Violent local conflicts over land and resources are taking place almost exclusively in civil war-affected societies. Claudia Wiehler and Sebastian van Baalen argue that analysts and peacebuilding practitioners therefore need to involve civil war parties in communal conflict management and resolution — and view them as potential conflict management partners

The climate crisis is escalating and already causing massive disruptions to livelihoods across the globe. One feared downstream effect of the climate crisis is the outbreak and intensification of violent local conflicts between loosely organised groups over land and resources.

The perspective that climate change exacerbates communal conflict is important. However, it overlooks that these conflicts mostly take place in contexts also embroiled in violence between governments and rebel groups

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, communal conflicts kill thousands of people each year. Often, they leave massive destruction in their wake. Inter-communal violence in Mali in 2018, for instance, killed over 200 civilians in the Mopti region alone. The violence drove thousands from their homes and caused widespread hunger.

The perspective that climate change exacerbates communal conflict is important. However, this perspective overlooks that these conflicts take place almost exclusively in countries also engulfed in civil war between governments and rebel groups.

The concurrence of communal violence and civil war has important implications for how analysts and peacebuilding practitioners need to view such violence. We conducted research on wartime communal conflict in Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria. Based on this research, we have mapped communal conflicts as embedded in civil war. Here, we highlight two implications for managing and resolving such conflicts.

