Illiberal governments in Central and Eastern Europe are following a conscious strategy of hollowing out interest representation and stifling or co-opting civil society organisations. Rafael Labanino explains how the authoritarian playbook works – and how interest groups adapt or fight back

Perhaps no other region has become more characterised by democratic backsliding than Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). As the yearly democracy reports of several democracy watchdogs attest, de-democratisation has been the rule rather than the exception in post-communist countries over the past 15 years.

Democratic backsliding has had a profound effect on the independence of civil society organisations (CSOs) as well as on their ability to influence policymakers.

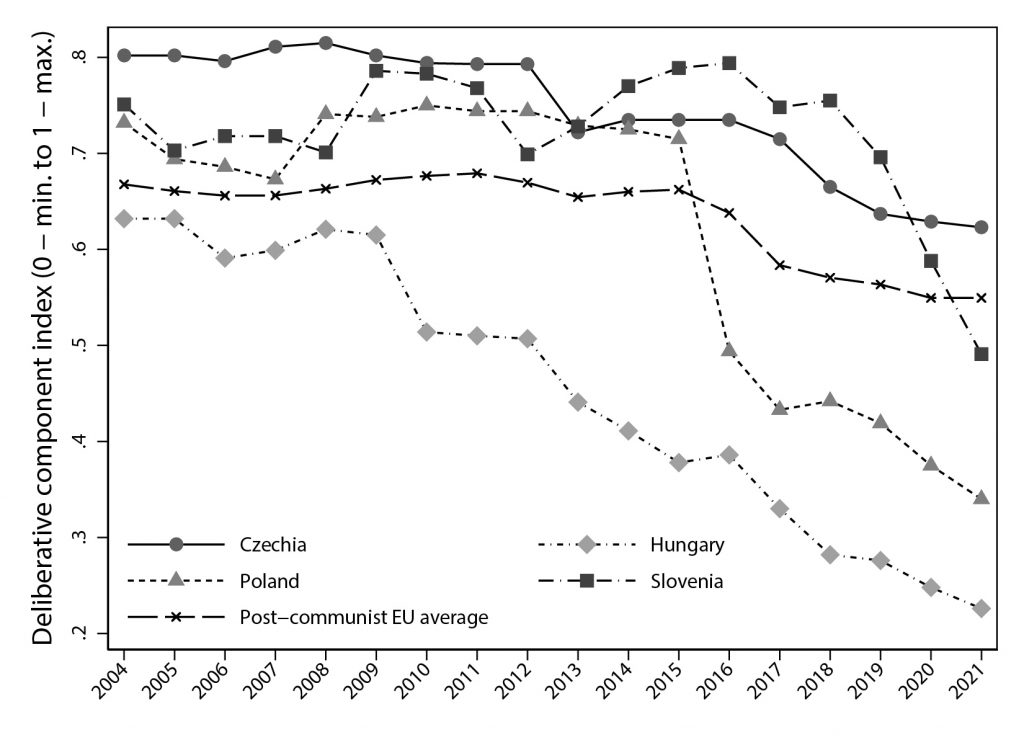

The most detailed index of democratic quality, the Varieties of Democracy or V-Dem project, provides a measure of how open policymaking is to societal interests, and the extent to which CSOs are allowed to operate freely.

Democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe continues to limit interest representation and reduce the policymaking influence of CSOs

The so-called deliberative democracy component index clearly shows the adverse effect of democratic backsliding. As the figure below shows, the tendency could not be clearer in Hungary with Viktor Orbán’s perpetual constitutional majorities since 2010, in Poland since the Law and Justice party took power in 2015, and in Slovenia under Janez Janša’s premiership between 2020 and 2022. But even Czechia saw a drop in its openness towards interest representation under the self-declared technocratic and managerial Babiš government between 2017 and 2021.

The articles in the latest Special Issue of Politics and Governance that I co-edited with Michael Dobbins examine the effect of de-democratisation on interest groups and interest representation in six CEE countries: Czechia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, and Slovenia.

