Chih-yu Shih argues that we can meet Jean-Paul Gagnon’s democracy challenge across linguistic and cultural divides. He explores how 'critical translation' (aimed at 'relational' and not 'total texture') can yield results for those pursuing democratic commonality

How does Jean-Paul Gagnon’s proposal to build a ‘data mountain’ to understand democracy stand up to the challenge of translation?

Another linguistic system carries various different cultures. To translate democracy across linguistic divides, we must explore how strangers understand democracy through different cultural lenses. We must also explore what terms we might use to translate it for them. Ultimately, if pluriversal coexistence prevails, no single version of democracy can relate all.

For this reason, I would move away from Gagnon’s inductive approach aimed at achieving a 'total texture'. This assumes that the term democracy can be an anchor – or at least an independent complex. In practice, no such anchor exists.

To translate democracy across linguistic divides, we must explore how strangers understand democracy through different cultural lenses

All cosmologies make assumptions about relations between the human, nature, and the supernatural. We make such assumptions almost as a matter of course. This makes 'critical translation' essential to coexistence. A pluriversal deconstruction of democracy can entail a relational texture of democracy.

By 'critical translation', I mean the translation of the meaning of a term in one language into a different language. The translation is so abstract that we can pick up certain prototypical messages at the other end which attain meanings in the latter’s linguistic logic. We then re-translate these messages back into the first system. Its subscribers can thus appreciate how different their familiar concepts, values, or logics feel, once rid of their relational contexts. Let us conduct the exercise in relation to Chinese vs western conceptions of democracy.

The contemporary term for democracy in Chinese is 民主: people are the master / owner / host of themselves. There is no immediate parallel in Confucianism to the rights of nature, equality at birth, and the social contract. Given this, the first usages in 左 傳 (roughly 200–400 BC) of 民主 consistently referred to princes. The idea was that princes were 'the people’s master,' as opposed to the people being their own master.

The contemporary term for democracy in Chinese is 民主: people are the master / owner / host of themselves

According to Confucianism, the people’s welfare is the core of princely function. But why should 'the people’s master' be concerned about the people’s welfare, without a social contract? This question makes one suspect the authoritarian Chinese Communist Party embraces no such concern.

Yet, the reasons actually lie in the classic texts. One popular elaboration, which inspires the Chinese Communist Party’s interpretation of democracy, is that the prince’s legitimacy lies in the Mandate of Heaven, and that Heaven sees and hears what the people see and hear.

A useful metaphor is the natural or heavenly contract, which analogises an agreement between the prince and Heaven. The notion of heaven is reified through the people’s perceptions of the prince. Such reification creates a cosmological order that subjugates the prince to the people. Here, the distinction between the 'people’s master' and the 'people being the master' becomes blurred.

The social contract obliges the people to look after their own interests by limiting the power of the government. The natural contract obliges the prince to look after the people’s interests by predicting that Heaven will remove his Mandate from the exploitative prince. In the latter case, the people's agency is not informed by their rights to limit the power of the prince. Rather, it is informed by their ability to migrate, spontaneously, elsewhere.

As a result, liberal democrats are shocked by the Chinese people’s lack of agency to control the power of their government. The Chinese Communist Party is likewise shocked by liberal politicians’ lukewarm attitude toward the welfare of the entire population, and its future generations.

At the abstract level, Confucian cosmology reveals how and why the prince and his people were related in a far more complicated system than simply one of top-down control, lumped together indistinguishably in authoritarianism with other non-Christian, postcolonial, or de-national communities.

