The row in the White House between Presidents Trump and Zelenskyy shocked the world, and threatens the transatlantic alliance between the US and Europe. However, Paul Whiteley argues that Trump may be unwittingly creating a situation which will see the United States weaker and more isolated in the long term

The row between Presidents Trump and Zelenskyy in the White House reached a hight point with Trump’s accusation that Zelenskyy was risking ‘World War Three.’ Trump subsequently reinforced this with an abrupt decision to cut off arms supplies and access to intelligence to the Ukrainians.

In this display of power, however, Trump may be overplaying his hand. A new ‘power scale’ designed to measure the power resources of nations suggests that Trump is fanning the flames of war by alienating his traditional allies and so weakening the US in the long run.

The background to this is the change in the relationship between the US and China. At the turn of this century, the US was dominant, but a bipolar system has now developed. War in Ukraine has strengthened the so-called ‘axis of resistance’ made up of Russia, China, North Korea and Iran. At the same time, Trump’s behaviour is weakening NATO.

To plot the change we can analyse the power resources available to both sides. Most scholars measure power in terms of resources, specifically wealth and military assets. The logic of this approach is simple: countries with more wealth and more military assets tend to win over countries with fewer such resources.

There are different views about what we should measure when measuring power. Two obvious indicators are population size and GDP. Total GDP of the United States in 2023 was about $22 trillion with a population of 335 million. In China, it was just over $17 trillion with a population of 1.4 billion.

But population and GDP measure only resource capacities, not the ‘hard power’ of military capabilities and defence spending. Alongside resources and military might, we need to measure ‘soft power’, including overseas aid, cultural influences and, most importantly, capacity for technical innovation.

Power must be measured by cultural influence and capacity for technical innovation, as well as by wealth and military assets

A simple and robust measure of power includes four variables: population size, GDP, spending on defence; and the number of patents taken out by a country each year. Patents registered is a measure of technical innovation that is becoming increasingly important, especially in relation to warfare.

The power scale is created using data averaged over the period 2015 to 2022 from the World Development Index together with the Stockholm Institute of Peace Research. These sources provide four measures which combine into a strong unified power scale, calculated for 124 countries. The scale uses data over a seven-year period prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, to get a robust measure, not affected by the war.

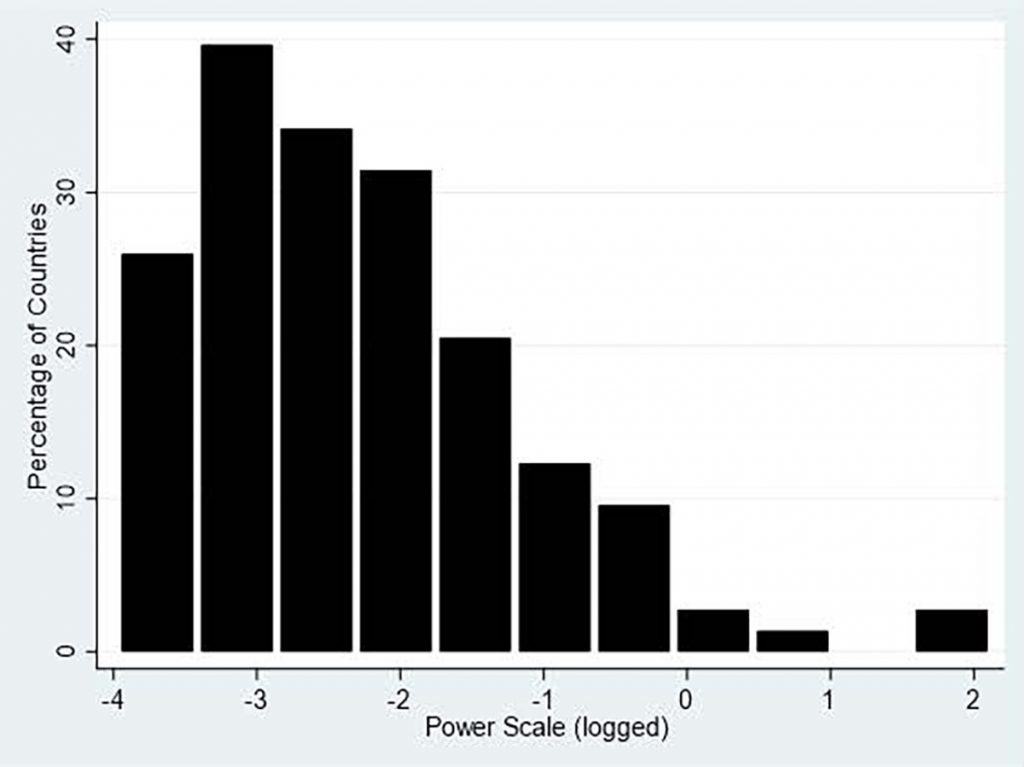

This graph shows how the power scale is distributed across the 124 countries. A negative score means a country is weak; a positive score the opposite. The scale is measured in logarithms to make it easier to interpret. It shows how power resources are unequally distributed across the world when they are measured in this way. The countries on the right-hand side with the strongest power index scores are China and the United States.

