Global relations are increasingly regulated by states which strengthen control over their national territory. But delegitimation of neoliberalism does not signal the end of the global order or capitalism, says Kees Terlouw. It simply marks another shift between ‘relational’ and ‘territorial’ perspectives on legitimacy

Trust in market forces has dramatically declined in recent years. An avalanche of global financial, climate, Covid, and geopolitical crises, together with national political crises over inequality, identities, and populism, have undermined the legitimacy of neoliberal economic policies. The once widely accepted claim that there is no alternative to global markets has been replaced by a quest for alternatives to neoliberal policies.

The growing agreement that neoliberalism no longer gives adequate solutions to our current problems coincides with an increasing polarisation about successors

The growing agreement that neoliberalism no longer gives adequate solutions to our current problems coincides with an increasing polarisation about its successors. These broadly coalesce around a cosmopolitan urban bloc and a parochialist bloc. The cosmopolitans, using a relational perspective, propose to solve the problems generated by economic neoliberalism by deepening political globalisation and expanding global relations. For instance, they suggest strengthening global governance to control climate change and to promote human rights.

Parochialists, on the other hand, argue from the territorial perspective. They focus on protecting the identity and sovereignty of established communities at the local, regional, and national levels. They want to defend their territories against unwanted outside influences and interference, homogenise their territory and distribute welfare within it.

Both perspectives de-legitimise neoliberal policies. The cosmopolitan one does so by strengthening global governance; the parochialist by bringing all global relations under territorial control.

Relational and territorial perspectives have their roots in fundamentally different moral systems. The differences between these two perspectives on legitimacy are not new; they are deeply entrenched. However, it is important to examine their differences to better understand the crisis of neoliberalism and the related polarising political debates on populism.

Jonathan Haidt believes that the distinction between moral systems can be attributed to genetic differences in how people react to unfamiliar situations. Some regard unfamiliar situations as threats which must be controlled. Others are more enterprising and welcome them as an opportunity ripe for exploitation. Jane Jacobs, similarly, distinguishes between two systems of survival. The 'guardian' focuses on territorial protection, while the 'commercial' focuses on profiting from relations. At their heart are two very different views on legitimacy.

The table below gives a condensed version of these differences based on a typology I developed in more detail in my book Political Geography of Cities and Regions.

| Dimension | Element | Territorial | Relational |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional framework | Spatial form | Single, bounded stable territory | Multiple, open, flexible, purposive, overlapping networks |

| Organisation | Institutionalised authority and regulation | Specific temporary enterprises | |

| Coordination | Hierarchy delegates fixed competences | Cooperation based on interests and commitment | |

| Consent | Agreement | Contract, past elections, long term, input | Expression, constant consultations, negotiation, output |

| Participants | General population, public debate | Specific stakeholders, administrators, technocrats, expert debate | |

| Choice | Established preferences of population | Adaptation to changing external circumstances | |

| Justifiability | Sources of knowledge | Tried and tested traditions rooted in a community | General applicable universal doctrine |

| Changes | Protection of established rights against threats, fear for future | Innovation and expansion, solving problems from the past, hope for the future | |

| Communal interests | Whole population, (re-)distribution, general welfare | Successful stakeholders, indirect trickle-down to population |

The territorial perspective favours stable territories with distinct and hierarchically coordinated competencies. These are the basis of a legitimate institutional framework. Not only sovereign national states, but also regional and local administrations, should have their distinct responsibilities and autonomy. Neoliberalism challenged this.

In contrast, the relational perspective regards this kind of territorial parochialism and fixed hierarchical competences as illegitimate. Their legitimate institutional framework revolves around cooperation based on shared interests in multiple flexible networks.

Consent to these networks is organised through constant consultations and an expert debate between specific stakeholders, which help adapt policies to changing external circumstances. This kind of flexible coordination between stakeholders is, however, illegitimate from the viewpoint of the territorial perspective.

Instead, established spaces with fixed forms of consent are valued from the territorial perspective. Through these, the population can express their established preferences. The general population's involvement through elections is crucial for them.

The territorial perspective thus looks backwards and inwards, while the relational perspective looks more forward and outward. This is linked to the different ways in which each perspective justifies policies.

