Postal voting is praised for its ability to lower the costs of electoral participation. However, Miroslav Nemčok and Johanna Peltoniemi argue that postal voting has its limits. If voters doubt their ballots will make it to the ballot box uncompromised, they are unlikely to exercise their democratic right

Voter turnout has been declining for almost half a century across a wide range of institutionalised democratic regimes. This poses a threat to contemporary democracies: do their election results still accurately represent the will of the people?

One way of responding to this challenge is to decrease the cost of electoral participation. By making voting more convenient, democracies can reverse the decline in voter turnout, and improve representativeness.

Electoral turnout is in long-term decline. So do election results still accurately represent voter choice?

Postal voting is one such option. If voters can cast their ballots via post, those unable to visit a polling station can still participate in elections.

This is why, for example, Australia, Canada, Switzerland, and the US have long offered mail-in voting. Other countries, including Finland, Italy, and Mexico, have recently introduced or expanded their mail-in voting systems.

However, voting by mail presents a dilemma. On one hand, postal voting is an inexpensive and efficient option for those with mobility issues, and for people who live some distance from their nearest polling station. Moreover, as the pandemic obliged voters around the world to cast their ballots remotely, postal voting became one of the most commonly used special voting arrangements. Regardless of why one might choose to vote by post, it offers a workable way for a citizen to participate in their nation’s democratic decisions.

It's a long way from post office to ballot box. Voters must therefore have enough faith that their envelopes will make the journey without interference

Yet, on the other hand, ballots dispatched via postal services can be compromised. This risks jeopardising vote integrity and ballot secrecy. A ballot must pass a long way, almost completely unsupervised, from dispatch at a local postal office to delivery at the ballot box. Voters must therefore have absolute trust that their envelopes will complete the journey successfully.

Considering these two perspectives, postal voting may increase the likelihood of an individual casting a vote. But this only applies if the person has sufficient confidence in the credibility of the entire procedure.

Our study examines the effects of both factors – convenience and trust – in an integrated research design. In 2019, Finnish citizens residing abroad were offered a postal vote in Finland's Parliamentary elections. We teamed up with the Finnish Ministry of Justice to field an extensive survey exploring the motivations of the voters residing abroad. (Voters resident in Finland, unlike their non-resident counterparts, were not eligible for a postal vote.)

In fact, surveying citizens residing outside the country in which they were registered to vote was particularly appropriate to our research goal. Postal voting was an alternative option to in-person voting at polling stations organised by a diplomatic mission outside of Finland. However, for some voters, the nearest such station was in a distant city – or even in a neighbouring country. This allowed us to examine the increasing convenience of voting along a wide range of distances to the nearest polling station, up to distances of 1,000 kilometres.

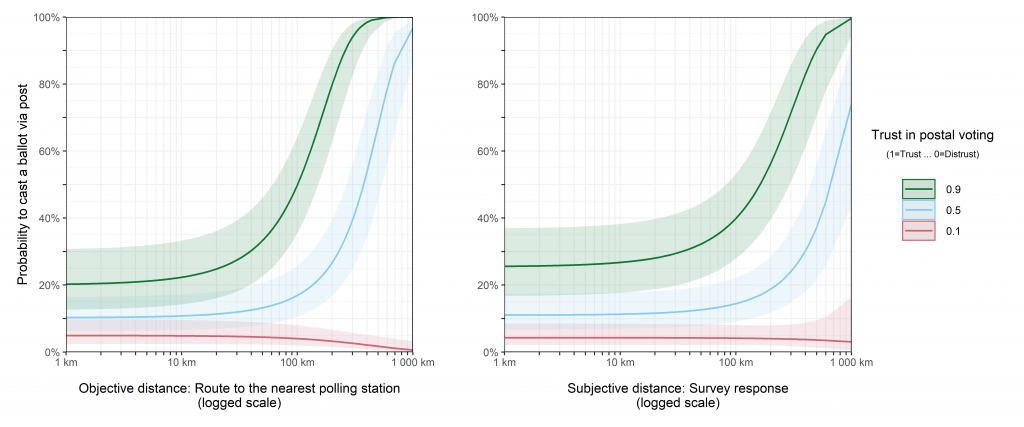

However, surveying voters residing abroad imposes a challenge: Do these voters have accurate information about the nearest polling station? We calculated the distance in two ways. 'Objective' distance used the physical address to which we sent the invitation to join our survey (left side of the figure). 'Subjective' distance asked the respondents directly about the distance to the nearest polling station as an open-ended question (right side of the figure). Both measures not only strongly correlate, they also proved consistent. This gave us confidence in our research findings.

First, examining the two factors separately, both higher trust and greater distance increase the probability that a voter would choose to vote by post.

Assessing both factors at the same time, distance to the nearest polling station has a negligible effect on the adoption of postal voting among individuals who doubt the integrity of this voting method. Regardless of the distance, the probability that low-trusting voters residing abroad will mail their ballot is consistently small (around 5% or less). See the red line in the graphs below.

In contrast, non-resident voters with high levels of trust are four times more likely (around 20–25%) to mail electoral ballots. This is the case even when the nearest polling station is within 10–30km. Beyond this, the probability of high-trusting individuals sending ballots via mail increases sharply. See the green line in the figure.

Higher trust in the postal-voting system, and living a long distance from the nearest polling station, both increase the likelihood of a person choosing to vote by post

Medium-trusting voters stand between these two groups. The likelihood that they will mail in ballots begins to accelerate quickly. Yet, the nearest polling station has to be more than 100km away; see the light blue line in the figure. Until that point, the probability is around 10%.

The Covid-19 pandemic prompted election authorities in many democratic systems to offer a remote alternative to conventional in-person polling stations. Encouragingly, our findings suggest that postal voting does indeed constitute a reasonable solution. However, authorities must address voters' concerns about the integrity of their votes, or postal ballots will never become a credible replacement for the polling station.

To reverse the worrying decline in voter turnout, governments must demonstrate to their electorates that there is little reason to doubt the integrity of alternative voting methods – including postal ballots.