Youth wings of political parties are a key part of the pipeline to power. However, among their members, fewer women than men would consider running for public office. According to Sofia Ammassari, if we want to redress women’s underrepresentation in parliaments, youth wings are a good place to start

More women than ever are being elected as MPs. Yet in most of the world's parliaments, women remain underrepresented. Some explanations for this inequality concern how institutions such as parties and parliaments are organised and function. With their formal and informal rules, norms and practices, these institutions reinforce the idea that politics is a man’s world.

Other explanations for women's underrepresentation refer to the ways in which women have been socialised. Well-established norms associate women with the private sphere and men with the public one. Women, therefore, tend to display less political ambition than men. They have less desire to run for public office, and even when their parties do ask them to run, they are more likely to say ‘no’.

Women have less desire to run for public office, and even when their parties do ask them to run, they are more likely to say ‘no’

In the European Journal of Political Research, Duncan McDonnell, Marco Valbruzzi and I published a study based on our survey of political parties’ youth wing members. We aimed to discover whether the gender gap in political ambition was already present among this distinct group of politically engaged young women and men. What we know from previous research on youth wings is that many members aspire to run for office. What we don’t know is whether women are already less ambitious than men at this early stage of the pipeline to power, or whether they become so later.

We surveyed youth wing members from six centre-Left and centre-Right parties in Australia, Italy, and Spain. Our findings reveal a worrying trend. Not only do women represent only a small minority of youth wing members; they are also much less likely than men to say they would consider standing as a candidate in the future. If parties are genuinely interested in improving women’s representation and influence, they should look more closely at their youth wings.

Party youth wings are where many of tomorrow’s leaders are formed. Think of current Prime Ministers on the Left and Right in major democracies: Giorgia Meloni (Italy), Olaf Scholz (Germany), Ulf Kristersson (Sweden), Anthony Albanese (Australia). All started their careers in party youth wings. And, in most cases, so did their main opposition leaders.

Beyond prime ministers and party leaders, research into the careers of parliamentarians shows how sizeable proportions of MPs have held senior positions in youth wings. To understand the causes of women’s underrepresentation in parliaments and cabinets, therefore, analysing these party sub-organisations would be a useful starting point.

That is precisely what we did in our study. We surveyed over 2,000 members of three youth wings on the centre-Left (Young Labor in Australia, Young Democrats in Italy, and Socialist Youth in Spain) and on the centre-Right (Young Liberals in Australia, Forza Italia Youth in Italy, and New Generations in Spain). Among other questions, we asked members whether they would like to stand as candidates for their party one day.