From the relational perspective’s viewpoint, policies are justified through general applicable knowledge. Universal knowledge concerning matters such as global warming or global competition can be used to solve the problems of the past, and create a better future.

Meanwhile, the sources of knowledge the territorial perspective uses to justify policies are predominantly based on tried and tested traditions. They are rooted and accepted in a specific community. Besides this, the protection of established rights against new and external threats justifies policies from the territorial perspective. Distributing welfare within a territory serves communal interests.

In contrast, the relational perspective focuses more on the success of individual stakeholders trickling down to the population. This legitimises the initial growth in inequality under neoliberalism. However, the still-growing gap in wealth now delegitimises neoliberalism.

The differences between the two perspectives are a theoretical construction which helps us understand debates on the legitimacy of particular policies. Both perspectives are used to different degrees, and with varying success, in political debates.

Traditionally, cities have legitimised their policies more from the relational perspective, while in the countryside, the territorial perspective dominates. These differences are now becoming polarised by challenges to neoliberal urban-centred policies. The strong support for populist parties outside the big cities is a noteworthy illustration.

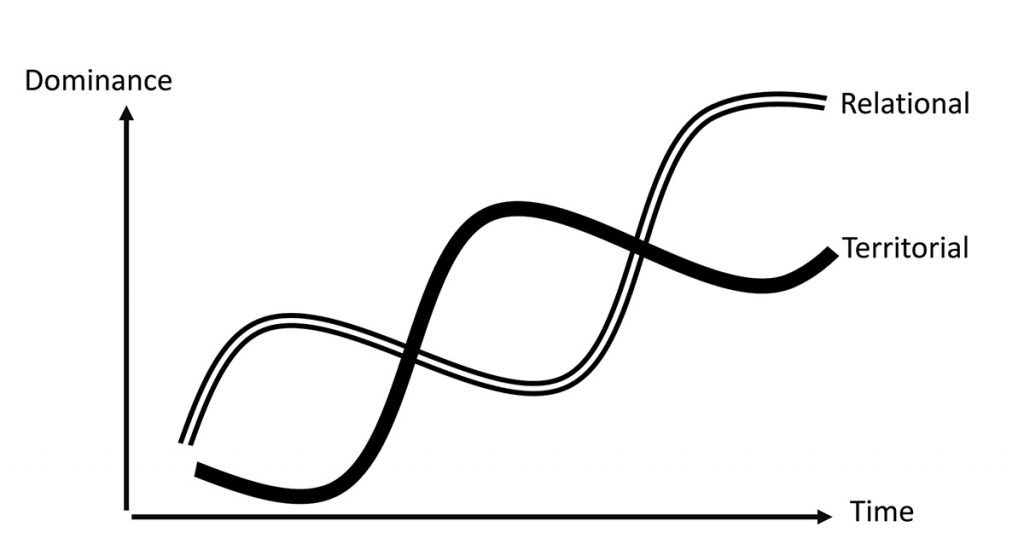

The dominance of a specific perspective varies in space and over time. Until the late 1970s, the territorial perspective was dominant. In Europe, welfare states were legitimised by their successful regulation and the homogenisation of their territories and population.

The current crisis of neoliberalism indicates yet another shift in dominance between the relational and territorial perspectives

This was, to a lesser extent, the case in the USA, where the territorial perspective was less dominant. The economic decline and shift of industrial production to Asia delegitimised state interventions. Instead, neoliberal policies rooted in the relational perspective legitimised competitive companies located primarily in globally connected big cities. Thus, the current crisis of neoliberalism indicates yet another shift in dominance between relational and territorial perspectives.

The figure below illustrates this alternating dominance between perspectives on legitimacy. It shows the gradual and relative alternation of the dominance of and co-evolution between both perspectives. It is a cycle not of absolute but of relative dominance.

For instance, the rise of neoliberalism did not result in the demise of territorial states. Even the most ardent supporters of neoliberalism see a role, albeit limited, for the territorial state.

The current delegitimation of neoliberalism will therefore not result in the delegitimation and disappearance of global relations. It will simply usher in a new phase in the cycle.