The Brazilian parliament recently resumed debates on a reform proposal for public administration. Nayara Albrecht argues that although the proposal claims to target privileges, it risks undermining the integrity of public administration. She suggests that the agenda should also address disparities within the public sector

Brazil’s public administration reform – originally proposed in 2020 – has returned to the Brazilian parliamentary agenda. In 2021, drawing from a large body of research, I argued that the reform overlooked one of the central problems of Brazil's civil service: inequality among public employees. Years later, the 'new' proposal under discussion continues to overlook the core challenges facing public administration in Brazil.

The reform seeks to promote greater transparency through (supposedly) addressing so-called privileges. However, all proposals so far have avoided what really matters for building an efficient public service: stable, consolidated state career structures that encourage civil servants to dedicate themselves to policies that benefit the population rather than particularistic interests.

The 2020 proposal – frequently referenced in recent debates – aimed to dismantle the stability system, leaving civil servants vulnerable to political pressures from those in power. Furthermore, while it claims to target alleged privileges, the proposal fails to address key issues of efficiency in public administration, such as public sector inequality and the lack of transparent criteria for political appointments.

All reform all proposals so far have avoided what really matters for building an efficient public service: stable, consolidated state career structures

The debate is related to the political science and public administration literature on state personnel recruitment and the politicisation of public bureaucracy. Overall, this literature tends to associate politicisation and patronage with corruption. However, politics is inherent to public administration because, as Pedro Cavalcante highlights, bureaucrats play several political roles in policymaking.

The attack on job stability in Brazil's civil service – often raised by the guardians of efficiency – is controversial. While stability can lead to complacency, it also protects the public bureaucracy from capture by private interests. Raphael Machado and Alexandre Gomide demonstrate how stability improves the quality of public bureaucracy. Without tenure, civil servants would be subject to the political will of their superiors. Politics is an inevitable aspect of public administration, but bureaucracy often acts as a safeguard against harmful interests – and this resistance is only possible, above all, because of stability. Having a stable bureaucracy prevents anti-democratic governments from dismantling institutions entirely.

When advocates for reform speak of 'privileges', they usually assume a homogeneous system in which every civil servant earns a very high salary. This is not true in the Brazilian civil service.

Although public sector wages are, on average, higher than those in the private sector, state careers vary substantially in salaries and other benefits. Public sector monthly pay ranges from around 1,500 to 30,000 reais (USD $280–$5,600). Those in lower strata may struggle to make ends meet in the federal capital, Brasília, where prices are particularly high. Inequality is even more pronounced among the three branches of power, with some civil servants in the judiciary earning more than the legal limit.

The involvement of bureaucrats with politics is a core theme in public administration reforms. Several scholars – including Jan-Hinrik Meyer-Sahling and Patrik Öhberg – associate politicisation of the bureaucracy with the use of political criteria to the detriment of merit criteria in personnel policies. In debates on reform, discretionary posts and political appointments are often demonised and associated with corruption, patronage, and clientelism.

In scholarly debates on reform, discretionary posts and political appointments are often associated with corruption, patronage, and clientelism

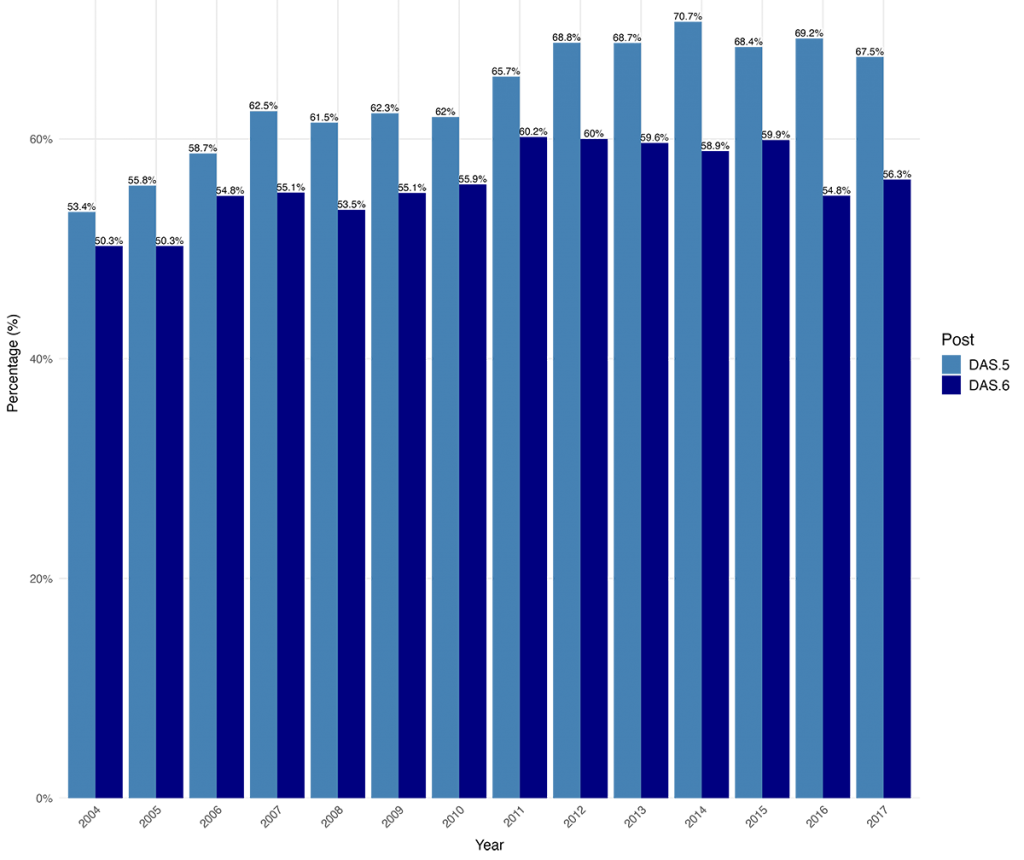

Yet the existence of such posts is not in itself the biggest problem. Most of these posts – formerly known as Direção e Assessoramento Superiores (DAS), now Cargos Comissionados Executivos (CCE) – have historically been occupied by career civil servants. This holds even for the highest office:

According to Quality of Government Institute data, Brazil has a highly professionalised bureaucracy compared to other Latin American countries. Politicisation and professionalisation are not, therefore, mutually exclusive.

By focusing on ending stability, discretionary appointments, and other such measures, the reform fails to address the real problems of the Brazilian system.

First, it is essential to confront inequality within the state itself. It is pointless to speak out against privileges while defending unrealistic salaries for certain positions – including those of the parliamentarians who advocate for the reform. Such discourse sounds hypocritical, since it is advanced precisely by those most privileged in the country's political system.

The real problem in Brazil’s public administration lies in the absence of clear criteria and oversight in appointments, and the lack of well-defined career paths

Second, attractive salaries are important to reduce civil service turnover and enhance bureaucratic performance. Well-defined and structured careers are fundamental.

Lastly, having a system of discretionary appointments is not inherently problematic in public administration, provided it is well designed.

The real problem in Brazil’s public administration lies in aspects often overlooked by reform proposals: the absence of clear criteria and oversight in appointments, the lack of well-defined and standardised career paths in some public bodies, and the absence of a formal and efficient system of performance evaluation. Yet, once again, reform advocates appear too busy chasing the wrong suspects. In doing so, they are missing genuine opportunities to strengthen the Brazilian civil service.