The IMF is not only a ‘lender of last resort’ but also a security actor. New data and analysis from Bernhard Reinsberg and Daniel Odin Shaw at the University of Glasgow show that IMF interventions often have a negative effect on human security

Most people think of the International Monetary Fund as an economic actor which exists to promote macroeconomic stability and prevent financial collapse by providing emergency loans. Its support comes with loan conditions which shape economic policy and state institutions. This can have a profound impact on security.

Theoretically, the impact of the IMF is ambiguous. On the one hand, IMF loans could stabilise countries by providing much-needed credit that can prevent state collapse and promote public goods provision. The IMF has also become increasingly involved in advising countries on institutional reform, digital government, and cyber-security.

On the other hand, the market-liberalising conditions included in IMF programmes could have pernicious side effects. Austerity could lead to labour unrest. Price hikes could increase inequality and civil strife. The removal of structural distortions could increase the risk of coups d’état as elites are threatened with losing long-held privileges.

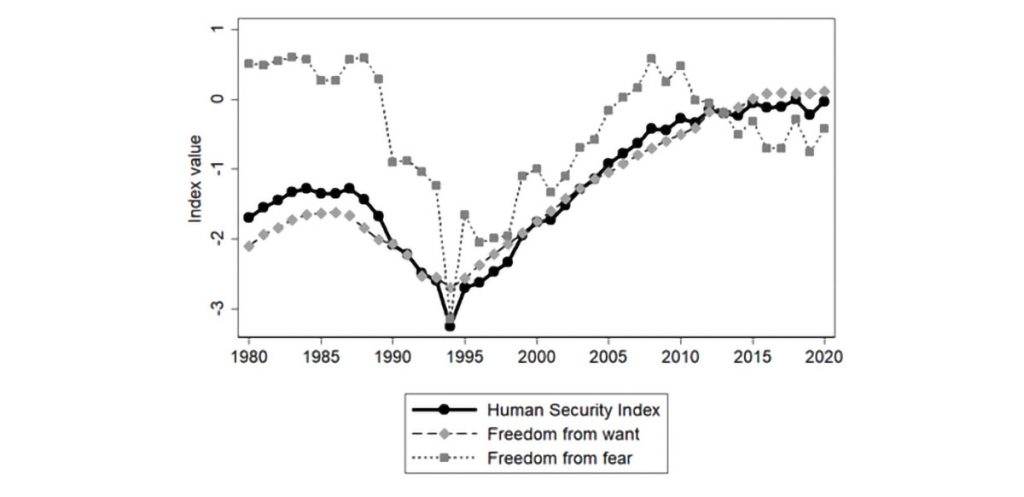

While the IMF can affect human security in multiple ways, systematic research on this topic has been hampered by a lack of reliable cross-country data on human security. Our new Human Security Index, which builds on a rich body of conceptual work, addresses this gap and helps readers learn more about human security across the world.

Human Security Index data is available for over 180 countries, from 1980 to 2020. It captures the two constitutive dimensions of human security: freedom from want and freedom from fear. Freedom from want is about individuals’ access to education, food, healthcare, and fresh water. Freedom from fear, meanwhile, measures the absence of homicides, civil war, terrorist attacks, and gender-based violence.

Our Human Security Index captures freedom from want and freedom from fear. It builds on a rich body of conceptual work, and its 11 indicators all measure the same underlying concept

Overall, we collected data on 11 indicators, discussed in the human security literature as the most relevant. We then used factor analysis to confirm that these indicators all measure the same underlying latent concept. To our knowledge, this makes the Human Security Index the only theoretically driven and empirically validated measure of human security.

The primary finding of our research is that IMF programmes have, on average, a pronounced negative effect on human security in the years that follow them. Some scholars may challenge our findings, countering that states seeking IMF support have weak institutions or face economic troubles which would manifest in low human security. They would claim that it is not IMF interventions per se causing insecurity, but long-term weak fundamentals causing IMF interventions and insecurity.

We address this challenge using an instrumental-variable analysis. This removes the confounding effect of country-specific factors such as weak fundamentals. Analysing the data through this lens, we continue to find that IMF interventions on human security have a negative effect.

The Rwandan case below is a good illustration of our findings. It shows how an intervention aimed at ensuring financial stability can have long-term negative impacts on human security. On 24 April 1991, Rwanda turned to the IMF for a Special Drawing Rights 30.66 million Structural Adjustment Facility. It then witnessed declines in human security, further propelled by the outbreak of a civil war in 1991 and the subsequent genocide in 1994.

In Rwanda, IMF-mandated measures, including austerity, privatisation of public utilities, and currency devaluation, contributed to public anger, ethnic tensions and state weakness, with tragic results

While some argue that the causes of these tragic events have deep historical roots in the era of European colonialism, others have pointed to the destabilising role of IMF programmes in the run-up to the conflict. Most notably, IMF-mandated measures, including austerity, privatisation of public utilities, and currency devaluation, contributed to public anger, ethnic tensions and state weakness.

Rwanda is a particularly clear and extreme example of IMF interventions contributing to poor human security outcomes. However, it does suggest several causal mechanisms which are broadly plausible and applicable to other cases.

Liberal ‘shock therapy’ measures that seek to bring macroeconomic stability can also spark social and political unrest, which contribute towards violence. Over the longer run, the hollowing-out of the state could also weaken recipient countries, socially and economically. This also contributes to reduced security outcomes.

Such outcomes are not only bad for human security but also run counter to the IMF’s own goals. Countries suffering from underdevelopment and civil conflict will struggle to pay their debts and engage fruitfully with the global economy.

While our research shows an overall negative effect of IMF adjustment programmes on human security, it would be an oversimplification to suggest that such interventions are entirely negative. Clearly, macroeconomic stability is a necessary component of long-term political and social stability.

Liberal ‘shock therapy’ measures and the long-term hollowing-out of the state weaken recipient countries in ways that not only jeopardise human security but also run counter to the IMF's own goals

However, the potential for dangerous side effects that undermine human security means that more attention should be paid to context when designing adjustment programmes and other international interventions. Measures that work in one context may be dangerously destabilising in another.

More research is needed, therefore, on how and when IMF interventions can succeed without damaging human security. Meanwhile, international organisations such as the IMF should make the protection of human security a primary concern, even when implementing primarily economic interventions.