In 2015, Austria took in almost 90,000 asylum seekers – the third-highest number in Europe that year. The government housed asylum seekers in areas with little experience in welcoming refugees. These areas subsequently saw a backlash against refugees in particular, and against immigrants and Muslims in general, write Markus Wagner and Lukas Rudolph

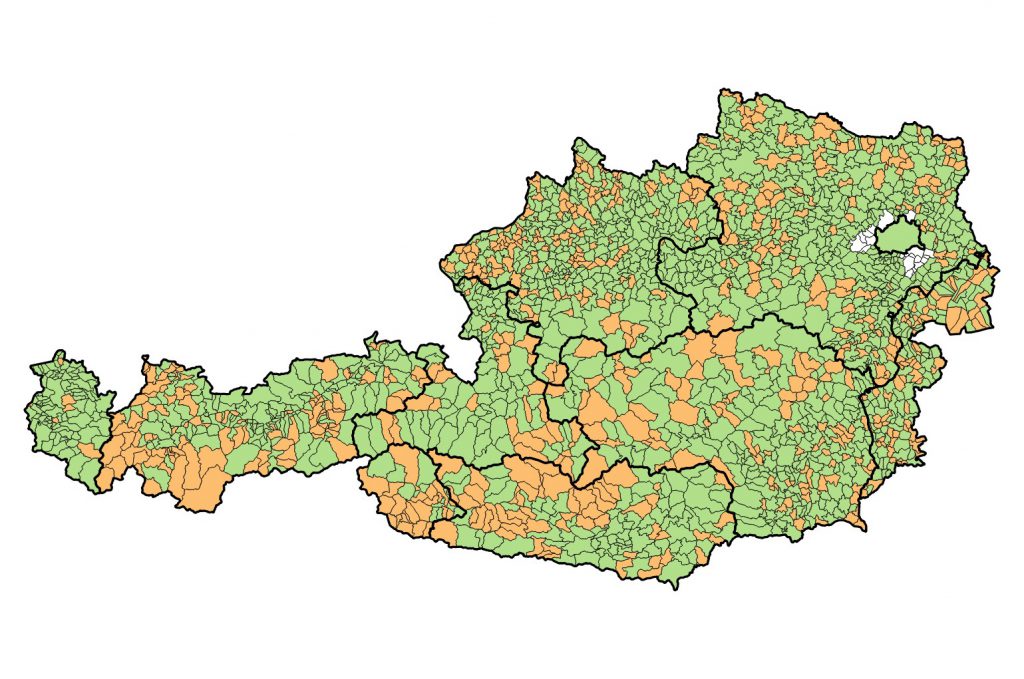

In a recently published study, we compare areas in Austria that took in asylum seekers as part of the so-called refugee crisis with those that did not. As shown in the Figure below, many areas received asylum seekers, shaded green here. However, many areas (shaded orange) all over Austria did not take in asylum seekers. Hence, we can compare how these municipalities differed in their reaction to the influx of asylum seekers.

