Niels Nyholt argues that voters’ everyday experiences with political decisions can substantiate populist parties' anti-elitist arguments. When mainstream politicians accommodate changes in settlement patterns by merging schools and hospitals, some communities are left without nearby services. Here, right-wing populist parties offer an electoral outlet for residents feeling left behind

Voters' everyday experiences of political decisions with adverse local effects make right-wing populist claims about a disconnect between the mainstream parties and the people more compelling. A central tenet of right-wing populist parties’ appeal is their anti-elitism. By portraying mainstream parties as a homogeneous political class that only look out for themselves, right-wing populist parties position themselves as the genuine champions of the people. In true fairytale fashion, the populists arrive and fight back on their behalf.

When politicians in power close a school or hospital, the locals take it personally. Residents see such closures, often made in contempt of local concerns, as devaluing their neighbourhood. It therefore strikes a chord with affected residents when right-wing populists describe politicians as arrogant and out of touch. Closures demonstrate clearly that the elite does not care about the local community. In such situations, right-wing populist parties can appear an attractive outlet for frustrated voters.

It strikes a chord with closure-affected residents when right-wing populists describe politicians as arrogant and out of touch

But why would politicians downgrade local communities to begin with? They know that closures risk attracting the ire of their electorates, and politicians depend, after all, on continued electoral success. Nevertheless, the closure of public institutions in thinly populated areas is a common phenomenon across western democracies. In Denmark alone (the empirical basis of my research), 315 schools and 30 hospitals closed between 2005 and 2019.

Politicians may find amalgamating institutions at fewer locations an appealing option because it enables them to claim that they are improving service delivery and cutting costs simultaneously. Service delivery may improve because public employees can further specialise in subfields when they are part of larger entities. Politicians can also argue that expected economies of scale will cut costs. Amalgamating public institutions at fewer locations may thus appeal to politicians from both the left and right.

Amalgamating institutions appeals to politicians because it enables them to claim that they are improving service delivery and cutting costs simultaneously

Furthermore, as people settle increasingly near major cities, politicians need funding for new institutions to accommodate the new residents. They thus end up closing institutions in rural areas where the population base has moved away, and where the absolute size of the disgruntled electorate is minimal.

I wanted to test whether right-wing populist parties do indeed profit from local school closures. Using data from polling stations in Danish local elections, I measured the change in support for these parties in areas that experienced local school closures against the trend in areas that did not. By comparing the changes, I isolate the difference in support that cannot be attributed to common changes across areas, nor to the time-invariant difference in support for right-wing populist parties between areas affected by closures and those areas not affected by closures.

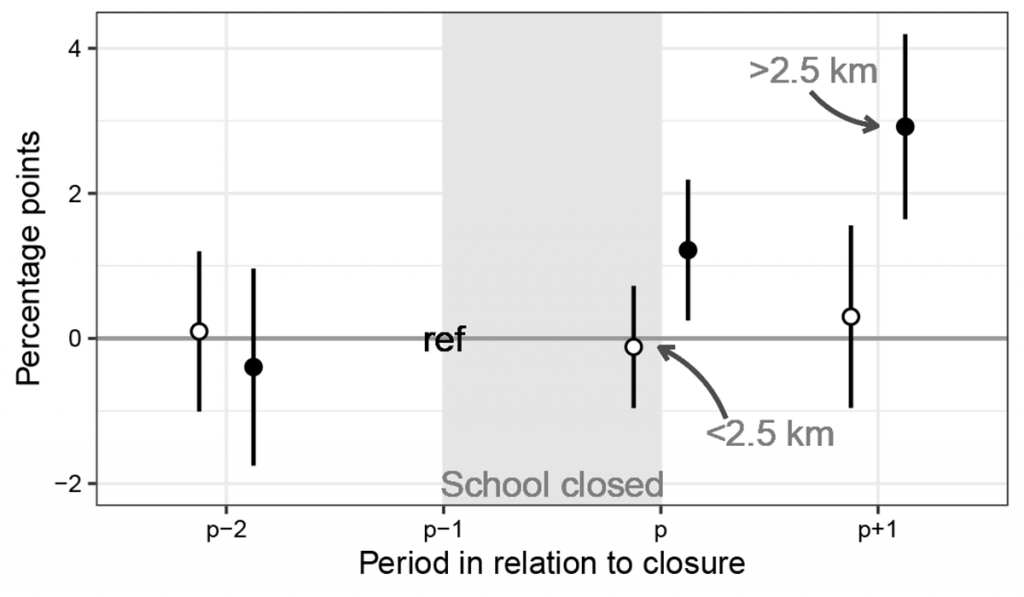

In the figure below, I plot the estimated difference in changes in support for right-wing populist parties before the closure (p-2), in the first election after the closure (p), and in the second election after the closure (p+2). I assume that individuals will respond less severely if there is another school within 2.5 km. I therefore split the affected precincts into two groups.

The black dots show that support for right-wing populist parties increases significantly in the more severely affected precincts. In the election held after the schools' closure, support for right-wing populist parties jumps by about one percentage point in the severely impacted precincts compared with precincts in which no schools closed. This increases to about a three percentage point advantage in the second election after the closure. Given that right-wing populist parties managed to win about 10% of the votes in these local elections throughout the entire study period, this is a significant effect.

In the first election after a school's closure, support for right-wing populist groups jumps by about one percentage point in the most impacted areas

The white dots show that there is little to no difference in the change in support for right-wing populist parties between the lightly affected and unaffected precincts. Thus, people do seem to take the severity of the policy into account.

All groups appear to follow similar trends in support for right-wing populist parties before the school closures. This should strengthen our confidence that voters react specifically because of the school closures, and not because of other differences between the studied precincts.

Previous studies explaining the demand for right-wing populist parties have emphasised both economic and cultural grievances. However, part of right-wing populist parties’ appeal is their critique of the way mainstream parties wield power. As Katherine J. Cramer documents, residents of peripheral regions often feel excluded from decision-making bodies. When political decisions manifested in people’s local area through the closure of public institutions such as schools, my research shows that residents may find right-wing populist parties increasingly appealing.

To accommodate the grievances of rural and deindustrialising communities, governments across western countries have implemented plans to reverse local decline and shift public resources back to these communities. However, it is worth remembering that political decisions such as school closures are motivated in part by depopulation and efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of public service delivery. Dealing with the development of rural and declining regions thus inevitably involves real trade-offs between the interests of those who have left, and those who are left behind.

No.83 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more