From F-35 jets to Tesla batteries, Washington’s reliance on rare earth elements runs deep. China, which refines more than 99% of the world’s heavy rare earths, and supplies 70% of US imports, has repeatedly played this ace in times of tension. Yet, writes Mariam Mumladze, deep interdependence and limited alternatives complicate the standoff

Following the famous statement made by China’s former leader Deng Xiaoping, China quickly realised the geopolitical value of its rare earth elements (REEs). Seventeen metals, in light and heavy forms, combined with other ores produce metal alloys and permanent magnets crucial for defence systems as well as civilian technologies. Today, China refines 85% of the world’s light REEs and more than 99% of heavy REEs, and shows no intention of giving up its dominance:

Lockheed Martin, Tesla, and Apple are among the largest US companies to use Chinese REEs in their supply chains, in lasers, radar, sonar, night vision systems, missile guidance, jet engines, and alloys for armoured vehicles – all critical to US national security. F-35 Lightning II aircraft, Virginia and Columbia-class submarines, Tomahawk missiles, vehicle-mounted laser range finders, Predator aerial vehicles, and Joint Direct Attack Munition smart bombs all demand massive amounts of REEs:

| Equipment | Rare earths used | Application examples |

|---|---|---|

| F-35 fighter jet | 418kg | Guided missiles, lasers for determining targets |

| Arleigh Burke DDG-51 Destroyer | 2,600kg | Advanced radar and missile-guidance systems, propulsion |

| Virginia-class submarine | 4,600kg | Tomahawk missiles, radar systems, drive motors |

Source: VC Elements

In 2010, Beijing first used REEs as a bargaining tool by restricting exports to Japan during a diplomatic dispute over the Diaoyu Islands. This alarmed Japan enough to prompt it to develop a five-pillar package reducing its dependence on Chinese rare earths from 90% to 60% – still high, but less concerning.

Western media portrays China as a monopolistic bully; China casts the rare-earth debate as a defensive struggle against external threats

In 2018 and again in 2023, the US military industry experienced similar shock following trade tensions with China. A People’s Daily commentary headlined 'United States, don’t underestimate China’s ability to strike back', acknowledged Beijing's power over REEs. 'Will rare earths become a counter-weapon for China to hit back against the pressure the United States has put on for no reason at all? The answer is no mystery.' This shows a different framing – while Western media portrays China as a monopolistic bully, China casts the rare-earth debate as a defensive struggle against external threats. The latest Chinese export restriction in April 2025, imposed in response to the tariff war, shows that bargaining tools remain unchanged.

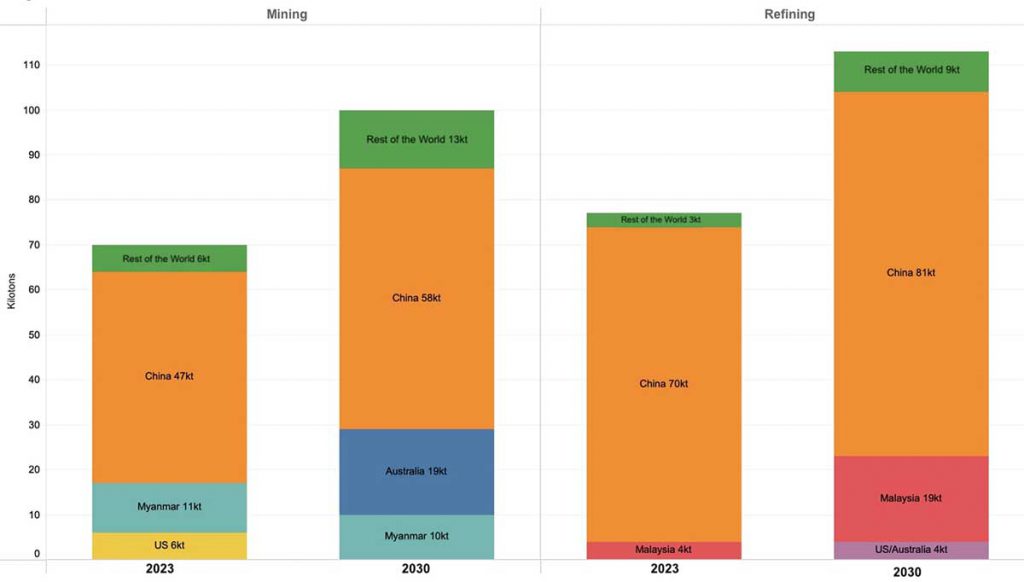

While debates over blame continue, the facts remain clear: between 2020 and 2023, 70% of US imports of rare earth compounds came from China; see the graph below. However, it was not until 2020 that the Department of Defense (now the Department of War) started investing in domestic supply chains, and 2024, that the National Defense Industrial Strategy identified reliance on foreign REE sources as a national security risk. The goal was to develop a domestic mine-to-magnet REE supply chain and commit substantial funding to meet all US defence needs by 2027.

Not until 2024 did the US begin to invest in domestic rare-earth supply chains. This leaves it heavily dependent on Chinese imports for many years to come

The US appears to be moving toward a subsidy-driven approach, similar to China’s strategy. Since then, the Pentagon has funded projects like MP Materials and Lynas USA, but output remains minimal compared with China's. While recent breakthroughs show promise, countries including Australia, Brazil, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Vietnam are investing in mining, processing, and research and development to diversify supply. International cooperation, such as Australia’s Critical Minerals Hub and Japan’s joint projects with Vietnam, will be key to building alternatives. However, large-scale production remains years away, leaving the US dependent on Beijing’s exports.

For the Trump administration, efforts to counter China’s export controls with tariffs, bans, and non-market strategies revealed the limited tools available to the US. China, meanwhile, has demonstrated how rare earths can be used to pressure not just defence contractors but also the automotive sector and broader technology supply chains. Export restrictions on neodymium magnets and heavy rare earths like terbium and dysprosium (pictured in the header image) highlight the choke points China can activate.

China can exploit its rare earth superiority to pressure defence contractors, the automotive sector, and broader tech supply chains

Simultaneously, while China uses rare earths as leverage, its own industries rely on US technology, advanced chips, aircraft engines, and access for Chinese students to American universities. During the Geneva talks, President Trump signalled he would ease some of these restrictions as a goodwill gesture if rare earth exports resumed. It seems like both powers are attempting to curb each other’s dominance by weaponising their own strengths, yet in doing so they reveal how deeply their leverage rests on mutual dependence.

Looking ahead, the scenarios diverge sharply. A swift US breakthrough in processing capacity is possible but unlikely within four to five years, meaning any attempt would confront the realities of time, cost, and scale. For now, Beijing’s monopoly ensures that rare earths remain its most reliable ace in a high-stakes geopolitical game. Still, in this deeply interdependent setting, ongoing bargaining is likely to compel both superpowers to temper their ambitions with pragmatic compromises.