There are limitations in measuring power in this way. For one, the scale does not capture the extent to which countries are mobilised to fight a war at any particular time. If it were updated to 2025, it would show that Russia has moved up since 2022. One Poland-based think tank shows that in 2025, Russia will devote 43% of state spending to defence and internal security.

Ukraine is battling for its very existence, while Russia is fighting a war driven by Putin's imperialist dreams

A second problem relates to the efficiency with which a country can fight a war. Ukraine is outclassed in terms of resources, but it is fighting for its very existence and has shown remarkable resilience. In contrast, Russia is fighting an imperialist war driven by Putin’s dream of recovering great power status, and he has achieved only a stalemate. The casualty reports from the drone and missile attacks on Ukraine, though tragic, are minuscule compared with the thousands of deaths from carpet bombing in the Second World War. The Russians will not be able to bomb their way to victory.

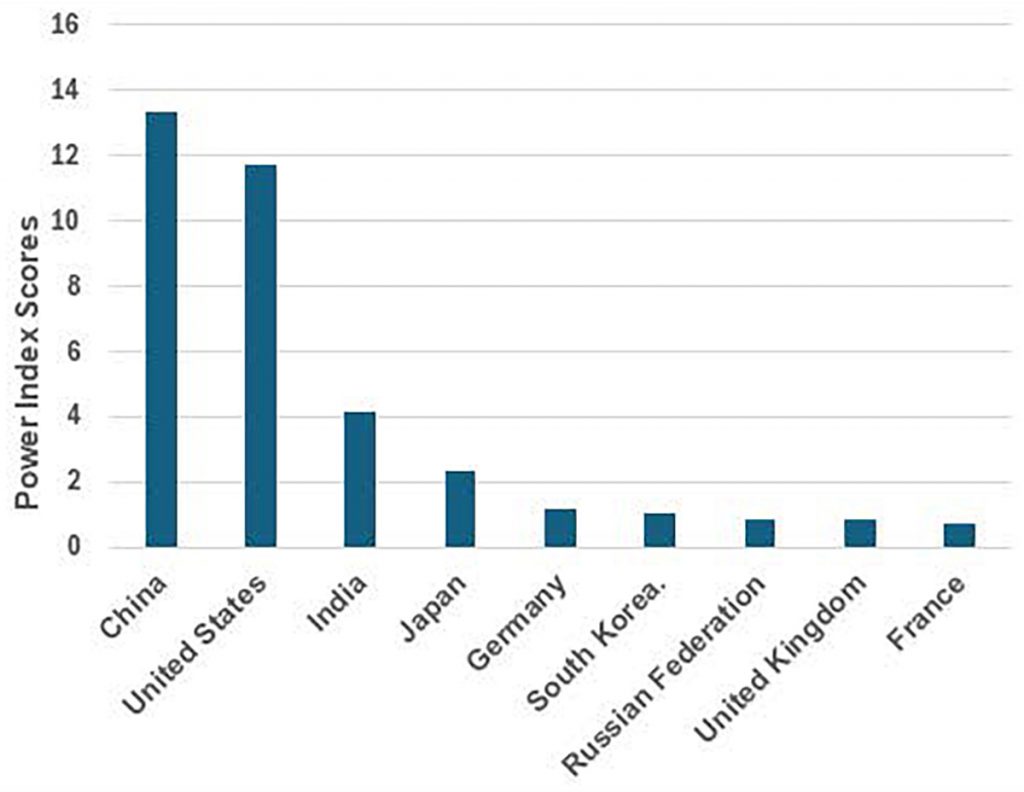

The figure below shows the top ten countries measured on the power scale. Contrary to expectations, the ‘top tier’ countries if we measure power this way are China first and the US second. After them (and at a considerable distance), India and Japan are ‘second tier’ countries. The five 'third tier' countries are Germany, South Korea, Russia, the UK and France.

The scale highlights two key points. First, if major European nations pool their power resources, they easily exceed those of Russia. Indeed, Russia's armed forces have been degraded by massive losses since the start of the war. UK intelligence estimates that Russia’s losses could reach one million by summer of this year. Thus, if it acts rapidly, Europe could fill the military gap left by the United States.

Russian armed forces are massively degraded. If European nations pool power resources, they easily exceed Russia's

The second point is that the real enemy of the United States is not Russia, which is relatively weak, but China. However, if Trump succeeds in weakening NATO and continues to alienate longstanding allies in Europe and around the world, it invites Chinese aggression. Chinese leader Xi Jinping has stated his aim of invading Taiwan, possibly by 2027.

Given this, Trump may well find himself fighting another war of aggression alone without the US’s traditional allies. This time, he will face a much more formidable enemy.