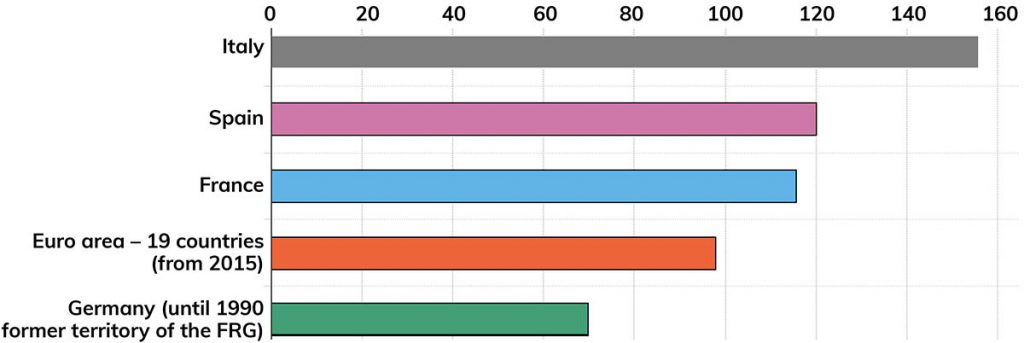

Any eventual rebalancing of the German economy will inevitably spill over into the entire Eurozone. The direction of the next government’s fiscal policy will therefore carry lasting and enormous consequences for other countries that belong to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).

Macroeconomically, an expansive fiscal stance in Germany will benefit other countries’ balance of payments. It will also prevent deflationary and repressive dynamics in the Euro-periphery.

The monetary arm of the EU will be keeping a close watch, too. The European Central Bank has, after all, repeatedly called for greater coordination of fiscal-monetary efforts, and pressured Germany to maintain its fiscal stimulus. The Bank sees complementarity between the actions of fiscal actors and its bond-purchasing monetary policies as crucial to boosting the recovery of the Eurozone, and to reaching its inflation target.

The Greens' programme embodies radical revision of fiscal policy objectives, and a promise of political change

But the greatest consequence of the post-pandemic German budget may be political, setting the tone for Eurozone fiscal policy. The SPD’s leadership, and especially the Finance Ministry, were key players in Germany's historic 2020 turn. At this time, Merkel backed the creation of NextGenerationEU and the provision of grants to crisis-ridden countries. However, under Scholz, the SPD lags behind the Greens, and still lacks a clear political strategy for the post-Covid era.

The SPD is, arguably, still paying the price for a decade-long failure to articulate a coherent counter-narrative to the CDU’s fiscal conservatism, both domestically and at the Eurozone level. The Greens' programme, in contrast, embodies radical revision of fiscal policy objectives and rules, and a promise of political change.

The imminent debate on Eurozone fiscal rules will, arguably, be the central concern of all European policymakers. Stability and Growth Pact rules were halted at the beginning of the pandemic, and the general escape clause will apply until the end of 2022. A return to the status quo ante, with the economic scars of Covid-19 and the average Eurozone public debt set to exceed 100% of GDP, is hardly feasible. Political, institutional, and distributional issues will colour the intense debates and intergovernmental negotiations to come.

The Greens' presence in the new German government – even as junior coalitional partner to the CDU – will have a dramatic impact. The party is proposing substantial changes to the EU fiscal and deficit rules. It also wants to expand NextGenerationEU, and to make it permanent. The Greens have even proposed changing the ECB’s mandate beyond its focus on price stability. They are aiming to include low unemployment and climate-change objectives, and to complete the Banking Union, creating a common guarantee for deposits.

In short, the Greens pose a radical transformational challenge – not just for Germany, but for the entire Eurozone.

The Green Party's surge in Germany will hopefully pave the way to other success stories elsewhere. Europe can no longer wait for a renovated Left, proposing a really alternative albeit realistic development model. All the legacy options at this point can only promise a resounding failure.