The UK may be in the limelight at COP26, with the government having set highly ambitious targets for net zero by 2050. But, Tim Bale argues, evidence suggests that parts of the British electorate – largely Tory supporters – may be sceptical about the merits of the policy

In the run-up to the COP26 summit in Glasgow, a group called CAR26 persuaded the Daily Telegraph – one of the UK’s best-selling, Conservative-supporting newspapers – to run a story on a recent poll it had commissioned. The poll revealed that four out of ten adults ‘support a national referendum to decide whether or not the UK pursues a Net Zero Carbon policy.’

This may, of course, turn out to be, as many suspect, an ‘astroturf’ campaign – one set up to look like a grassroots effort but in reality funded by special interests. But it is a reminder that there remains a significant portion of the Tory milieu who don’t accept climate change as real; or at least who don’t believe there’s much point in the UK trying to do much about it when big carbon emitters like China, Russia, India, Australia and Saudi Arabia don’t seem to want to bother.

there remains a significant portion of the Tory milieu who don’t accept climate change as real; or at least who don’t believe there’s much point in the UK trying to do much about it

Interestingly – indeed some would say rather bizarrely – CAR26 doesn’t seem to have asked (or at least permitted the publication of the responses to) the obvious next question, namely ‘If such a referendum were held, which way would you vote?’ Presumably, this was because the answers might not have made for quite such headline-grabbing reading for climate-change sceptics: at least some of the 42% of respondents who said they either tended to support or strongly supported a referendum on net zero would end up voting for rather than against the policy.

Liberal Democrat supporters, for example, are normally pretty keen on measures to tackle global warming. The fact that some 46% of them said they supported a net zero referendum (as opposed to 45% who did not) suggests that by no means all Brits backing a vote do so because they think climate change is nonsense or something no-one can do much about.

Still, it is noticeable that net support for a referendum is strongest among Conservative Party supporters (46 vs 33% opposed) but much weaker (39 vs 35%) among Labour supporters. It is also noticeable that those who voted to leave the EU in 2016 are considerably more supportive (47 vs 28%) than those who voted Remain (41 vs 39%).

there is good reason to think that some differences between the reactions to the idea of a net zero referendum among the supporters of different parties reflect differences in underlying values

To some extent, this will be tied up with the demographics of both Tory and Leave (pro-Brexit) voting – something that becomes obvious when you look at support for a net zero referendum among different age groups. There is a big contrast, for instance, between the enthusiasm shown for such a vote among those 65 and older (who support a referendum by a 47–35 margin) and the relative lack of enthusiasm (the margin is 35–27, with 37% saying don’t know) among those aged 18–24.

It’s also possible, of course, that those who have been on the winning side in a referendum tend to think they’re a good thing, and vice versa. We know, too, that people’s support for referendums also tends to vary with how likely they think their opinion will be shared by the majority.

Notwithstanding all those caveats, however, there is good reason to think that some of the differences between the reactions to the idea of a net zero referendum among the supporters of different parties reflect differences in underlying values – values which are often linked to their partisan preferences.

Those values can be summed up in all sorts of ways, but one of the most enduring is to differentiate between materialists and postmaterialists. The former prioritise (among other things) economic growth and security; the latter put more emphasis (again among other things) on the environment and solidarity with the developing world.

