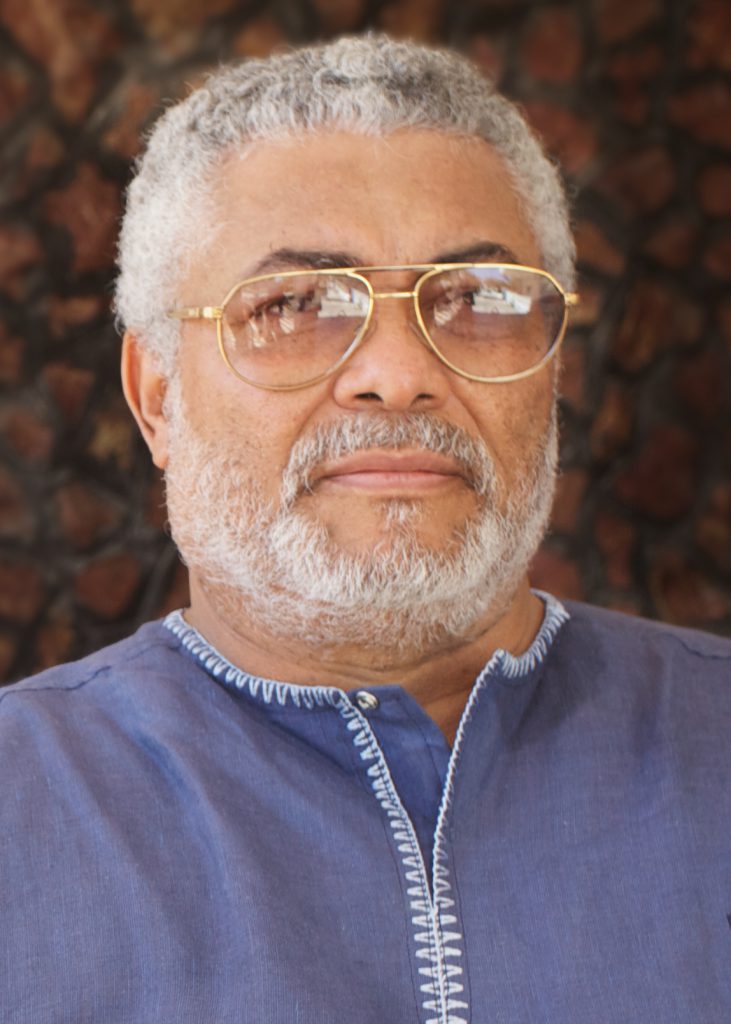

Jeffrey Haynes argues that one of Africa’s most controversial leaders, the late Jerry John Rawlings of Ghana, began his political career as a fiery revolutionary and ended it as a popularly elected president via a liberal democratic political system. But what explains this volte face? Was it ideological conversion or expediency?

In 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from Britain. The country had endured two decades of political and economic volatility and disappointment before Flight-Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings took power. Unelected military regimes followed short-lived, civilian elected governments. The economy tanked. Ghanaians pilloried elected politicians for their corruption.

Rawlings briefly took over in Ghana in mid-1979, returning to power via a military coup d’état in December 1981. He stayed in power for the next two decades: initially as unelected head of a joint civilian-military regime and latterly as popularly elected president. Rawlings claimed he wanted radically to reorganise Ghana’s political system via popular revolution.

When Rawlings grabbed power he was determined to change things. Yet, he did not appear to be sure just how he would change things or what form a new political order would take. Experimenting with local, self-organised, grassroots councils, he found that the system was difficult or impossible to restructure in the way he wanted. Despite attempts to bring the mass of ordinary Ghanaians into the country’s decision-making process, his regime remained heavily dependent on military support.

It turned out that most Ghanaians preferred the devil they knew – flawed liberal democracy – than a socio-political revolution. Rawlings saw the writing on the wall. He moved ideologically from being a fiery revolutionary – arguing for what he referred to as ‘true’ democracy – to a supporter of the same multi-party, liberal democratic system that he overthrew in 1981. He became adept at winning elections.

