Political purges are dramatic, yet common, events in dictatorships. Sometimes bloody and very consequential. By dissecting the sequence of decisions behind these events, Austin S. Matthews shows that the way a dictator goes about a purge can determine outcomes like regime survival and risk of a coup

Hager Ali’s inaugural post in this series rightfully argues that the study of regime variance in dictatorships lacks important conceptual nuance. As a result of this, we may misattribute important causal mechanisms behind regime actions, among other issues. I contend that our definitions of repressive tools in dictatorships also suffer from weak conceptual framing. Without a clear understanding of autocratic decision-making, we may misjudge how different tools of repression affect outcomes like autocratic survival.

Political purges as a concept illustrate this critique. Like regime types, their conceptualisations have been hazy and often over-generalised. Political purging involves the removal of a dictator’s enemies from positions of influence within the regime. It marginalises potential rivals to ensure the dictator’s continued survival in power. Over recent years, the literature on purges has grown, with research on targets, motivations, and timing of these critical insider contests.

However, despite recognising the importance of purges to autocrat survival, the literature still does not agree on what constitutes an actual political purge. Some authors suggest purges need to end in jailing or killing of their targets to be consequential. Others argue that dictators can purge non-violently, which expands the definition of purges to include dismissals and demotions.

Recent studies suggest that the literature has neglected how a purge can take various methodological forms, rather than being a single uniform process. Some in the field have acknowledged differences in the scopes of purges. However, we still need to better assess the actual sequence of the purge.

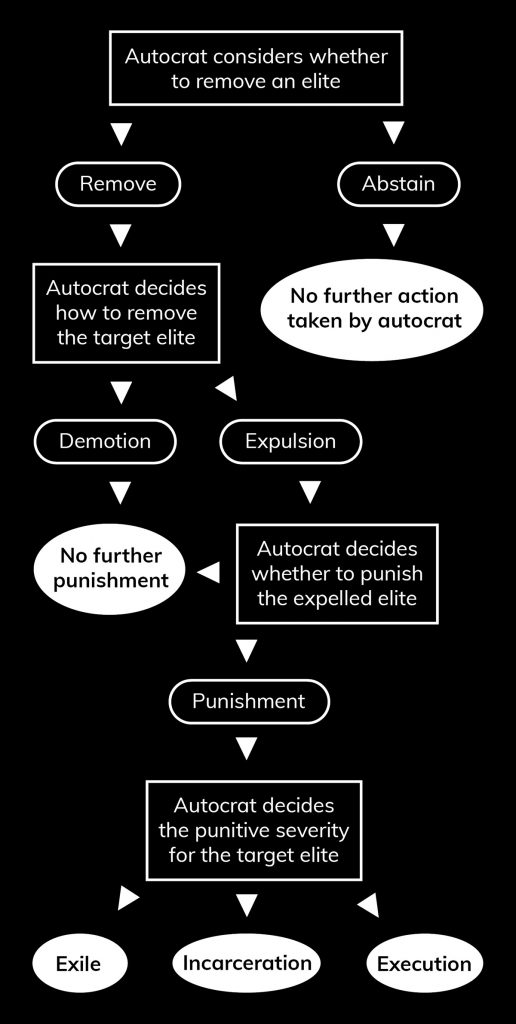

I suggest a new sequential understanding of political purges. This visualises these events as the culmination of two decisions by the dictator. After a dictator selects a target and decides to move forward, they will weigh the costs and benefits in certain methods of purging. All potential choices in this sequence fit within the broad definition of ‘purge’. However, the impact of these different choices may be great, for both target and perpetrator.

A political purge should be understood sequentially, as the culmination of two decisions by the dictator: the method of removal and the fate of the victim

Once a target is identified and a purge selected as the method of their repression, the dictator decides how far their target should be marginalised. The purge is the culmination of a two-step sequence that starts with institutional removal and ends with a decision about its target's personal fate.