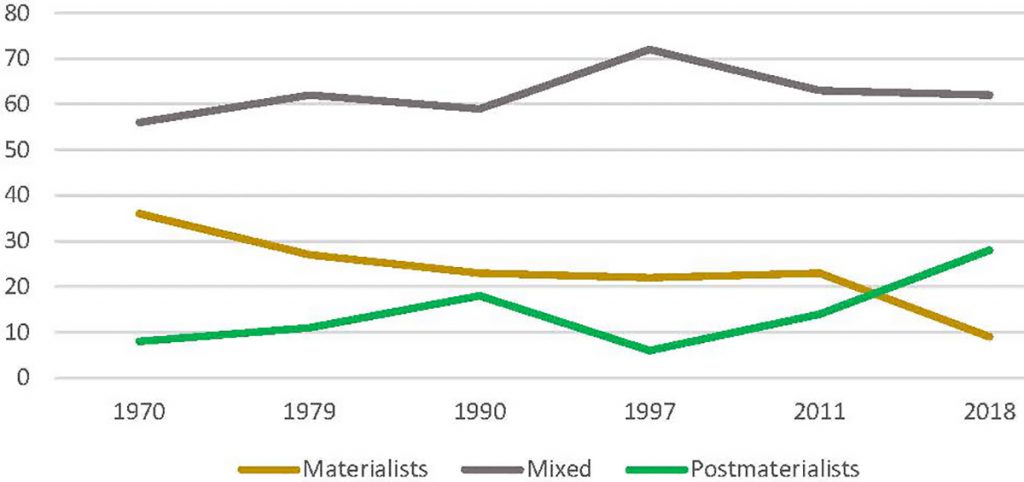

In our new book, The Modern British Party System, Paul Webb and I explore UK party politics using the tools of comparative politics. And we note that (as in many other Western liberal democracies) the balance in Britain is shifting toward postmaterialism, although we also emphasise that the majority of the population continue to display a mixed orientation. See Figure 1 above.

This, and the fact that some 41% of those classified as ‘mixed’ (and 44% of those classified as ‘materialist’) explicitly say they prioritise the economy over environmental protection are two reasons why the Johnson government (and its successors) will have to continue to work incredibly hard to persuade people of the necessity of sometimes expensive and disruptive change if the UK really is to reduce its emissions.

Johnson will have to continue to work incredibly hard to persuade people of the necessity of sometimes expensive and disruptive change if the UK really is to reduce its emissions

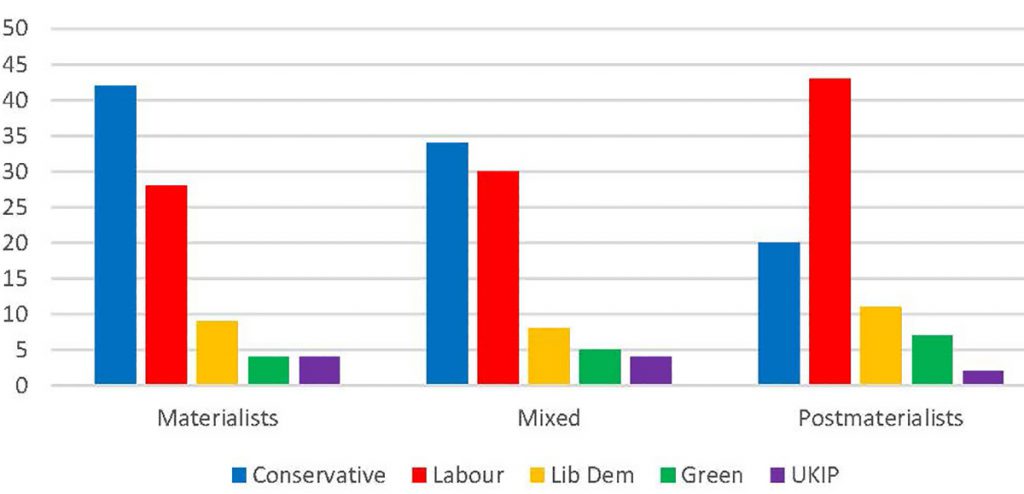

However, as we also note, there is an obvious connection between people’s value orientations and their choice of party – see Figure 2 below. All of which poses a dilemma for a Prime Minister with normally supportive newspapers nipping at his heels on net zero – especially if one of them, the Telegraph, is read by a third of ordinary Tory party members (as revealed by another recent book of ours, Footsoldiers: Political Party Membership in the 21st Century, co-written with Monica Poletti).

The situation is by no means as simple as ‘Vote Blue, no to Green’. But Boris Johnson clearly needs to do a far better job than he has done so far to convince his very own Conservative supporters, both in the media and up and down the country, that net zero should be one of their top priorities, and not simply a ‘nice to have’.