Courtney Blackington and Frances Cayton argue that populist politicians tend to dog-whistle conspiracy theories when speaking to general audiences, but explicitly endorse them when speaking to supporters. Thus, politicians strategically invoke conspiracy theories to avoid pushback, while still managing to rally their core supporter base

Populist politicians often deploy conspiracy theories (CTs) to rally their base or earn electoral support. However, spreading CTs alienates moderates. Of course, conspiracy theory beliefs do not necessarily correlate with political ideology. But CTs do tend to appeal more to extremists and to those who are strongly partisan.

To address this dilemma, our recent article in Government and Opposition theorises that populists are more likely to dog-whistle CTs when addressing general audiences, but when speaking to faithful supporters, they often explicitly endorse CTs. Dog-whistles use coded language to project two messages: a veiled message for fellow activists and a seemingly moderate message for the general public. This rhetoric may allow populists to mobilise strong partisans without losing moderates.

Politicians use dog-whistles to convey a veiled message for fellow activists and a seemingly moderate message for the general public

However, dog-whistling is not a foolproof strategy. If populists repeatedly dog-whistle CTs, mainstream audiences may learn these messages, and the dog-whistle may lose its veiling power. We theorise that as populist politicians use dog-whistles more often, the message will ‘mainstream.’ When mainstreaming occurs, we predict the incentives for populist politicians to explicitly endorse CTs increase, while the incentives to dog-whistle decrease.

We test our theory by analysing reactions to the Smoleńsk plane crash. The crash generated long-standing, politically salient CTs, which enable us to analyse changes in politicians’ discursive strategies.

On 10 April 2010, an aircraft containing 96 people – most of whom were Polish officials – flew to attend the commemoration of a 1940 massacre of over 21,000 Polish military officers and intelligentsia. En route, the plane crashed, killing everyone on board. Most of the deceased politicians were affiliated with the populist Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) party.

Despite official investigations indicating that the crash occurred as a result of thick fog, pilot error, and poor visibility during the plane’s descent, CTs quickly emerged claiming that explosions caused the crash.

PiS officials have, since then, dog-whistled and explicitly endorsed crash CTs. On the annual anniversary, crash discussions occur offline at commemoration marches and online on social media. These street marches and online discussions involve two very different groups of people.

Offline, PiS officials participate in, fund, and organise marches to commemorate crash victims, with several thousand participants in attendance. Marches attract strong party supporters and ‘true believers’ in CTs, who devote substantial time and resources to attend.

Online, the readership of PiS social media posts is more diverse, and not necessarily affiliated with PiS. Polish social media users are disproportionately female (56%), young (93% are 18–29), and urban (68% live in cities of more than 250,000 inhabitants). All this correlates with support for PiS' main opposition party, Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform).

We hypothesise that PiS officials will be more likely to dog-whistle CTs on social media, but explicitly endorse CTs at marches. Over time, we expect PiS officials to explicitly endorse CTs more and to dog-whistle less.

We created an original dataset of the speeches of PiS party leader Jarosław Kaczyński at the 10 April commemoration events from 2012–2019 and 2022 (events were cancelled during the pandemic). In addition, we analysed every 10 April tweet from the official PiS Twitter account from 2010–2022.

We analysed our data using structural topic models. To identify the most prevalent themes across mediums, we show the words with the greatest probability of being associated with a given topic in the speech corpus (the first table) and in the tweet corpus (the second table).

Offline, over 69% of speech discourse promotes conspiracy theories about the Smoleńsk air disaster, in contrast with only 12% of online content

Offline, over 69% of speech discourse promotes crash CTs. Over 33% of the speech corpus includes explicit conspiratorial endorsements. Conspiratorial claims of a need to reevaluate the ‘crime’ or to find the ‘truth’ comprise another 22% of the speech corpus. 13.8% of the discourse describes the crash as an ‘evil attack.’

In contrast, online, only 12% of the corpus invokes CTs by appealing to the need for the ‘truth.’ About a quarter of discourse leverages dog-whistles, tying those who died in the crash to those who died during the 1940 Katyń massacre.

