In the European Parliament, ‘delegations’ are formal groupings of Members who maintain inter-parliamentary relationships. At recently held constitutive delegation meetings, the gendered allocations of leadership positions revealed a complex picture. Cherry Miller and Lorenzo Santini find that, despite initiatives to improve gender representation, there has been a decline in the number of ‘head’ women delegation chairs

Women and EU leadership is a burgeoning topic, with European Commission President Ursula Von Der Leyen seeking a gender-balanced team. Meanwhile, the President of the European Parliament (EP), Roberta Metsola, used her acceptance speech to emphasise parliamentary diplomacy, a key theme in the recently inaugurated 2024–2029 legislature (EP10).

An underexplored set of actors linking these two developments are EP delegation chairs. Delegation chairs are key performers of EP diplomacy. Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) maintain international relationships with parliamentarians and civil society. The Conference of Presidents can authorise ad hoc missions for major political or legislative events. As ‘embassies on the move’, delegations possess soft-power tools, such as recommendations and persuasion.

Delegation chairs are key performers of EP diplomacy who possess soft-power tools such as recommendations and persuasion

Unlike other EP institutional positions, Delegation Bureaux comprise one chair and at least one or two vice-chairs, elected for five-year mandates. Some parliamentary assemblies have larger Bureaux. The African, Caribbean and Pacific Bureau, for example, has 11 vice-chairs. Chairs sit in the Conference of Delegation Chairs, a governing body coordinating delegations’ work.

Chairs’ formal roles include presiding over inter-parliamentary and ordinary meetings, drafting recommendations with the Bureau and reporting to coordinating committees dealing with external affairs. Only chairs can hold press conferences and sign joint statements with counterparts, representing the EP’s official positions. Informally, alongside the Secretariat, chairs coordinate the practicalities of inter-parliamentary delegation meetings.

Delegation chairs may facilitate gender equality promotion. In the 2019–2024 legislature (EP9), the Conference of Delegation Chairs had feminist leadership. Inma Rodríguez-Piñero, an MEP from the centre-left Socialists & Democrats (S&D), introduced an intra-delegation gender mainstreaming system of appointees, informally supported by chairs. Chairs affect delegations’ culture, which may have an impact on attendance and membership.

Delegation chairs can facilitate the promotion of gender equality, and impose gender quotas on delegation speaking lists

Delegations can ask the EP President to hold a debate on urgent breaches of human rights, democracy and rule of law. Such debates may result in urgency resolutions, which are important for gender equality defence. In new delegations, the Bureau agrees draft rules of procedure with the Secretariat.

Informally, chairs can impose a gender quota on delegation speaking lists. Other efforts include liaising with EU ambassadors, advocating for women’s rights in parliamentary elections in the partner country/region and holding discussions with international women parliamentarians before official meetings take place.

Delegation Bureaux follow the same rules of formation as Committees. Right of centre groups widely contested the EP10 nominations as a result of new rules adopted in July 2024. Former EP9 rules from November 2023 forbid same-gender and same-nationality Bureaux. New Rule 219 stipulates that the chairs and first vice-chairs 'shall not be of the same gender', and 'gender balance shall also apply to the other members of the Bureau'. Several vice-chair elections were postponed because political groups did not respect the gender requirement.

A new rule stipulating that chairs and first vice-chairs cannot be the same gender, met resistance from right of centre groups

Resistance to Rule 219 came from Patriots for Europe (PfE), a far-right sovereigntist political group, and the third-largest in the EP. They argued that if the EP can ignore the d’Hondt system – that is, the proportional system for allocating positions – then it can ignore Rule 219. Meanwhile, centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) delegation chair Andreas Schwab noted that postponing elections was 'a bit ridiculous'. Another EPP member, Daniel Caspary, jested about changing gender annually. A non-attached MEP, Grzgegorz Braun, critiqued a ‘gender agenda’.