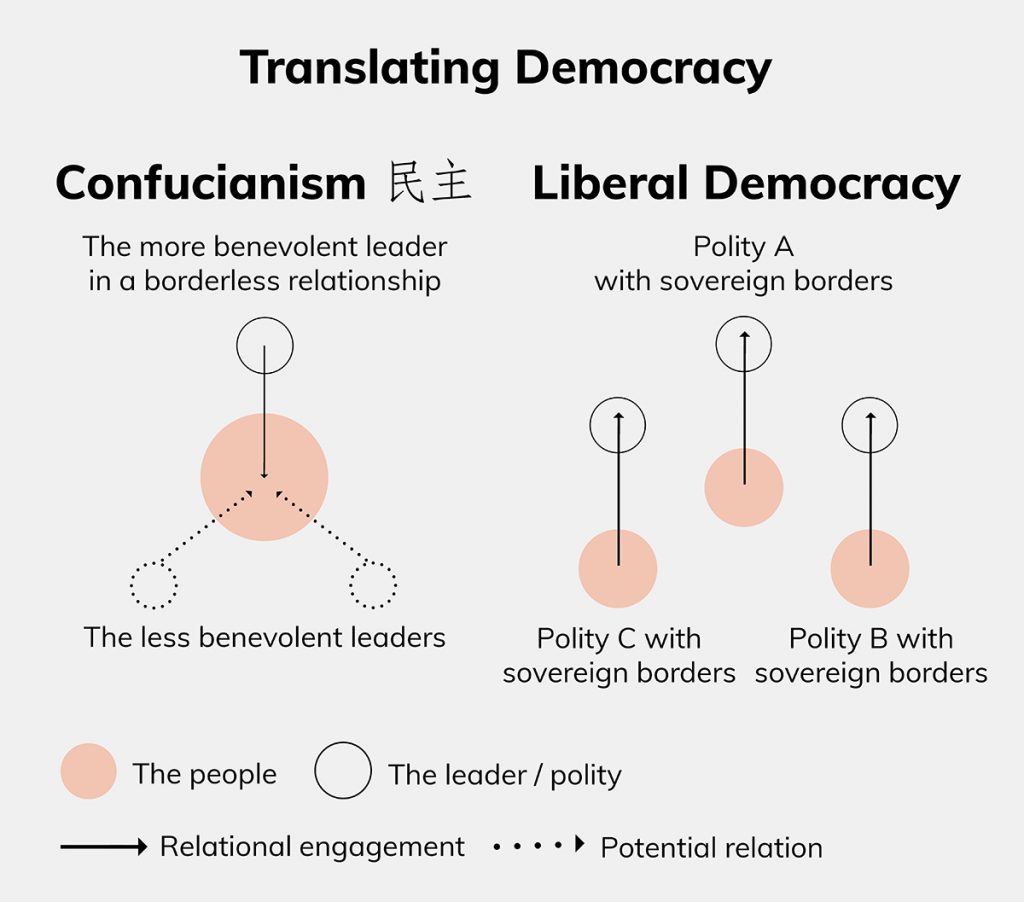

A 'critical translation' of liberal democracy and Confucianism 民主, by revealing their contrasting relational preparations, effectively embodies an epistemological tour in each other’s cosmologies:

Consider defining liberal democracy as exercising natural rights to the government by consent. And consider defining Confucianism 民主 as spontaneously following the most benevolent leadership.

To introduce liberal democracy to Confucians, therefore, we must enlist God to highlight the rights and laws of nature. God informs the Christian cosmology that survived the 100-year religious war. This war has, since then, divided the world into sovereign domains. The consensual rights of nature constitute the guiding principle of relations between citizens and authorities. This principle ensures that dictators do not control the government. Institutionally, bottom-up participation enables the people to control the government.

In a borderless world, there is no fixed sovereignty to prevent the people shifting their loyalty to someone more benevolent

To introduce Confucianism 民主 to liberal democrats, we must enlist the Mandate of Heaven, which expounds empowering the people to abandon non-benevolent leaders. The heavenly mandate suggests a borderless world. In such a world, there is no fixed sovereignty to prevent the people shifting their loyalty to someone more benevolent. The heavenly relation ensures dictators do not control the people. Institutionally, the top-down mass line approach (or benevolence) dissuades the people from exiting. Note, though, the challenge of contemporary sovereign order to the plausibility of 民主.

Together, liberal democracy and Confucianism 民主 point to a common desire for a style of policymaking exempt from a monopoly. This despite the fact that, in a practical sense, such an ostensibly universal definition of democracy reflects pluriversal relationalities, and alludes to different values.

This article is the eighteenth in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series