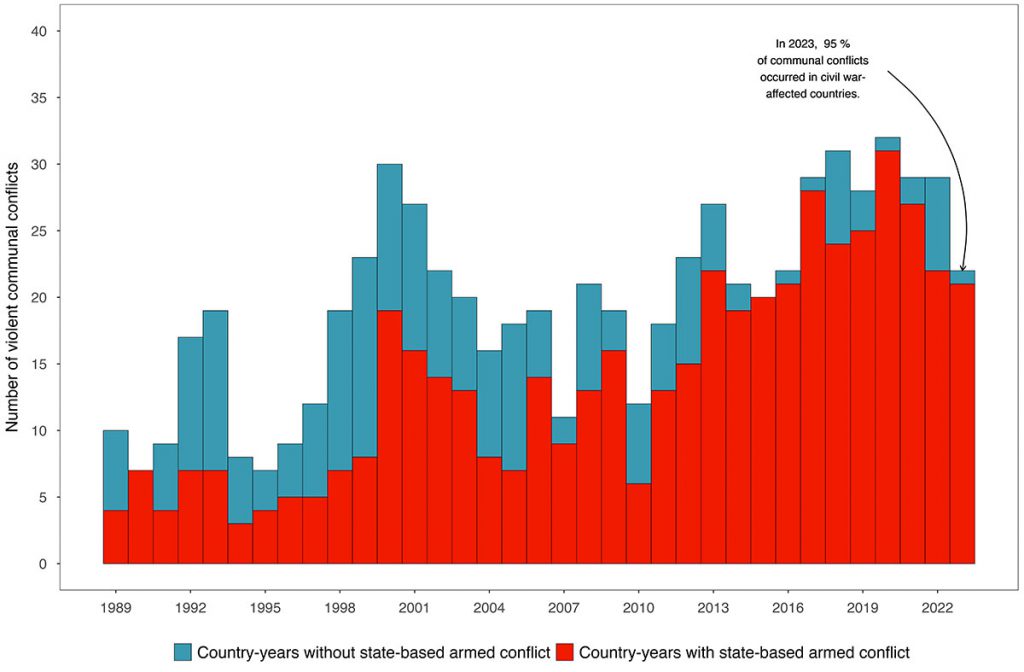

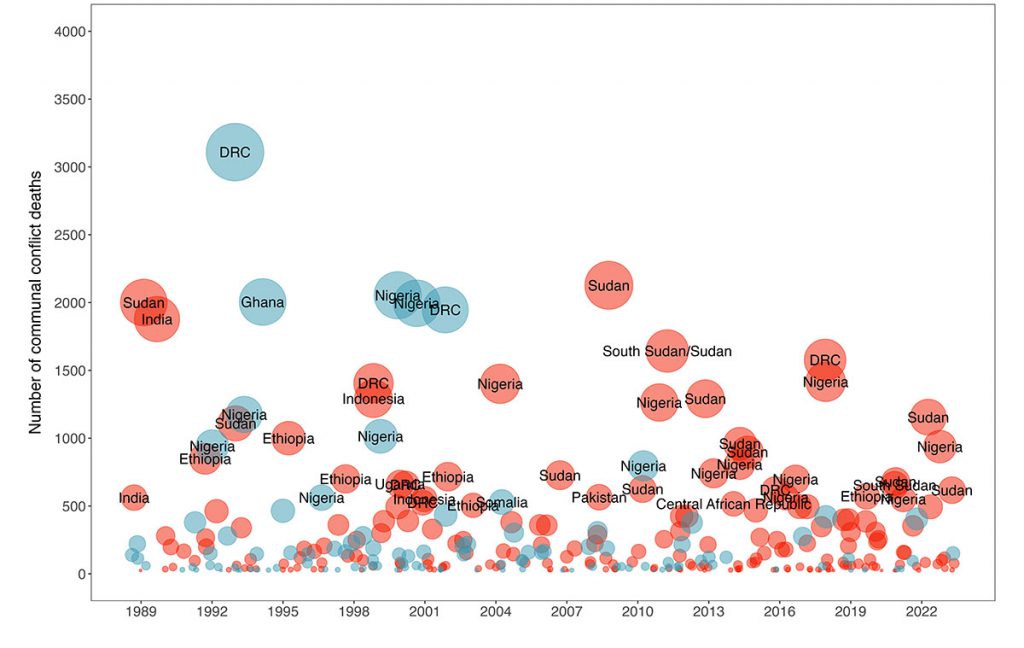

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program collects data on organised violence globally, and maps civil war and communal conflict deaths. Since 1989, the share of communal conflict deaths recorded in civil war-affected countries has soared from 49% in 1989–2006 to 88% in 2007–2023. In 2023, 95% of all communal conflicts unfolded in civil war-affected societies, including Sudan, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Myanmar. Nigeria, for instance, is grappling with a prolonged civil war against the violent extremist groups known as Boko Haram. At the same time, there are many communal conflicts in Nigeria, including between sedentary farmers and nomadic pastoralists.

The concurrence of civil war and local conflict is not surprising. Civil wars give rise to many structural drivers of conflict, such as economic recession, resource scarcity, and large-scale displacement. Civil wars also erode the state’s monopoly on violence, thereby creating a security dilemma between rival communities. In addition, civil wars transform social fabrics by empowering young, violent actors at the expense of traditional authorities. All this leads to the breakdown of established conflict management mechanisms.

Yet, the relationship between local conflict and civil war is more complex. Peacekeeping operations deployed to help end civil wars can have a positive side-effect of reducing communal tensions. Rebel groups can mediate in, and thereby manage, conflicts between communities.

Spiralling communal conflicts can undermine attempts to settle civil wars. The massive displacement caused by civil war can shift communal conflicts to other areas, or suppress them completely.

Local conflicts in civil war do not escalate everywhere at the same time. Peacebuilding practitioners need to pay attention to when and where conflicts escalate

Moreover, local conflicts in civil war do not escalate everywhere at the same time. This demands deeper insights on the spatial and temporal patterns of spillover effects. Peacebuilding practitioners need to pay close attention to when and where conflicts are likely to escalate.

We lack understanding of the more complex interlinkages between communal conflict and civil war. Systematic analyses of the links between the two phenomena are still rare. Nevertheless, our research on wartime communal conflicts points to two key implications for the management and resolution of these conflicts.

First, the embeddedness of contemporary communal conflicts in civil wars stresses the need to scrutinise the involvement of the civil war parties in these conflicts. State security forces, rebel groups, and militias often play a critical role in instigating communal tensions, arming communal militias, and accompanying perpetrators of communal violence.

In Mali, for example, the concentrated effort by Islamist armed groups to recruit among the pastorialist Peuhl has 'inflamed tensions' with the Bambara and Dogon communities. During the Ivorian civil war, our research shows that militias fighting on behalf of Laurent Gbagbo's government played a critical and active role in fuelling communal conflicts. Likewise, Nigerian state governments supported vigilantes of farming communities against so-called bandit militias. These militias, in turn, were wooed by Boko Haram.