Thus, PiS invokes more explicit CT endorsements when addressing its base, but dog-whistles to broader audiences.

| Topic | Proportion | Topic keywords | Topic discussion |

| Crash activism | 33.21% | abov-, hard, imposs-, worth, everyon-, real, action, organ-, marek, ani, tomasz, gazeta, polska | Organisers of monthly events are mentioned |

| Conspiracy theory / investigation | 22.06% | respons-, administ-, advantag, drop, pursu-, spoke, true, care, establish, week, discuss, crime, accid-, mobil-, mind | The need to find and speak of the crash's 'true' causes are mentioned |

| Memorialisation | 16.80% | signific-, terribl-, unit-, path, memori-, presid-, determin-, import-, win, relat-, moral, includ-, whi-, faith | Words remind of the significant and terrible loss of lives |

| National unity | 14.09% | win, follow, refer, destroy, overcom, poland, rememb, day | Words call for national unity in remembering and overcoming the crash as well as destroying those responsible for it |

| Conspiracy theory general | 13.84% | attack, evil, activ-, overcom- | References to an evil attack or activity that can be overcome invoke conspiracy theories |

| Topic | Proportion | Topic keywords | Topic discussion |

| Memorialisation | 32.97% | anniversari-, kaczyński, disast-, lech, laid, presid-, prime, we, march, ministr-, speech | Words reference monthly commemoration events, crash victims or those involved in commemoration events |

| Katyń memory | 24.18% | rememb-, pis, monument, dure, flower, @tvpinfo, katyn, media, politician | Words link Katyń to Smoleńsk and indicate actions and media coverage of commemorations |

| Broadcast details | 19.68% | April, poland, somlensk, broadcast, republ-, late, pis, victim, @morawiecki, plaqu-, pole | Words share broadcast coverage of commemoration events, as well as participants |

| Kaczyński speeches | 12.30% | #10, rt, tribut-, dariusz, michal oweski, grave, rememb-, @beataszydlo, deputi-, photo, wife, appeal | Words summarise Jarosłav Kaczyński's speeches with mentions of crash victims and thanks to crash activists and participants |

| Conspiracy theories | 10.87% | celebr-, kaczynski, @szefernak-, wreath, truth, memori, jaroslaw | Words pair commemoration events with conspiratorial calls for truth, and references to a conspiratorial PiS politician |

