Niva Golan-Nadir examines the origins of alternative politics in the form of co-production of essential services. As an example, she looks at the provision of public transport services in Israel on the Shabbat. She models the way this comes about, how it works, and considers its implications for democracy

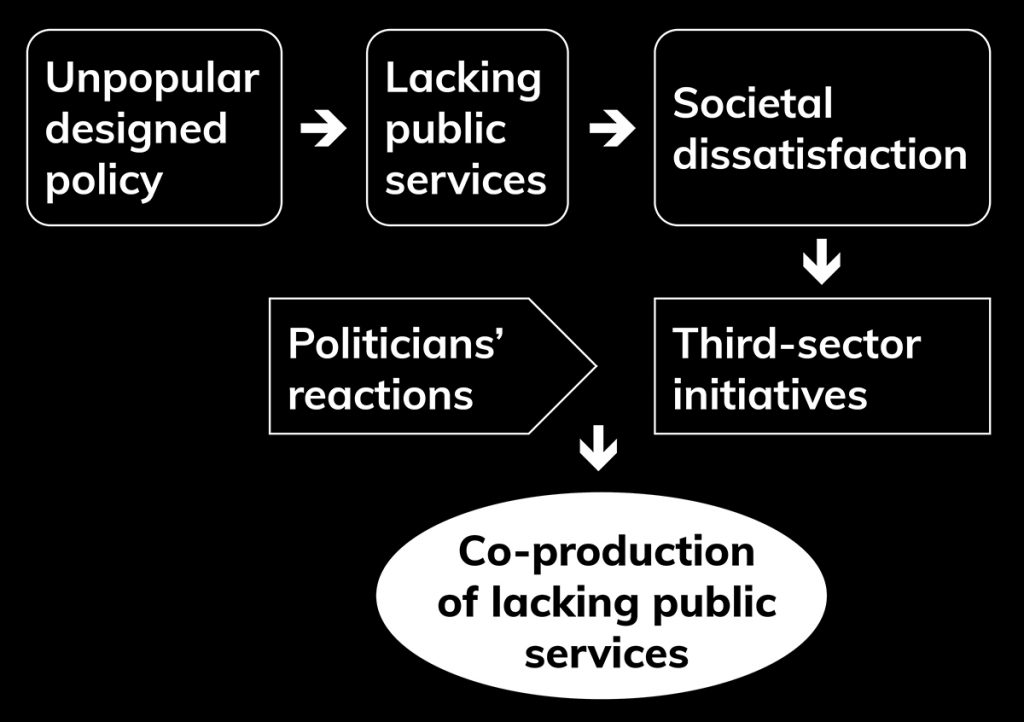

At times, citizens become dissatisfied with public policies, particularly when a policy leads to the lack of a service they want and need. Citizens find different ways to overcome their dissatisfaction. If they have the desire and resources, they may ultimately try to produce those essential services themselves. In doing so, citizens initiate a process that leads to the ‘co-production’ of the absent service.

Co-production is a bottom-up process that relies on collective action

Co-production, then, refers to the collaboration between service users and providers. Its aim is to either raise service quality, or even to ensure that the service is indeed provided. We can see co-production as a bottom-up process that relies on collective action. Dissatisfied citizens may encourage the formation of third-sector organisations to rise to the need. Then, as politicians and street-level managers become engaged, the co-production of public goods and services takes place.

The source of citizens' dissatisfaction (condition 1) is administrative burdens (i.e. missing public services) caused by the policy as designed. The co-production process is initiated by ideology-driven third-sector organisations operating as high-tech enterprises (condition 2) urging local politicians to use their expertise as service suppliers for their political gains (condition 3).

The means by which the provision of public transport on the Jewish Shabbat (Saturday) in Israel has come about is an excellent example of the ‘co-production’ process.

Israel defines itself constitutionally as a ‘Jewish and democratic state’. This unique official character, however, creates a basic difficulty in separating state and religion. Among Jewish Israelis there is broad consensus that Israel should be a ‘Jewish state’. However, deep controversies exist over the meaning of this. Several policy principles are fundamental to Orthodox Judaism. Among them is the Jewish Saturday, Shabbat, which includes a ban on public transport.