Rawlings was Ghana’s popularly elected president for eight years (1993–2001). He stood down after two terms as the 1992 constitution demanded. Yet, Rawlings continued to believe that liberal democracy was inappropriate for Ghana, given its level of political and economic development.

Why did Rawlings’ revolutionary populism not develop as he envisaged: a popular democracy, with a pyramidal structure emanating from the grassroots and culminating in a national people’s parliament? Why did the country return to multi-party democracy, the political system he overthrew on 31 December 1981?

In my book, Revolution and Democracy in Ghana, I argue that Rawlings lacked the ideological and institutional capacity to develop a viable popular democracy. In addition, his preferred political system was not clarified to the extent that most Ghanaians clearly understood what he intended. His fuzzy desire to craft a new political system was no match for the wish of opposition forces – internal and external – to return to multi-party democracy. It was a political system, it turned out, which most Ghanaians also preferred.

Following the end of Rawlings’ presidency in 2001, multi-party democracy endured in Ghana. According to the US National Intelligence Council:

Following two decades of rule under Jerry Rawlings, Ghana … emerged as one of Africa’s most liberal and vibrant democracies, reclaiming a position of political leadership on the continent

Us national intelligence council, 2008

In 2022, Freedom House designated Ghana as ‘free’. It is one of only a handful of Africa’s 54 countries to hold this designation.

Rawlings died in November 2020, reportedly of Covid-19. His political legacy divides Ghanaians. Some regard him as a reprehensible military dictator, who presided over a lengthy period of significant political oppression and curtailment of freedoms, involving disappearances and incarceration of opposition figures, substantial media repression and a societal ‘culture of silence’.

However, many Ghanaians regard Rawlings as a national hero. He is widely known as ‘Junior Jesus’ and ‘Papa Jerry’, second only to Ghana’s first post-independence president, Kwame Nkrumah, in national estimation. In particular, Ghanaians thank Rawlings for saving their country from economic ruin in the 1980s; preventing Ghana becoming a failed state, while facilitating democratisation.

Rawlings failed to develop his vision of popular or ‘true’ democracy. But the political organs his joint civilian-military regime established – grassroots defence committees – were important for Ghana’s democratic development. Defence committees and their successors, Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs), were a crucial bridge between Rawlings’ unelected civilian-military regime in the 1980s and the liberal democracy which followed.

Defence committees and CDRs were important institutional bases of Rawlings’ political party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC). Partly in response, the anti-Rawlings opposition coalesced to form a rival party, the New Patriotic Party (NPP). The NPP gained power in January 2001, when Rawlings stood down as president. Over the next two decades, the NPP and NDC alternated in power.

Today, the NPP government of President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo is in power. The next presidential and parliamentary elections are due in late 2024. Most observers expect the NDC to win them.

In 2022, Ghana experienced significant anti-government demonstrations in its capital, Accra. The protests were organised by a new movement, #AriseGhana. Its activists were ‘protesting against worsening economic conditions – inflation is running at 37% and a third of people under 30 are unemployed’ – as well as against new taxes.

Many Ghanaians would agree that Rawlings’ values and legacy – social justice, equality, and probity – are now comprehensively absent in Ghana

Many Ghanaians would agree that Rawlings’ values and legacy – social justice, equality, and probity – are now comprehensively absent in Ghana. Circumstances similar to those which led to AriseGhana were present when Rawlings and his comrades mutinied in May 1979.

That said, the world is very different today. The Cold War is long over; there are no clear ideological divisions between Ghana's leading political parties. Ghanaians are weary of political conflict and economic disappointments. Dreams of a self-sufficient economy are untenable in the realisation that economic globalisation cannot be avoided, least of all by economic autarchy or popular power à la Rawlings.