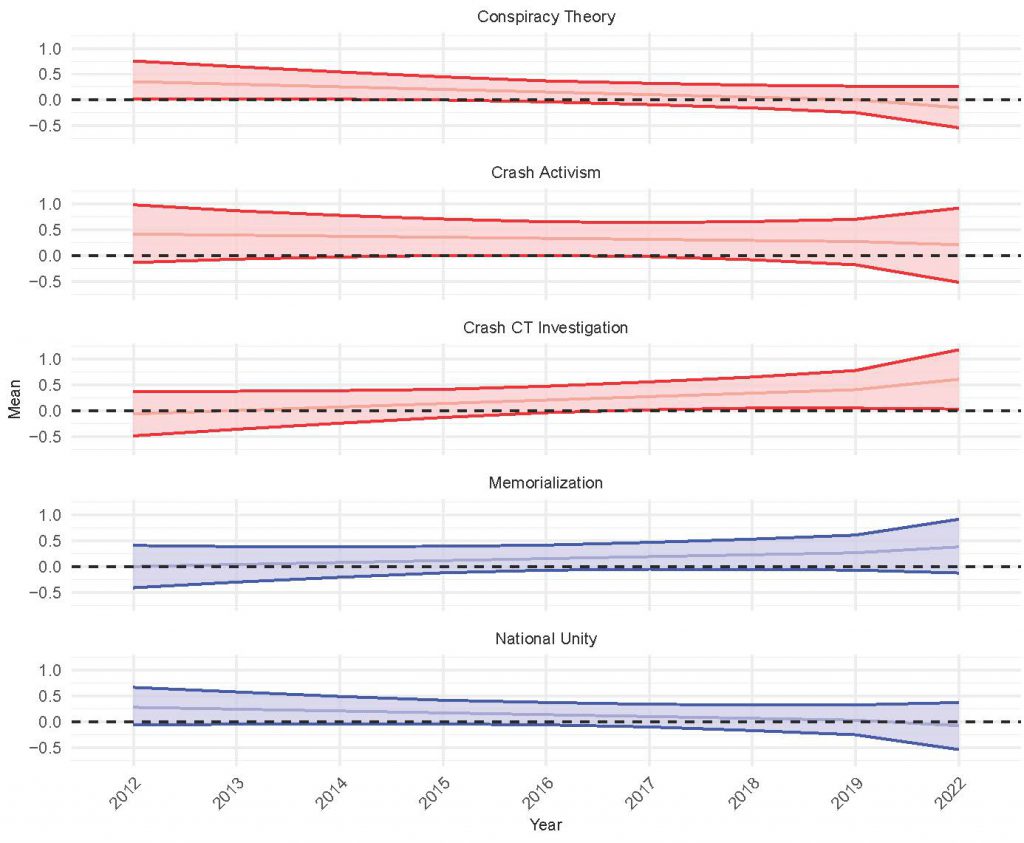

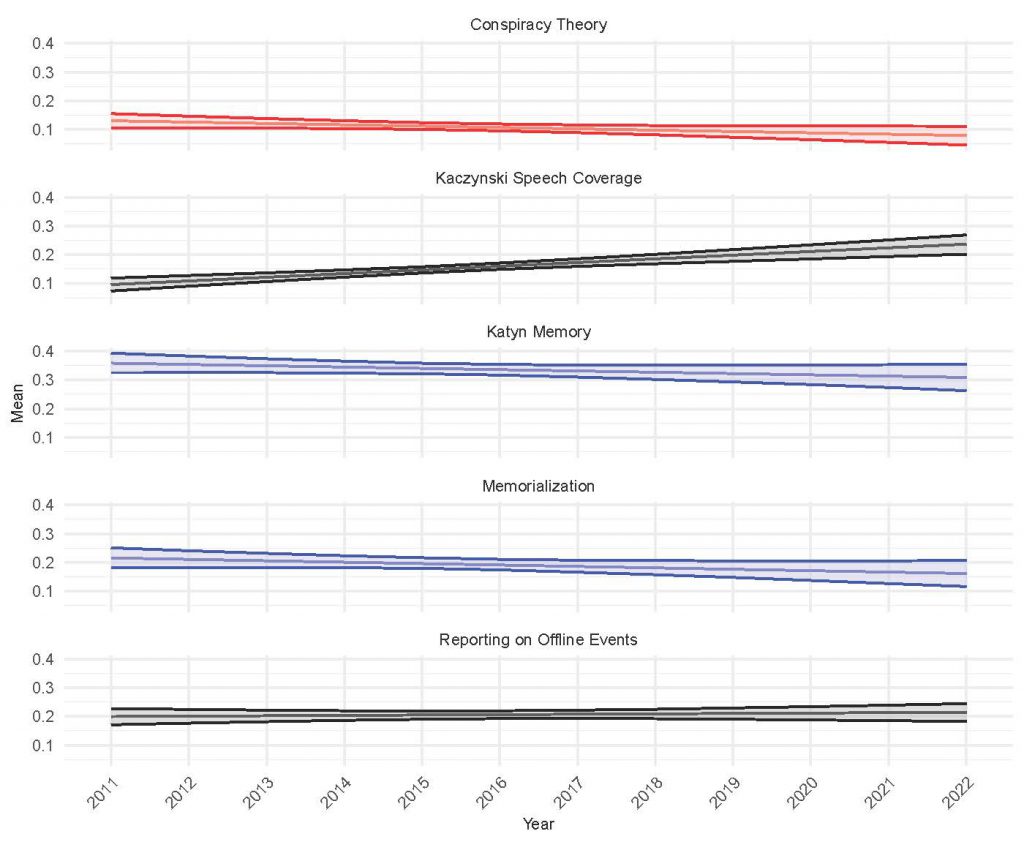

Does the mainstreaming of conspiratorial discourse shape PiS discursive strategy? We generate the expected proportion of the corpus that comprises conspiratorial versus non-conspiratorial topics over time. In the graphs below, red topics show CT appeals, blue topics represent dog-whistles, and black topics focus on programmatic or logistical information.

Speech analysis suggests that explicit CT appeals and dog-whistles oscillate in frequency at commemoration marches, though conspiratorial discourse slowly increases. Analysis of topic proportions on Twitter shows that CT rhetoric is lower among general audiences.

Together, the graphs indicates that, over time, the confidence intervals for explicit conspiratorial rhetoric and dog-whistles increase. PiS officials increasingly combine dog-whistles with explicit CT endorsements. When dog-whistles become familiar, the utility of distinguishing communication strategies by target audiences may decrease.

Thus, by analysing online and offline discussions of the Smoleńsk CT, we offer preliminary evidence that politicians may respond to the mainstreaming of dog-whistles over time.

By intertwining dog-whistles with explicit references to conspiracy theories, politicians can train conspiracy theorists to recognise doublespeak across various contexts

These findings suggest that by intertwining dog-whistles with explicit CT references, politicians can train CT believers to recognise doublespeak across various contexts.

Our study shows that the nature of the audience can affect how politicians spread CTs. We also advance understandings of how online and offline conversations differ when it comes to the study of CTs. Our findings also shed light on the relationship between populist rule and CTs by detailing how political leaders may differentiate their conspiratorial discourse according to their target audience.