Stefano Braghiroli and Andrey Makarychev chart the Estonian National Conservative Party (EKRE)'s recent appeal, for the first time, to Russian-speaking minorities – a similar experiment to the Lega transformation into a national party in Italy. Unlike the Lega, however, EKRE faces the obstacle of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

At Estonia’s last local elections in October 2021, the ethno-exclusivist Estonian National Conservative Party (EKRE) actively appealed, for the first time, to Estonia’s significant Russian-speaking minority. It even presented Russophone candidates in its list.

EKRE has frequently alienated Russian-speaking Estonians, as part of its traditional ethnocentric, illiberal outlook

This from a party which, since its entry into Estonian party politics in 2021, has been ideologically hostile to cosmopolitanism, multiculturalism and supranationalism. EKRE has always embraced an ethnocentric, illiberal, socially conservative, and relatively anti-modernist agenda. It presents itself as the only alternative to the political mainstream.

EKRE has also opposed a more inclusive approach towards national minorities. Notably, it antagonised Estonia’s significant Russophone community, embracing slogans such as ‘Estonia for Estonians’, with an intransigent position towards Russia.

What, then, caused this change of heart?

EKRE’s 2021 electoral campaign in predominantly Russophone parts of Estonia represented an experiment. It was an attempt to extend the Estonian conservative agenda beyond the party’s traditional ethno-centric comfort zone into segments of the electoral market notorious for their political alienation.

EKRE participated in the trilateral coalition government led by Jüri Ratas in 2019–2020. This was a major boost to its political identity as a non-exclusionary and inter-communal party. Thus, EKRE faced a challenge: inscribing its conservative nationalism into the specific context of the Russian-speaking electorate, away from ethno-centrism.

EKRE's campaign strategy incorporated traditional far-right politics of fear in three ways, appealing to conservative-leaning voters regardless of their ethnicity. First, the party identified family values as a cornerstone of its social conservative agenda, grounded in hegemonic masculinity and anti-multiculturalism.

Second, EKRE was critical of the EU-led Green Deal and 'just transition' because of its detrimental effects on the oil shale industry. This sector is one of the major employers in the Russophone county of Ida-Virumaa.

Third, the party took a critical stance (so-called 'medical populism') towards the government's restrictive anti-pandemic measures. It was an attitude expected to find support with Ida-Virumaa residents, among whom vaccine scepticism runs high.

During its campaign in minority-populated areas, the Estonian Language Inspectorate reprimanded the party for prioritising Russian over the native tongue. EKRE appropriated Soviet-Russian cultural references to increase its appeal among locals. On Estonian independence day, for example, the party organised a concert of Soviet-era popular music. It even campaigned in the city of Narva with the Trumpian slogan: 'Make Narva Great Again!'

The Estonian Language Inspectorate reprimanded EKRE for prioritising Russian during its campaigns. The party also whitewashed Russian-speaking activists' views about Putin's regime

Meanwhile, the party recruited local Russian-speaking activists, repeatedly whitewashing their views on the experience of Soviet occupation, World War II, and Putin’s regime.

EKRE's campaign strategy is not unique in the history of conservative populism. Indeed, one can trace parallels in the transformation of the Italian Northern League after 2018.

The Northern League / Lega Nord was established as an autonomist independence movement around the idea of Padania in the North of Italy. The party was hostile to central government and the South of Italy (Mezzogiorno), which it depicted as parasitic and freeloading. However, under the leadership of Matteo Salvini, the party undertook an ideological and strategic restyling, giving it appeal among Southern voters.

Delegitimised by multiple scandals but with a desire to expand nationwide, the Lega Nord co-opted local operatives in Southern Italy. The party managed to profit from the traditional clientelist networks that characterised the Mezzogiorno.

On the eve of the 2018 parliamentary elections, the party removed from its name all reference to its Northern identity, becoming simply the League (Lega). Progressively, Salvini shifted the party’s compass decisively towards the radical right and archived the ideological paraphernalia of Padanian secessionism.

Along with the party's ideological restyling and change in narrative, a number of non-ideological performative acts accompanied the electoral conquest of the South. Salvini wore slogan T-shirts and hoodies simpatico with the South, ate Neapolitan pizza, and sang traditional Southern songs.

Encouraged by a consistent rise in popularity during that period, the Lega, in a relatively short period of time, transformed itself into the national party it remains today.

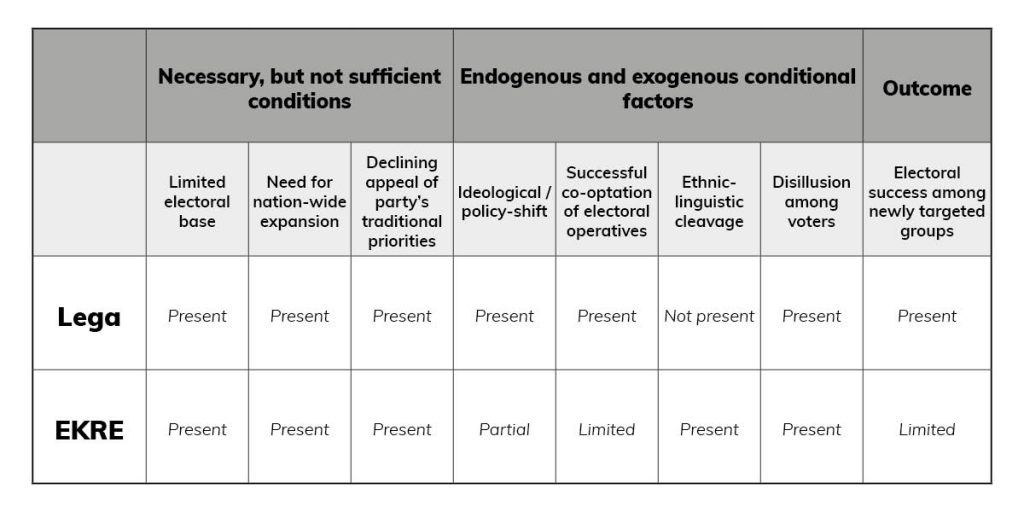

EKRE's trajectory shares similarities with the one mapped out earlier by the Lega Nord. It is, in essence, conservative populists redefining former foes as friends to expand their appeal and transform their party.

The Lega and EKRE redefined former foes as friends to expand their appeal and transform their party

EKRE’s shift highlights the growing emphasis on cross-communal issues and the slow (but constant) attempt to downplay ethnically exclusionary issues such as memory politics. The party has also tried to create separate (but increasingly overlapping) electoral constituencies. This is not too different from Salvini’s sponsored initial electoral lists in the South of Italy.

Yet in contrast with the Lega, EKRE’s turn to the East would, if it were a film, still be in production. EKRE support among Russian speakers in the local elections was merely moderate. The party gained only four seats in two of Ida-Virumaa's eight districts.

More importantly, we must question how far EKRE's new strategy will appeal in the changed international context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since the invasion, the party has taken a tough anti-Russian stance, undermining its new approach to the Russophone electorate. EKRE even proposed to demolish all Soviet-era monuments in the country, a move unpopular with Russian-speaking Estonians. Most notably, the party's stance has led to the de facto disaggregation of the EKRE branch in Narva municipality. Production on this particular film, it seems, is now on pause.

Stefano and Andrey are authors of the recent East European Politics article Conservative populism in Italy and Estonia: playing the multicultural card and engaging 'domestic others'

[…] https://theloop.ecpr.eu/comparing-ekres-strategy-towards-russophone-estonians-with-italys-lega/ dostęp: 10.02.2023. […]