Political scientists assume that foreign rulers respond to domestic resistance in one of two ways: by repressing their subjects, or conceding to their demands. Yet, write Joan Ricart-Huguet and Richard McAlexander, there is a third option. Weak states may use a strategy of state disengagement

Political scientists have long studied resistance to foreign rule, from anti-colonial movements in Africa to recent events in Afghanistan. Short of complete withdrawal, it is often assumed that the occupying government or colonial state has only two options. They can either repress their subjects, or concede to (some of) their demands.

In a recent article published at International Studies Quarterly, we argue that there is a third option – state disengagement – whenever subjects do not pose a large-scale violent threat but nevertheless engage in active resistance. State disengagement can happen when the state is weak.

State disengagement is the partial withdrawal of the state from some if its territory. It occurs when deploying repressive forces or conceding to demands is too costly or otherwise impractical because of state weakness

The standard repression vs. concession logic assumes that the state is strong enough to punish dissent or to deliver concessions. We define state disengagement as the partial withdrawal of the state from some of its territory (by reducing the levels of public investments in hard-to-rule regions, for example). It implies a reduction of state presence, or of the state’s footprint, typically in peripheral regions. This occurs when state weakness makes deploying repressive forces, or conceding in response to resistance, too costly or otherwise impractical.

We test our argument using historical data from the eight former colonies that composed the federation of French West Africa. The Federation existed between 1905 and 1960. Its member countries were Benin (formerly Dahomey), Burkina Faso (Upper Volta), Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali (French Sudan), Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal.

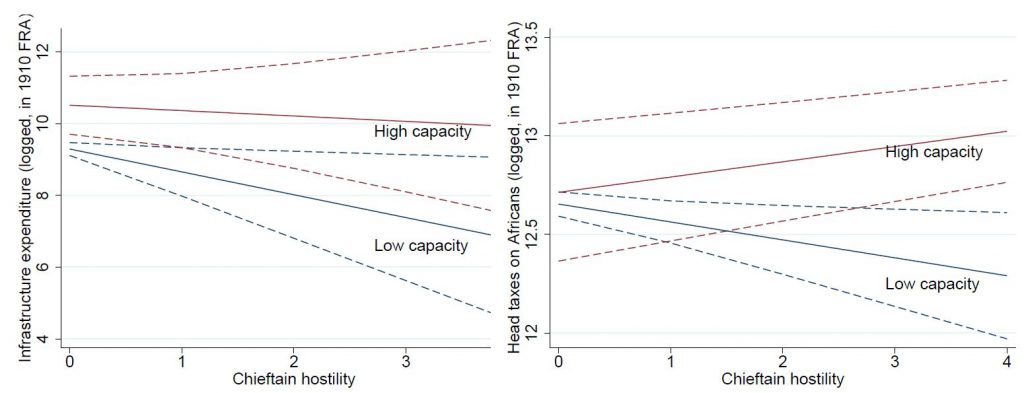

We show that colonial governments reduced public investments in districts where African chiefs engaged in (largely nonviolent) resistance, such as civil disobedience. More surprisingly, we find that 'chieftain hostility' reduced government taxes and fees on Africans, rather than increasing them as punishment. The state was too weak to punish with higher taxation or to concede by increasing investments. West Africans did not pose a threat to French colonial rule until the 1950s. French colonial states could therefore afford to disengage in peripheral, inland districts ('low-state capacity districts').

French West African colonial states could further afford to disengage because colonial borders in Africa remained largely uncontested after the 1920s. All European powers had a thin presence on the ground to reduce costs. The violation of the 'principle of effective occupation' established at the 1884–5 Berlin Conference was something that all European powers benefited from (an equilibrium).

By contrast, in coastal and capital districts (core, 'high-state capacity districts'), the French responded to resistance by African chiefs in a more repressive manner. They reduced public investments but increased extraction via taxation because they did not want their core political and economic interests threatened.

The figure below visualises our findings. We observe that chieftain resistance (described as 'hostility' by colonial authorities) decreases investments in both core and peripheral districts. Indeed, the two slopes of the left graph are nearly parallel. However, our analysis reveals that the effect of resistance on head taxes and fees is negative and significant in peripheral districts, while it is positive in core districts. The two slopes for the right graph cease to overlap in the presence of significant chieftain resistance.

For example, the Tuareg had long controlled parts of today’s Mali and Niger. Hence, they were very hostile to French forces during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The French army used ample violence in the initial military conquest. The French also aimed to reduce their footprint in hard-to-rule areas by encouraging local autonomy for Tuareg-dominated groups such as the Bella.

Low-level and nonviolent resistance can also affect state–society relations and state formation

One consequence of Tuareg resistance was a shrinking of the colonial budget and investments. In districts hostile to French rule, these 'did not dedicate significant funds to social projects, infrastructure or non-military construction'.

In sum, resistance to French rule in the first half of the twentieth century helps explain why development was so unequal during colonial rule. This might also explain why it has remained so unequal in Francophone West Africa ever since. Low-level and nonviolent resistance are often overlooked in the conflict literature. Visible and large-scale violent conflicts, such as Afghanistan, attract far more media coverage. However, low-level and nonviolent resistance can also affect state–society relations and state formation, and may have important long-term effects.

The concept of state disengagement should be useful to social scientists studying various parts of Africa and beyond. The agreement among African governments to respect the borders they inherited at independence may help explain not just the rarity of separatist movements but also why states like Mali practice limited engagement with remote areas today (they can afford to do so because their country borders are not at risk).

Our theory may be of little relevance for Western Europe or most of East Asia, where the state is highly capable and developed. At the same time, we believe it is relevant in relatively weak states beyond Africa. This includes states that have not fully consolidated, such as Myanmar and the Philippines. Recent efforts by people of the highlands of Southeast Asia to maintain their autonomy are one reason why the state’s footprint in those areas has shrunk at times.

Our theory is relevant in relatively weak states beyond Africa. This includes states that have not fully consolidated, such as Myanmar and the Philippines

The menu of available options may be different for weak states when peripheral regions resist. Borderlands are often viewed as ungoverned, chaotic spaces that differ from a country's well-governed core. Our work suggests that these ungoverned spaces are sometimes a policy choice, not a policy failure. Weak states might prefer to consolidate control over their capital rather than extend costly control throughout the entire country.