Illiberal governments employ a three-pronged strategy against CSOs and interest group representation. First, under an illiberal incumbent it becomes more costly for CSOs to function because of an increased administrative burden. At the same time, financial resources are restricted: funds in general and funds for services.

Second, mechanisms and institutions for formal interest mediation are hollowed out or abolished outright. A lack of transparency in policymaking means not just restricted access to decision makers. Public discourse on policy can also become near-impossible.

Finally, as earlier studies show, illiberal governments actively nurture an 'uncivil society' of allied CSOs that share their policy goals and authoritarian worldview while demonising independent CSOs. However, the relationship is reciprocal. It might, in fact, be powerful vested interests that drive backsliding – as the struggles around anti-corruption legislation in Ukraine attest.

The authoritarian playbook restricts and demonises all independent CSOs, allowing illiberal governments to nurture an uncivil society that features only CSOs which share their worldview

Two possible counterstrategies to being excluded from policymaking are ‘exit’ or a ‘social movement mobilisation’ (SMOisation).

‘Exit’ is not necessarily dissolution. It can also constitute a withdrawal from public policy and a radical reduction of the organisation. At the other end, SMOisation means re-engaging with the public around a focus on community-building and mobilisation (protest).

Faced with exclusion from policymaking, CSOs must either withdraw from public policy or ally themselves with the illiberal government. Alternatively, they can mobilise as a form of protest

Groups under pressure might not give up advocacy, however. A focus on professionalisation; that is, internal development (staff, fundraising, lobbying, etc) might enhance their chances. They can choose to shift their lobbying/policy activities to the EU or the regional levels, away from hostile national institutions. Increased effort on networking with other CSOs, both at domestic and international/EU level, can also help even the odds.

And of course, allying themselves with the illiberal government – ‘Gongoisation’ – is also an option. Many of these organisations are not ‘illiberal’ in their ideology or goals, at least originally. For example, in Hungary, some conservative women’s and family organisations found the government’s family policy appealing. They openly promote government policy and in exchange have secured access to policymakers, along with generous funding.

Most of these strategies – except for ‘Gongoisation’ – are not mutually exclusive. Protest and community-building might serve as a vehicle for networking with other organisations – and, consequently, for influencing key policies. EU-level lobbying and cooperation might be an important tool in gaining leverage at the national level.

The available strategies are largely dependent on the context. Authoritarian actors often employ sector-specific strategies. They also try to divide and pacify the organisations. CSOs in sectors which are ideologically more homogenous can acknowledge illiberal threats earlier and launch joint action with greater ease than can more heterogenous CSOs.

Professionalisation, or branching out to EU or regional lobby forums, might be available only to those organisations which had more resources in the first place. Countering powerful vested interests in a weak and corrupt institutional environment such as Ukraine might be contingent on the cooperation of Western pro-democracy donors and local CSOs.

CSOs' internal decision-making is generally more democratic in CEE than in Western Europe. That is, CSO leadership is responsive to members. This lends legitimacy and gives incentives to be independent from the state.

Indeed, CSOs proved essential in mobilising mass protests against illiberal governments in Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia. However, the potential of civil society mobilisation in countering democratic backsliding depends, ultimately, on the overall level of de-democratisation.

Democratic backsliding may stimulate the ‘coming of age’ of interest groups as more defiant, responsive and strategically diversified. It may also contribute to the social mobilisation strategies of NGOs excluded from decision-making structures.

However, at a certain point, de-democratisation will threaten the existence of even the most resilient organisations. Perpetual struggle can eventually prove futile in a hostile political environment, amid attacks by government-controlled media, and ever scarcer financial resources. This would truly be a tragic outcome in a region where, just three decades ago, CSOs played such an important role in the countries’ democratic transitions.

No.25 in a thread on the 'illiberal wave' 🌊 sweeping world politics