In the removal phase, dictators have two choices on how severely the target will be marginalised from the regime. Some will only remove a target through demotion. They are separated from the decision-making bodies of the regime, but still permitted to remain in lower-level offices. The low-intensity nature of this choice makes it more of a ‘soft’ removal, often routinised and less conflict-intensive.

Other targets may suffer a steeper fall through a purge by expulsion. Expulsion constitutes a stronger form of purge because it ensures the complete separation of the target from the regime at all levels and renders them an outsider. Targets are completely removed from all posts that potentially give them access to power or influence in the regime, even positions that have less decision-making authority. This is more reflective of the adversarial purge concept used across the literature.

If a dictator merely demotes their target, they can continue to serve the regime. They suffer no more than the humiliation of their fall from such lofty heights. But if the target is put through the expulsion process, they are subject to potential punitive action by the dictator before the conclusion of their personal ‘purge.’

For some targets, expulsion may be enough to ensure they are no longer a threat to the dictator’s survival. The dictator has made them an example by orchestrating their expulsion, and this downfall may be punishment enough. The sequence ends without further action, leaving the target with their life and freedom, sentenced only to live in obscurity.

Some dictators, however, may choose a more severe end to the purge sequence, and have the target punished with violence. Their potential to harm the dictator’s survival as a rival is snuffed out in some way. This could take the form of isolating them from potential allies through exile, incarceration, or execution.

We usually see political purges analysed with reference to their outcome, but not all purges are accomplished through the same sequence of events. Some are more severe than others in how they marginalise the target and the level of punishment meted out. Understanding the purge event as the outcome of a sequence of choices could help us to better understand their secondary outcomes, such as coups or popular uprisings.

How a dictator purges can determine elite and public perception of the dictator’s threat profile, and thus influence secondary outcomes such as coup risks or popular resistance

How a dictator purges can determine elite and public perception of the dictator’s threat profile. A purge involving executions may signal strength. But it may also alarm surviving elites, who fear they will be next on the executioner’s block. Dictators who only demote their rivals, however, may be seen as less of a personal risk to elites who recognise that punishment has been withheld. Some may also see clemency as a sign of weakness.

Scholars should consider how autocratic regimes and leaders carry out purges more carefully, rather than merely whether they do so. Closer attention to the methods in the removal and fates of purge targets may bring new insights into authoritarian politics. Doing so will grant the discipline a more precise vision not only of how dictators use repressive tools, but also how the variation in these tools may affect consequential outcomes such as autocrat and even regime survival.

I am not a political science student - more on the economics side - but I find this article very interesting. It goes some way to answering the fundamental question of how dictators/dictatorships are formed. If we are able to analyze the risks of dictatorship, I believe we can stop it or reduce its impact.

Dictatorship is commonly known in government. Rest assured, it exists everywhere - in the family, in the civil service (recent events in the UK are good examples), in schools (bullies are forms of dictators), in hospitals, and in NGOs/civil societies, to name but a few.

In politics, dictatorship is formed often in either of two ways - by a military coup d'etat or by a self-coup in which elected leaders make their rule permanent by modifying or suspending constitutions or simply interpreting the rules and regulations to their advantage.

However, I would argue that we (society) make dictators. Let's take an organization that is run by a board of governors with a board chair and all other designations. Every time, the board chair submits motions (mostly good ones for the organization), members accept without opposition or at least modifications. When this is repeated oftentimes, the board chair develops a mindset that whatever she/he says is accepted - dictatorship is a mindset!

Second, certain members of the board are frequently absent from meetings, and board meetings are often held with the minimum quorum achievable. This leads to important decisions being made by a small group without the benefits of opinions from the regular absentees. This creates division in the board and small group dominance arises.

The way to stop dictatorship or reduce its impact is by active participation and analysis of the signs and symptoms (risks) of dictatorship. If we (society) are careless (let alone submissive), individuals and small groups will use that to their advantage and become dictators. I rest my case!