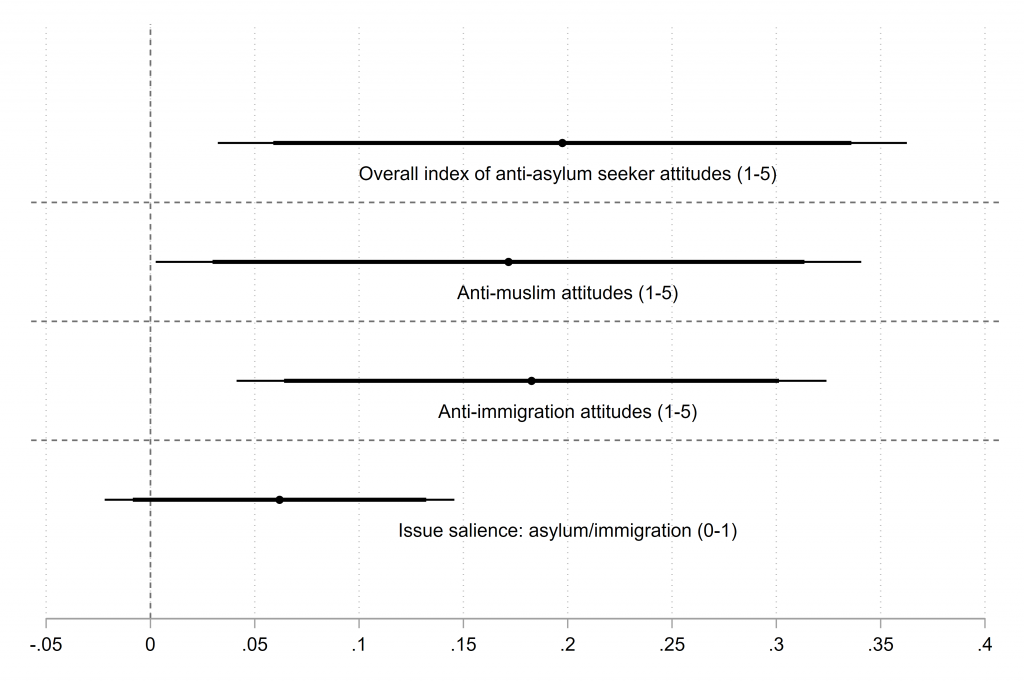

Figure 2, below, shows survey data from the Austrian National Election Study 2017. We can see that people in areas which received asylum seekers had substantially more negative anti-asylum attitudes two years after the migration crisis than areas that did not take in asylum seekers.

people in areas which received asylum seekers had substantially more negative anti-asylum attitudes two years after the migration crisis than areas that did not

The backlash did not just concern the narrow group of asylum seekers. Attitudes towards various outgroups worsened. By 2017, anti-Muslim and anti-immigration attitudes were also substantially higher in the areas that received asylum seekers (see Figure 2).

Which local residents reacted most negatively? Male, older and less-educated people were most likely to develop more hostile attitudes. Areas with few foreigners and strong radical right support also experienced strong negative reactions.

This attitudinal backlash towards asylum seekers and associated groups also had political consequences. In particular, voters in areas housing asylum seekers were 10% more likely to want to vote for the radical right Freedom Party.

The radical right campaigned particularly intensely in these areas, perhaps in an effort to exploit or even feed this backlash.

Housing asylum seekers can thus lead to a substantial backlash from the local population. Allport’s contact theory suggests dislike of minorities declines once there is more interaction with the majority group. At first glance, we might imagine that backlash from local populations disproves Allport's theory. The kinds of contact that can reduce prejudice, however, often do not take place.

People in areas housing asylum seekers took note of the recent arrivals. But they did not have closer contact with asylum seekers than people in areas without refugees. Asylum seekers were outsiders wherever they lived, and the native population perhaps often saw them as different and threatening. This creates a context that is conducive to backlash.

Asylum seekers were outsiders wherever they lived, and the native population perhaps often saw them as different and threatening

It is unlikely that the backlash occurred because these areas were already more sceptical of outsiders before the crisis. So many asylum seekers arrived in 2015 that communities could not choose whether to accept them: they were simply housed wherever space was available. We also used a statistical method – entropy balancing – to ensure that the communities we compare are similar in every relevant way, apart from whether they received asylum seekers or not.

Our findings apply mainly to less populous districts, since all urban areas in Austria received asylum seekers in 2015. These areas are especially relevant, because it was in rural areas that the radical right did especially well in the 2017 elections. It is in these areas, therefore, that backlash was most consequential.

Yet housing asylum seekers does not necessarily lead to a backlash. Much depends on prior local experience as well as how the government implements and communicates its policies.

Policy makers need to be aware that there may be a backlash to policy decisions. They must consider carefully any decision on how to house asylum seekers. Accompanying policies should facilitate contact and involve a clear communication strategy emphasising the need for, and benefits of, welcoming refugees.

Moreover, mainstream politicians should be aware that some political actors, particularly on the radical fringe, may take advantage of the backlash potential and campaign heavily in these areas.