Populist radical right parties have been remarkably successful in recent decades, and strategies to contain them regularly fail. Can non-radical parties do anything to counter them? Fabian Habersack suggests mainstream parties could signal ‘responsiveness’ while remaining committed to their policy goals

Rallying patriotically around the flag may bring governments temporary goodwill during the current pandemic. Times of crisis, however, also reinforce existing tensions between 'established parties' and populists.

Policy decisions are increasingly dependent on outside expertise, which shifts the focus to the effectiveness of policy decisions rather than input legitimacy. Especially in the long run, populists could thus be the beneficiaries of the crisis.

This is because democratic legitimacy doesn't derive only from policy effectiveness. More importantly for populists, it gives a voice to ‘the people’. Populist radical right (PRR) parties conceive of politics as a moral struggle between corrupt elites and the virtuous people, united by a general will. Their ideology often reveals just who they believe these virtuous people are. Whenever questions of distributive justice arise, PRR parties appear as defenders of the deserving ‘native’ population against undeserving foreigners. This demand for all-encompassing protection of the native population and renationalisation of politics constitutes the nativist core of PRR parties.

democratic legitimacy doesn't derive only from policy effectiveness. More importantly for populists, it gives a voice to ‘the people’

Governing parties, limited by long-term policy commitments, lack the capacities to respond to such demands. What makes it even more difficult to respond to populists is their Manichean, black-and-white understanding of democracy, which pits the interests of the common people against a conspiring elite. Political opponents are therefore, by definition, illegitimate, self-serving actors. It's an understanding diametrically opposed to the principles of liberal democracy, and it further aggravates tensions between the ‘responsive’ populists and ‘responsible’ non-radical parties.

This brings to the fore the old question of how to deal with populists. Following Meguid, mainstream parties can choose to ignore rival parties to downplay issue salience. They can also take an adversarial stance or co-opt their opponents’ positions. However, there is no sure-fire strategy.

Empirically, parties react differently to populists, though their attempts often fail. Populists are difficult to ignore once entrenched in their party systems. Strategies to ostracise them and erect a cordon sanitaire often lead to their radicalisation, and can even benefit them electorally. Cooperating with populists in government makes it impossible to demonise them. Finally, policy accommodation risks repelling previous voters. Even ideologically proximate, conservative parties face severe policy trade-offs in employing such a strategy.

Strategies to ostracise populists and erect a cordon sanitaire often lead to their radicalisation, and can even benefit them electorally

Neither aligning oneself with opponents nor countering their policy claims seems viable. Have non-radical parties reached an impasse?

I propose a new framework to analyse parties’ behaviour towards their radical rivals. It emphasises that non-radical parties have the tools to signal responsiveness while remaining committed to their policy goals. For the competition with PRR parties and their nativist core, this means that non-radical parties, for instance, selectively adopt positions (and rhetoric) where it is less costly. They also transform their rivals’ ambivalent ideological claims into specific policy positions that may follow similar lines of thinking, yet are more easily reconciled with their own core beliefs.

Koedam similarly argues that parties will more readily adjust their positions on secondary dimensions, depending on whether their primary voter mobilisation focuses on socioeconomic or cultural cleavage.

Policy adjustments do not always mean a change of heart. Instead of adopting composite policy positions, parties cherry-pick the positions they parrot.

To investigate how non-radical party families react to PRR parties in their midst, Annika Werner and I examined election manifestos from Austria, Germany and Switzerland over recent decades.

Drawing on election manifestos split into quasi-sentences (MARPOR), we first developed and validated a dictionary tapping into nativist ideas — as the core concern of PRR parties — and second, operationalised the concept of party families’ ideological cores. We thus identified quasi-sentences that either belong or do not belong to those cores.

