Turkey is upping its game in terms of exercising ‘pastoral power’ over its diaspora communities abroad, aiming to turn them into loyal and disciplined subjects who accept the government’s nationalist discourse, writes Chiara Maritato

Turkey has been in the spotlight as one of those 'origin' or 'sending' states that export imams and preachers to serve ‘their’ Muslim communities living abroad. The contribution of religious officers in diaspora-making is a practice that has plenty of historical antecedents.

The Scalabrinian Missionaries of Saint Charles were founded in 1887 to maintain the Catholic faith and practice among Italian emigrants in the New World. The Irish Catholic Church performs the same function for the Irish diaspora. These are just two examples that testify to how the relations between home countries, religious hierarchies and emigrants intertwine.

However, the main peculiarity of the Turkish case is that the religious officers who are sent to serve diaspora communities are state employees hired by a Turkish state agency (Diyanet Işleri Başkanliği, hereinafter Diyanet).

The Diyanet has acted as a domestic and foreign policy instrument for the diffusion of national identity and the role of religion in the Turkish polity

The Diyanet, founded in 1924 and charged with the management and control of the Turkish interpretation of Sunni Hanefi Islam, has acted as an instrument of both domestic and foreign policy as it pertains to the diffusion of national identity and the role of religion in the Turkish polity.

Since the 1970s, the Turkish state has used imams and preachers to propagate the State’s religious-nationalist ideology while treating the diaspora as a political, cultural and social project.

Between the 1980s and 1990s, Diyanet’s grip on international affairs intensified, notably via the establishment of the Department for International Relations (in 1985) and the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB) in Germany (1984).

Over the same period, the activities of religious officers became an integral part of a set of measures designed to contain and control the activities of refugees and asylum seekers, particularly Kurds, who had migrated from Turkey to Europe, together with members of outlawed political and religious organisations.

With the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) to power in the early 2000s, this long-lasting engagement was, over time, transformed. Over the past two decades, state agencies such as the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), the Presidency for Turks abroad and Related Communities (YTB), and non-formal institutions or GONGOs like the Union of International Democrats and the Maarif foundation, have been directed towards diasporic communities.

While involving different actors and institutions, such engagement has developed in that grey zone between diaspora, soft power and foreign policy, designed with the intent to defend emigrants' rights against discrimination, reinforce their ties with the homeland, and widen Turkey’s conceptions of citizenship belonging and identity.

policies and institutions aimed at producing legal, socio-cultural, economic and political links with diaspora communities reveal an art of governing which extends beyond the homeland

What has been depicted as the Turkish state’s more ‘empathetic’ narrative towards its citizens abroad is, at the same time, symptomatic of a significant change in ‘governmentality’.

According to Foucault, governmentality defines the instruments by which a population is rendered governable through a set of governmental apparatuses and knowledge. The policies and institutions aimed at producing legal, socio-cultural, economic and political links with diaspora communities reveal an art of governing which extends beyond the homeland. But how do these current governmental techniques operate at micro level?

Albeit in continuity with past strategies geared towards building loyal and enduring relations with emigrants, Diyanet’s current international mission has expanded in scope and scale. Religious services have been institutionalised to reach as many people as possible, including women and children.

Activities are conducted in a standardised way under the direction of religious attachés (din ataşesi) working in Turkish embassies and consulates. Imams and preachers serve abroad for a maximum of five years, and their daily engagement goes beyond ad hoc spiritual guidance or sporadic official celebrations. Their role could be described as holistic pastoral care, available on demand and designed to enlighten the believer about any aspects of life.

This transformation has brought the Diyanet’s religious services closer to the Christian 'pastorate,' a notion that recurs in the institution’s recent publications and lays the groundwork for spiritual guidance designed as 'religious counselling'. Combining psychology, theology, guidance, and counselling, the Diyanet services to Turkey-originated communities living abroad comprise education about religion and morality as well as spiritual guidance.

The Diyanet has emerged as a key institution through which Turkey acts as a caregiver and a (religious) services provider that paternalistically embraces its dispersed communities. But its development also shows how pastoral power (what Foucault defines as a 'form of governmentality exercised over men') is exerted over diaspora communities.

The Diyanet has emerged as a key institution through which Turkey acts as a caregiver and a (religious) services provider that paternalistically embraces its dispersed communities

Diyanet officers' pastoral services are manifested in a wide range of socio-cultural religious practices that include religious classes on the basic principles of Islam, seminars on topics related to family issues, and social activities.

Diyanet exercises a form of pastoral power which involves a mix of care and control combining religion and Turkish national symbols such as the commemoration of martyrs, and the Battle of Gallipoli, as well as love for the motherland and respect for the Turkish flag.

As part of the home state’s paternalistic mission to propagate the government’s nationalist discourse abroad while forging diaspora communities as loyal and disciplined subjects, there is a focus on 'Turkishness' as an essentialised ‘sense of belonging’, embodying a form of patriotic loyalty which allows no place for hybridity.

This attempt to remap the boundaries of a Turkish and Muslim belonging in essentialist terms primarily targets individuals who share the AKP’s religious nationalistic outlook. It is a mission that speaks volumes about how the Turkish government values and imagines its nationalism beyond the country’s borders.

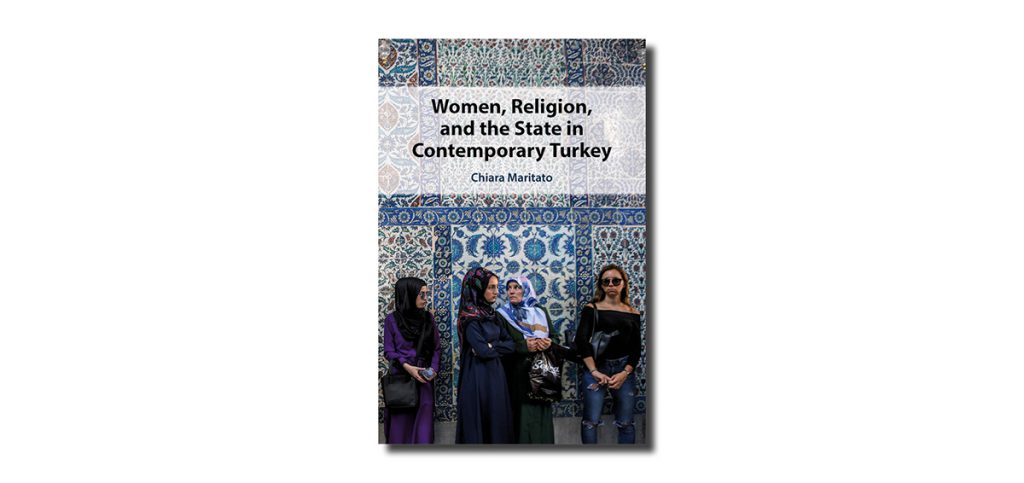

Chiara Maritato is the author of Women, Religion and the State in Contemporary Turkey, published in 2020 by Cambridge University Press