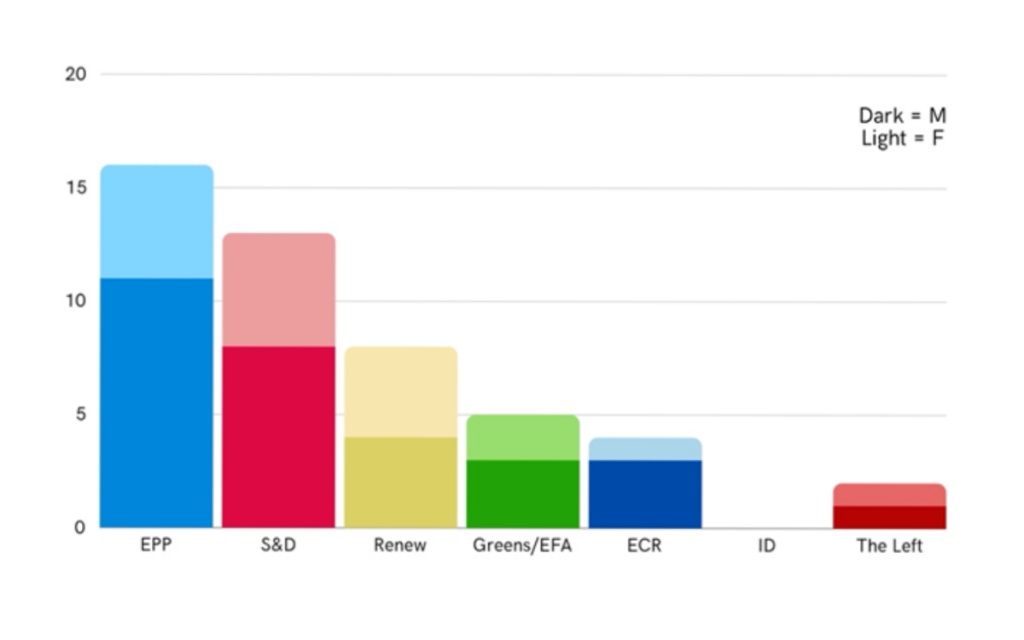

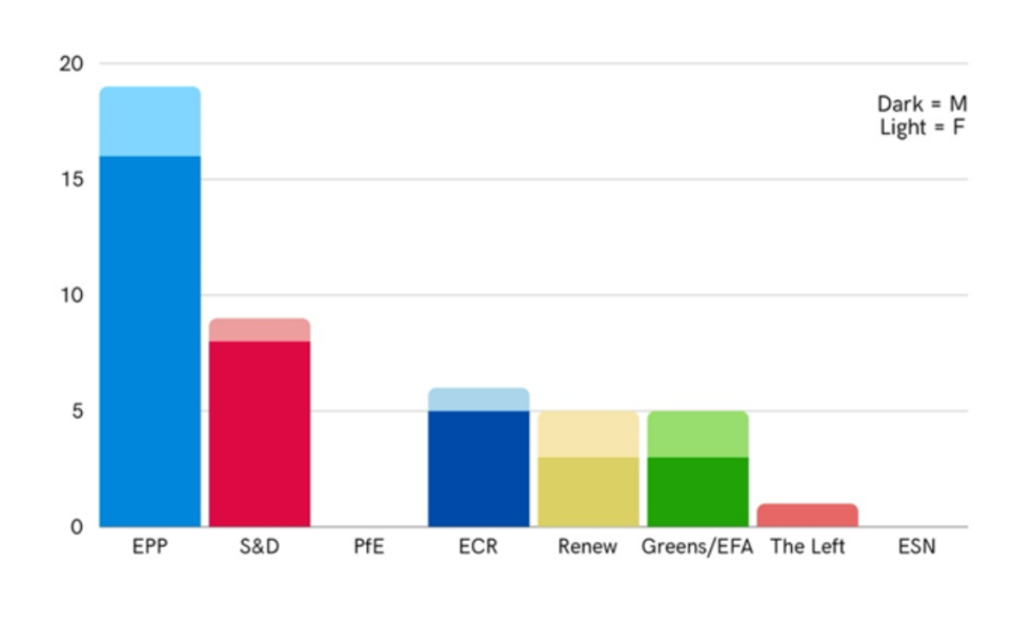

Beneath these contestations, we find that the share of head women delegation chairs actually dropped from 36% (EP9) to 22% (EP10). In EP9, male MEPs chair 10/14 of the biggest delegations (>20 MEPs). This trend continued in EP10, in which male MEPs chair 11/14 of the largest delegations. Chair of the Delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean, however, is assigned ex officio to EP President Roberta Metsola. In EP9, 6/19 chairs serving their first mandate were women. In EP10, this figure is similar at 3/13, but with fewer MEPs in total.

Turning to political groups, during EP9, Renew and The Left had the highest proportional share of women’s representation in all positions. The only European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) woman MEP, Jadwiga Wiśniewska, served simultaneously as chair and second vice-chair of three interrelated delegations. Rule 219’s effects are visible in EP10. While male MEPs dominated most chair positions by group, some groups, such as S&D (10/10) and Greens/EFA (4/4) have, to meet the requirement, nominated only women MEPs to first vice-chairs.

In EP9 and EP10, women are better represented as bilateral delegation chairs. Meanwhile, men are overrepresented as chairs in parliamentary assemblies and interparliamentary committees.

Membership of intra-parliamentary equality bodies provides some insight into how chairs might lead. In EP9, only two delegation chairs were full sitting members of the Women and Equalities Committee, FEMM. EP10 has Giuseppina Princi (S&D) and former FEMM members. In EP9, two chairs were co-Presidents of the Anti-Racism and Diversity Intergroup and 12 chairs were LGBTQI intergroup members (data unavailable for EP10). However, non-sitting FEMM members have pursued feminist delegation leadership.

Formally, delegation chairs are allocated through informal negotiations between the political groups, under the d’Hondt method. Informally, a cordon sanitaire – a refusal to cooperate with a party – was in 2024 placed around PfE, but not ECR, following potential concerns that these groups might unite. Groups used two tactics to deal with the Conservatives and Reformists. First, S&D, Greens/EFA and The Left issued statements of non-support, without proposing counter-candidates nor requesting secret ballots. A second tactic was to request a secret ballot; however, votes in the Delegation for Relations with the Maghreb countries, for example, showed abstentions. In the constitutive meeting of the Delegation to the Africa-EU Parliamentary Assembly, where Nicolas Bay (ECR, a former Europe of Nations and Freedom Group Co-Chair) was elected third vice chair, the procedural term ‘vote by acclamation’ was an ambivalent one.

Women’s parliamentary leadership in external affairs is a neglected area of analysis. Of course, women’s nominal participation in parliamentary bodies does not guarantee that they have a feminist mindset. But women may be symbolically important. Although they operate with some constraints, feminist delegation chairs may yet shape new trajectories of parliamentary diplomacy.