The Italian President has invited Mario Draghi to form the next government. It is the fourth time since 1994 that Italy has resorted to a technician to get itself out of a hole dug by the parties’ failure to agree on a government. This, argues Martin Bull, has connotations that go beyond the current crisis, representing a damning indictment of Italy’s model of party government

On the evening of 2 February 2021 the Italian President, Sergio Mattarella, announced he was appointing Mario Draghi (ex-Director of the European Central Bank and ex-Governor of the Bank of Italy) to form a government to replace what was the second government of Giuseppe Conte. Conte had resigned in early January following the withdrawal of the support of one its parties (Matteo Renzi’s ‘Italy Alive’), and an attempt to construct a third Conte government then failed over disagreements on the distribution of ministries.

In this situation, the President, exasperated at the failure of the parties, aware of the huge challenges facing the country, and reluctant to plunge the country into a lengthy election campaign which would bring an effective pause to governance, quickly ended the search for a political government and resorted to a technician – the fourth occasion an Italian President has done so since 1994.

'Super Mario' Draghi, renowned for allegedly saving the Euro during his stint as Director of the European Central Bank, fits the mould. His predecessors – Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (1993–94), Lamberto Dini (1995–96), Mario Monti (2011–13) – all came from distinguished economic professions or positions, were appointed during a crisis where the parties could not agree, received the personal stamp of presidential authority, and their governments were usually of short-term duration either to carry through specific reforms or run the country until the next scheduled elections.

‘Super Mario’ is renowned for allegedly saving the Euro during his stint as Director of the European Central Bank

‘Technical’ governments, however, are also dependent on majority support in parliament, starting with a vote of confidence. Draghi must therefore go through the same process of consultation and negotiation as any political appointment. The advantage technicians have is that the parties are aware that their own ‘mission’ has failed, that the President will not dissolve the parliament and call elections, and that therefore both he and the Italian people expect them to act in the national interest.

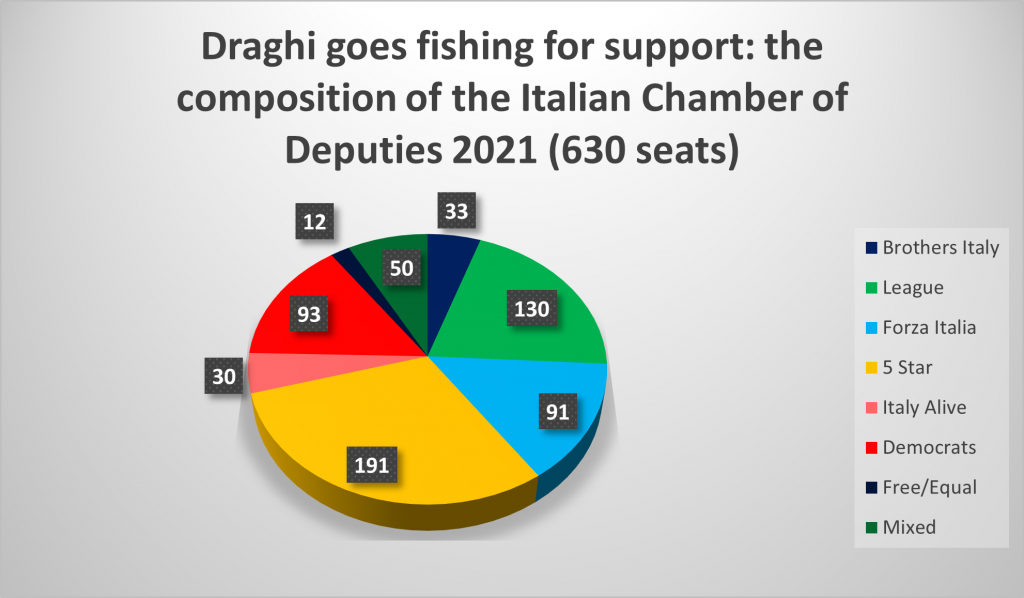

But can Draghi find the numbers? The initial indications (from preliminary consultations) look positive. His main problem is that there has never been a technical government without the support of the party of the relative majority, in this case the Five Star Movement, which has long railed against technical governments in principle. And many of its members identify Draghi as part of the European elite that placed Italy under the EU’s economic tutelage in the past decade. Yet, Five Star knows that a political government is now off the table, and that it would look irresponsible to adopt a position of opposition. So, despite turmoil inside the party and mixed signals coming from the leadership, there remains hope that Five Star will decide to swing behind Draghi.

the majority Five Star Movement has long railed against technical governments – in principle

The other parties of the outgoing centre-left government (Democrats, ‘Italy Alive’, ‘Free and Equal’) are all positive, and Conte himself has declared his support for such a solution. From the centre-right, Berlusconi (leader of ‘Forza Italia’) has indicated that it is the right option, and even Matteo Salvini’s League has indicated that he is not opposed in principle to a Draghi government, depending on the programme. So far, only the far right ‘Brothers of Italy’ have indicated that they do not approve of this technical solution.

Yet, there is some way still to go. In Italy, when parties offer their support in principle and make it dependent upon discussions about the ‘programme’, this is usually code for how many ministries they can secure – in what will be a reduced offering since several of them will go to independents. Much, then, will depend on Draghi’s negotiating skills.

In all of this, there is one factor that makes this specific situation unusual, despite the precedents. President Mattarella enters his ‘white semester’ (the last six months of his presidency) in July 2021, during which, by Article 88 of the Constitution, he is not allowed to dissolve the Parliament and call elections. By the time a new President is elected in February 2022, there will be little over a year left of the legislature, with elections due in March 2023.

Mattarella has said that he wants a government that does not identify with any single political force

What that suggests is that Mattarella is thinking of Draghi as the person to take Italy through a full two years to the end of the legislature. Mattarella has already laid out the key challenges facing Italy at this time: management of the pandemic, rollout of the vaccine programme, measures to address the economic fallout from the pandemic including, first and foremost, completion of Italy’s economic recovery plan, without which it will not receive its share of the EU’s Covid-19 support programme. And he has said that he wants a government that does not identify with any single political force.

Whether this is called ‘technical’, ‘technical-political’, ‘institutional’, ‘Presidential’, ‘independent’ or a ‘government of national unity’, the outcome will be the same: another government led by a non-political Prime Minister. And were Draghi to succeed both in forming a government and then remaining in office until the next scheduled elections, it would mean that Italy’s most important political office, that of Prime Minister, will have been held, for the entire 18th legislature, by independents. For Conte himself (a lawyer) ran two governments as an independent without membership of, or formal ties to, any political party.

This would not only be a damning indictment of Italy’s party system. It would also raise the question of whether, in view of their consistent failure to fulfil one of their key functions (producing ‘party government’), Italy’s political parties are any longer fit for purpose.