Civil wars and communal conflicts should be addressed as interlinked phenomena

Armed actors play a prominent role in inflaming and sustaining communal conflicts. We should therefore address civil wars and communal conflicts as interlinked phenomena. Analysts need to look beyond the main parties to communal conflicts and consider what role other armed actors assume in those conflicts. Peacebuilding practitioners must assess the implications of the interlinkages for the effectiveness of their interventions.

Civil war parties can thus play a significant role in triggering and sustaining local conflicts. Local conflict management can be difficult if these actors are excluded from the process. Government forces and rebel groups embroiled in communal conflicts have the capacity to singlehandedly ruin any agreement.

Excluding civil war parties from conflict management precludes those parties from helping to prevent, curb, and resolve communal violence

Excluding the civil war parties also overlooks the possibility that they can take active steps to help prevent, curb, and resolve communal violence. Our recent research on the Ivorian civil war demonstrates how the Forces Nouvelles rebels took measures to ease ethnic tensions and manage violence, including by mediating local peace agreements.

Far from all armed groups make suitable partners for conflict management. However, armed groups seeking legitimacy, who strive to improve their international reputation and build positive relationships with civilians, have at least some incentives to become local peacemakers.

Studying and raising awareness about how climate change affects the risk of communal conflict is an important task. However, our research demonstrates that doing so without considering the fact that contemporary communal conflicts are largely a wartime phenomenon risks missing the broader context in which such violence takes place, including pitfalls and opportunities for conflict management and resolution.

Definitions: The authors did not offer a definition of civil war, nor a discussion of how the two cases (Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria) and other countries mentioned are perfect case studies of civil war. This would be necessary before the linkage to communal conflict could be understood. Assuming that fighting Jihadist violence is what makes Nigeria a case of civil war, then would the same be said of all the countries which subscribed to the “global war on terror”? It would have been an interesting discussion to see how authors define/understand civil war and then see how Nigeria and Cote d'Ivoire fit such model to allow for comparison.

If communal conflicts are “violent conflicts between informally organised groups that share a common identification along ethnic, clan, religious or tribal lines” – then is Boko Haram not conceptually a communal conflict?

Co-Occurrence is not Causality: The authors draw from the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict to argue that communal conflicts are occurring in countries facing civil war (Cote d’Ivoire is missing in this chart though). But there is no theory as to how the two forms of conflict could be linked, except for the authors’ caveat that “We lack understanding of the more complex interlinkages between communal conflict and civil war”.

In a large country like Nigeria, it is possible that the Boko Haram can co-occur along with religious, ethnic, natural resource and other forms of conflict without them being linked. Perhaps, the only red-thread running through the myriad of conflicts in Nigeria is the involvement of the same national armed forces. Can understanding of Boko Haram inform the mediation of petro-resource conflicts in the Niger Delta?

Chicken before egg? It is possible to reinterpret the same data provided by the authors to argue instead that civil wars are occurring in countries already facing communal conflicts. If Boko Haram conflict is what makes Nigeria a civil war case, then it is possible to argue that it is one of the youngest conflicts in Nigeria. The communal conflicts in the North Central part of the country tend to have long history, dating to over fifty years. Boundaries set by colonial or military governments; pattern of representation in governance since 1999; dispute over indigeneity (first enshrined in the constitution in 1979) are some of the main causes discussed.

Do the recommendations fit the cases? The authors recommended civil war parties “as potential conflict management partners” in resolving communal conflict, but apart from one sentence on Forces Nouvelles they did not illustrate what this could look like, say in Nigeria. It could be possible that Forces Nouvelles helped mediate communal conflict, but there is need to consider what made them succeed, on that occasion, before offering them and other civil war parties as a model mediation “partner”.

I like the theories of Franz Jedlicka, who has analyzed the "culture of violence" in the countries of the world (Culture of Violence Scale 2023). He argues that armed conflicts nowadays are only started by countries "where already beating children and women is common" (because there are no laws to protect them). I can´t help thinking he is right, and peacebuilding efforts must also have an eye on children´s rights.

Angelica Briding