Bulgaria has just held its fifth national election in two years. As in the previous four, there was no clear winner. The small lead for Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria (GERB-SDS) resolves nothing. Indeed, argues Ildiko Otova, it probably renders political stability even more difficult to secure

Citizens for the Development of Bulgaria, GERB, came on to the scene as an anti-elitist party. During the long years of its administration, the party has normalised populism, even forming coalitions with extreme-right parties. In this de-ideologised environment, effective policy-making on behalf of citizens is impossible.

By 2020, years ineffective administration and corruption had triggered protests. Activists demanded the immediate resignation of government ministers. But Bulgarian citizens' most vehement defender turned out to be President Rumen Radev. Disengaging himself from his constitutional powers, and raising a fist, Radev usurped the justified civil protest.

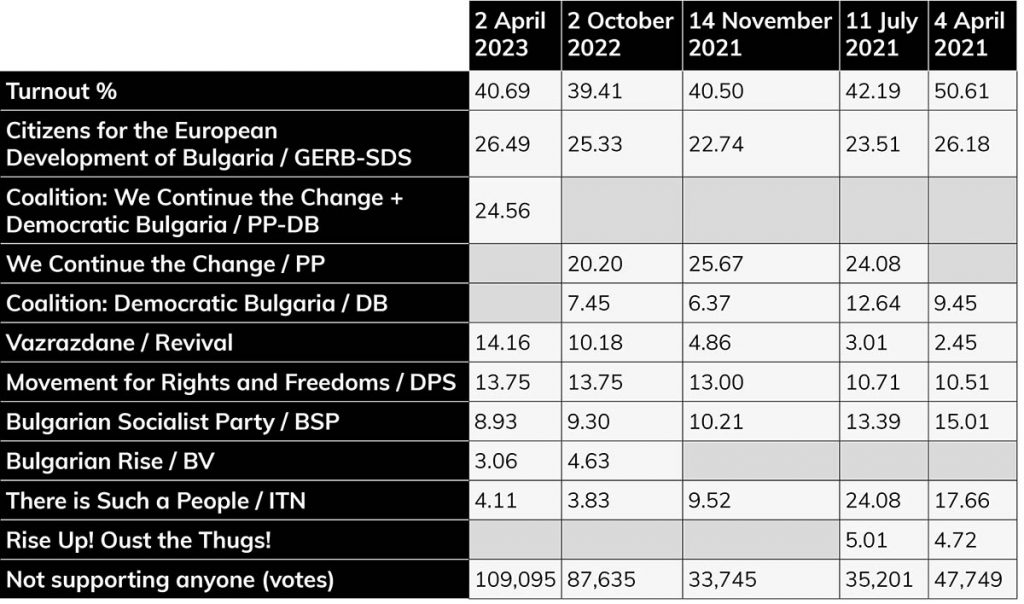

The GERB administration formally held out until the regular elections. During the next two years, however, Bulgaria's crisis intensified. One regular election and a series of snap elections have failed to produce a stable administration.

A brief coalition government of PP, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), There Is Such People (ITN) and the DB, was in power for the first half of 2022. Since then, caretaker governments led by President Radev have been in charge. Radev has been pounding his fist on the table in an anti-democratic way – but in keeping with Russian interests.

Most recently, he has refused to participate in joint European supplies of weapons for Ukraine. He intimidates journalists, and clings to a revisionist version of history, which implicates him in antisemitism.

The 2020 protests created numerous pop-up political projects. These offered anti-elitism and technocrat populism (PP) or hybrid forms of anti-establishment and nativist tendencies (ITN, Bulgarian Rise). All this gave impetus to the ultra-nationalist, anti-establishment party Vazrazhdane.

Throughout five consecutive electoral campaigns, debate in terms of exchange of ideas and policy proposals has been virtually non-existent. The most recent election was particularly devoid of real proposals.

Throughout five Bulgarian electoral campaigns, debate in terms of exchange of ideas and policy proposals has been virtually non-existent

The antagonism between the main opponents PP-DB and GERB boils down to change versus stability or 'goodies versus baddies'.

This absence of ideas, combined with ideological destitution, is particularly noticeable in the BSP. This party launched an offensive against 'gender ideology', basing its entire campaign on that premise.

New faces with no new ideas, old faces with ideological schizophrenia, corrupt faces disguised behind Euro-Atlantic values.... Sadly, this is all that Bulgaria's bland political show has to offer. Unsurprisingly, it has generated meagre interest among Bulgarians.

Nevertheless, some formations are working actively and successfully. Support for Vazrazhdane increased, with a jump in numbers to over 100,000 votes at the last election. A party of this type has never before wielded such influence on Bulgaria's political scene.

The referendum against Eurozone membership is among the reasons for the party's success. Vazrazhdane has successfully enforced its own agenda by pitting 'national sovereignty' against 'agents of foreign interests'. Moreover, it refuses emphatically to cooperate with other parties, retaining its anti-establishment character.

Vazrazhdane has successfully pitted 'national sovereignty' against 'agents of foreign interests'

Party leader Kostadin Kostadinov's active fieldwork is not to be underestimated. He has been out visiting small settlements where other politicians rarely or never go. He has also focused his campaign efforts on Bulgarian emigrants abroad. Kostadinov's vivid presence on social networks is reinforced by the sizeable share of media time at his disposal.

ITN was also brought back to life in the National Assembly, after dropping out at the previous elections. The favourite populist instrument, the referendum – in that case, for a presidential republic – has refocused attention on the formation led by showman Slavi Trifonov. Strong opposition to the short-lived status-quo of PP meant that disaffected citizens continued to regard it as an anti-establishment actor.

Both Vazrazhdane and ITN gain from the anti-establishment vote, which was the great de facto winner of the recent elections.

A considerable sector of Bulgarian society wants to see a change of elite, and some sort of new social contract. However, five consecutive elections have failed to produce this change through a democratic mechanism. Anger, despair and resentment have all accumulated amid a difficult socioeconomic situation, and rising inflation.

Abstention rates, meanwhile, remain high. Nearly 60% of voters did not bother to go to the ballot box. Moreover, a record 109,095 Bulgarians who did make the trip to the polling station chose only to tick the box marked 'Not Supporting Anyone'.

Right now, the situation seems irresolvable. Parity between the two foremost political forces and the forthcoming local elections have put most of the players in a tricky situation, unlikely to result in the formation of a government. A sixth election looks just around the corner.

Without some serious work on developing proposals of real political substance, Bulgaria will simply endure more anti-establishment politics

The real competition should (but probably won't) be for those voters who currently do not vote or do not support anyone. We shouldn't underestimate the idea that only Vazrazhdane is a real contender for their vote.

Long-distance runner Kostadinov is undoubtedly in the reckoning for the next European elections. The other political players will be targeting the next snap national elections, or the local elections.

The current situation calls for serious work on developing proposals of real political substance. Otherwise, Bulgaria will simply endure more anti-establishment politics. The two years spent under the power of populist, anti-establishment forces devoid of ideology, and working purely in the interests of Radev, offer stark warning of the dangers of the anti-establishment trend.