We find that PRR parties devote by far the highest shares of their manifestos to nativism; green and radical left parties far less. However, parties allocate statements expressing nativism to their manifestos’ core to varying degrees. Here, the centrality of the cultural dimension for voter mobilisation is a better predictor than parties’ left-right position.

populist radical right parties devote by far the highest shares of their manifestos to nativism. However, parties allocate statements expressing nativism to their manifestos’ core to varying degrees

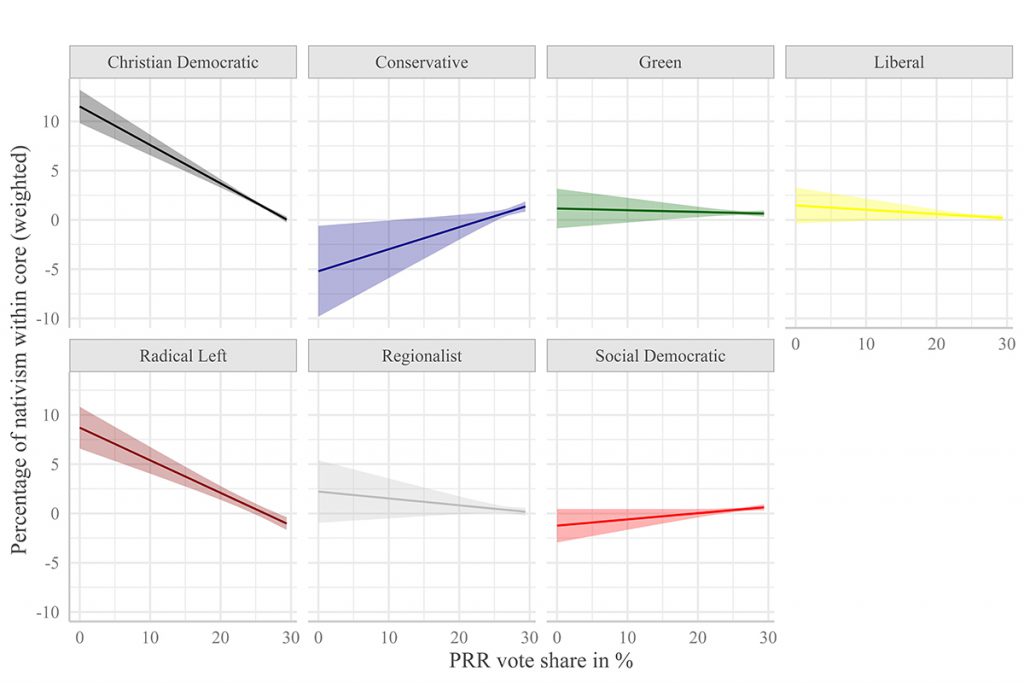

What explains this variation? In a final step, we analyse how parties respond to populist competition. This figure displays the effect of PRR success on the relative share of nativist claims within the core of party families’ manifestos (weighted by core sizes).

Populist radical right vote share and predicted share of nativism within party families’ core policy areas, 95% confidence intervals

We find that, on average, non-radical parties attribute significantly more nativism to less relevant policy categories for their constituency when responding to PRR competition.

The above figure in conjunction with the country-based regression results, however, also paint a more complex picture. For instance, in Germany and Switzerland, more populist success means less nativism in the Christian Democrats’ core, while in Austria we find the exact opposite.

Thus, with the important exceptions of Liberals in general, which do not react strongly to PRR parties, and of the Austrian Christian Democrats in particular, parties generally tend to target secondary areas to construct their nativist claims in response to populist competition.

Previous research suggests populist success triggers other parties to adopt similar composite positions on issues such as immigration. While I do not doubt the validity of these studies on the level of policy composites, I caution against over-interpretation, because these adoptions can hide important differences in how parties transform positions into specific policy claims more or less crucial for non-radical parties.

Other recent research shows that the distinction between hard and soft Euroscepticism, and the relationship between populism and more democracy, are highly complex, hiding important strategic choices.

Even when non-radical parties signal responsiveness towards their opponents, this does not necessarily show commitment to nativist ideas. Future research should conceive of programmatic adaptations as strategic choices rather than mere contagion effects.