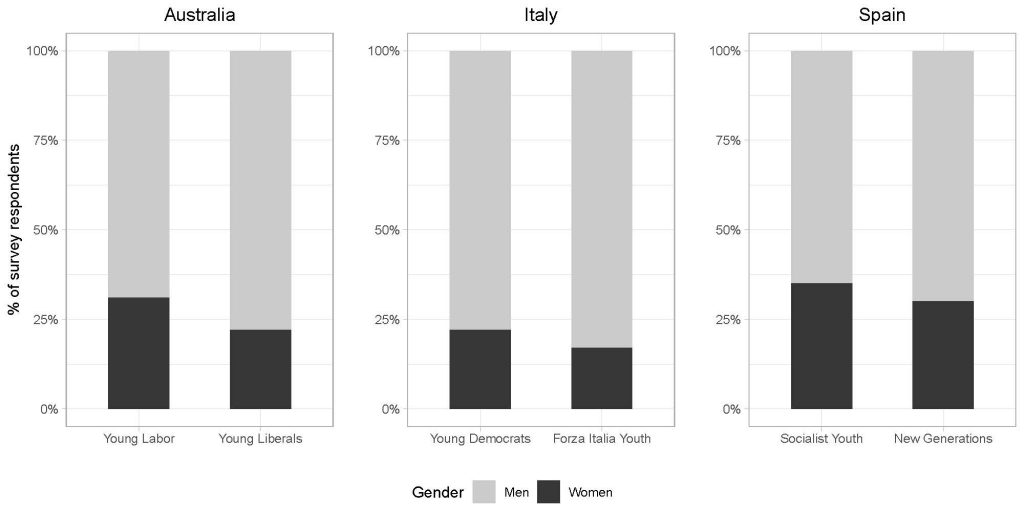

The first key finding of our research is that, just like their senior parties, youth wings are men-dominated. Overall, women made up about a quarter of our respondents. As the graph below shows, there are no big differences across the six youth wings. In fact, women respondents account for less than one third of members in five youth wings. The only exception is Spain's Socialist Youth. Among the three countries, Italy has the greatest gender imbalance.

In terms of absolute numbers, youth wings are boys' clubs

Notably, we can see some variation by party ideology. In each country, the centre-Left youth wing has a higher proportion of women than the centre-Right one. Nonetheless, the picture emerging from our survey is that, in terms of absolute numbers, youth wings are boys’ clubs.

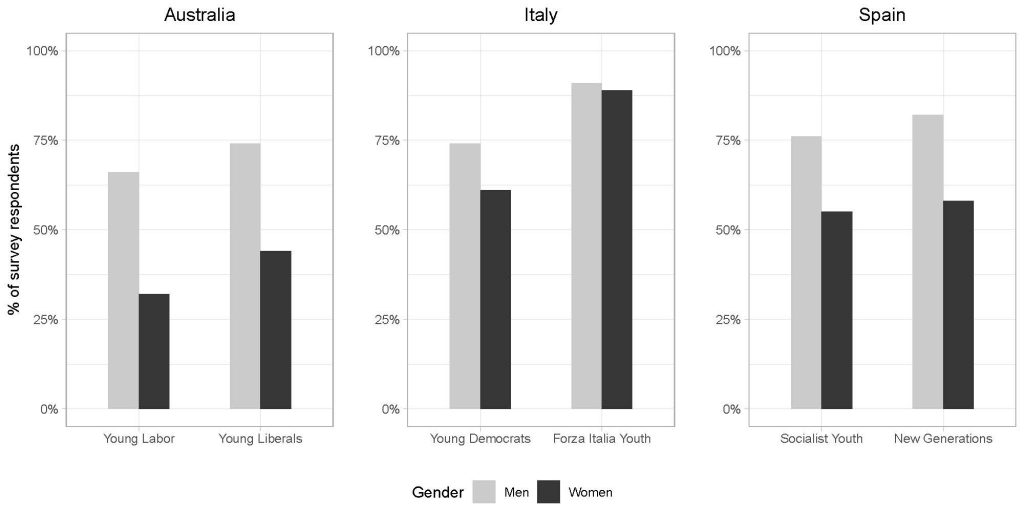

Our second key finding is that women youth-wing members are less interested than their men counterparts in running for office. Women who said they would like to stand as candidates in the future made up about 50% of our respondents. This compares with 75% of men who expressed an interest in standing.

The graph below displays the gender distribution of these respondents across the six youth wings. The largest gender disparities in ambition are in Australia, where we find gaps of at least 30 percentage points. And in both Australia and Italy, ambition gender gaps are greater in the centre-Left youth wing than in the centre-Right one.

Overall, the evidence is clear: even among this group of politically interested, skilful and engaged young people, women are less interested than men in pursuing a career in public office.

So, what can parties and youth wings do to make parliamentary careers more appealing to women? First, parties should begin to actively recruit higher numbers of women members. Doing so at the youth wing level, when patterns of inequality between women and men are not as established as when they grow older, should be a key priority.

Recruiting more women at the youth wing level, before patterns of inequality become entrenched, should be a key priority

Second, youth wings should ensure that women and men are provided with the same opportunities to be trained and recruited for office. This means combating practices such as homosocial mentoring – in which older men in the party (who, obviously, are the majority) only mentor young men – and adversarial party cultures which disadvantage women.

In other words, we need to fix the youth wings of today, to have more gender-equal parliaments tomorrow.