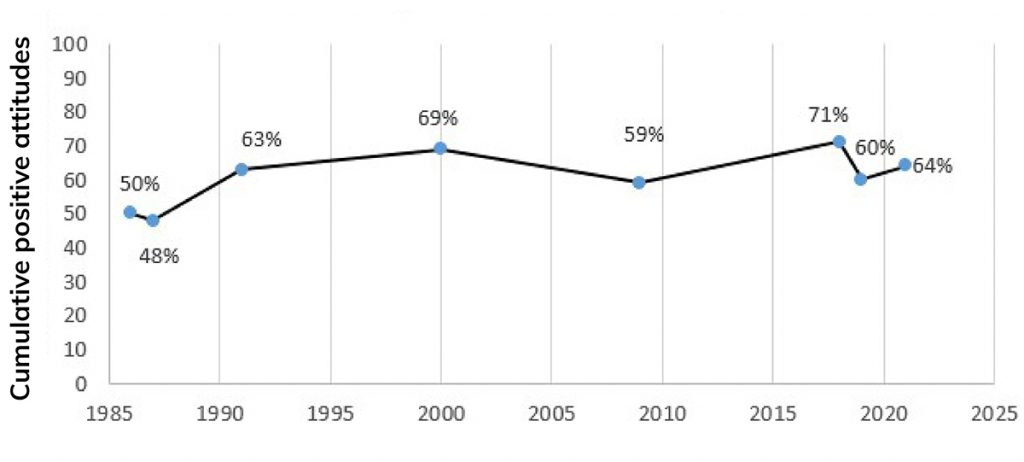

Public opinion surveys show that the majority of Jewish Israelis want the religion-based public transport policy to change:

In early 2022, I conducted a survey at the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University. Among Jewish Israeli respondents, 43.4% said they completely agreed and 19.6% mostly agreed that Israel needs to provide public transport on Saturdays, except for in highly religious areas. This contrasts with the 35.5% who mostly disagreed or disagreed completely.

Despite the views of a significant minority of ultra-Orthodox citizens, more than half of Jewish Israelis do seem to want public transport on the Shabbat

Divided into levels of religiosity, 88.6% of secular respondents 'mostly or completely agreed', as did 61.9% of traditional, and 20% of religious respondents. Predictably, however, among ultra-Orthodox respondents, none agreed. Yet overall, 54% of respondents 'mostly or completely agreed' that the state should be in charge of initiating Shabbat public transport services.

The co-production initiative in relation to transport services emerged from below. The process was triggered by a shortage of resource among third-sector organisations. Local politicians and street-level managers reacted to that shortage, and began to seek political gains.

Since 2015, two substantial civic initiatives have established public transport services in more than 15 cities across Israel, including Shabus in Jerusalem, and Noa Tanoa in Tel Aviv. Motivations for doing so include helping disadvantaged populations, and people of low socioeconomic status. These groups include young people, senior citizens, tourists (especially those travelling between Tel-Aviv and Jaffa), and people with physical disabilities. Having succeeded in providing these services locally, civic associations reached out to city councils to expand availability of public transport on the Shabbat.

When the service gained popularity, municipalities joined the civil effort. Our interviewees acknowledged that pressure from local citizens made municipalities more interested in offering the service. Before the 2019 local elections, candidates canvassed public opinion to draw up their manifestos. In so doing, they discovered significant demand for public transport on the Shabbat.

Municipalities then turned to third-sector associations that know how to operate effectively. They wanted short, efficient inner-city lines, proper timetables, and effective publicity. To overcome Shabbat restrictions, the local service runs free of charge for users, and is funded using municipal budgets.

Citizens dissatisfied with transport policy formed organisations to provide transport services. When the service became popular, politicians got involved

To date, the national government has not involved itself in the service, yet nor did it choose to ban its existence.

In sum, citizens' dissatisfaction with existing transport policy resulted in the formation of third-sector organisations to provide transport services. When the service became popular, politicians and street-level managers got involved, leading to the co-production of public transport in Israel.

Co-production might provide remedies for societal dissatisfaction in societies that suffer from cleavages (social, ethnic, religious) which limit the options for policy-making in various fields.

From a democratic perspective, we might see this phenomenon as beneficial to the participation and inclusion of people and their collective initiatives, especially if it promotes the interests of disadvantaged groups.

At the same time, if conducted solely at local level, we could also consider co-production a threat to the stability of a democratic system. Indeed, the provision of large-scale services at local level may increase inequality between wealthy and poor local authorities. It may prevent the allocation of local budgets from other mandatory essential local services such as healthcare, education, and culture, and increase the power of local politicians who co-produce the service to attract electoral popularity. But however we look at it, the phenomenon looks set to stay – at least in Israel.