It is a common assumption that autocrats have no incentive to redistribute income and wealth. Not so, says Lars Pelke. Uncertainty about the outcomes of autocratic elections can incentivise dictators to redistribute wealth, especially when the incumbents’ ruling coalition is inclusive

Autocracies use elections to gather information on elites and citizens’ preferences, and to create an image of legitimacy. It is also evident that autocracies differ in their levels of electoral uncertainty.

Vietnam, a closed autocracy, permits no electoral competition. Belarus, on the other hand, does hold elections, but significant irregularities affect the results. The winner is, in practice, determined before the elections. We call this a hegemonic multiparty autocracy.

In contrast, in the competitive multiparty autocracy of Singapore, elections allow for substantial competition between the autocrats’ incumbent party and the opposition. Moreover, in Singapore some degree of freedom of expression is guaranteed (although restricted by Covid-19 measures in 2020).

This is not to suggest that autocratic elections achieve democratic standards. It is, however, important to note that different autocracies have different levels of certainty that they will win elections. Autocrats and their ruling elites can also make mistakes.

how far incumbent parties are institutionalised, and the dictator's ruling strategies, help explain autocrats’ capacities to implement redistributive policies

Hence, it is hardly surprising that autocrats around the world provide different levels of public policies for their citizens. Electoral uncertainty can be an important incentive for dictators to use public policies, such as redistribution of income and wealth, to co-opt their own electorate and convince the electorate of opposition parties.

Two important features of autocratic regimes help explain autocrats’ incentives and capacities to implement redistributive policies. These are, firstly, the degree to which incumbent parties are institutionalised and, secondly, the dictator's ruling strategies.

One of the most distinctive characteristics of contemporary autocracies is that their rule relies on parties. Most autocratic regimes use parties for credible power sharing with their own ruling elites, and to broaden their support base.

However, these incumbent parties differ in their degree of institutionalised rule. What is important for the autocrat is that parties allow them to co-opt potential rivals and distribute economic benefits among members of the ruling coalition.

Yet the mere existence of political parties in autocracies cannot explain why redistribution varies among dictatorships. Rather, incumbent parties' internal constitution matters: party institutionalisation enables and provides incentives for authoritarian leaders to redistribute.

What is important for the autocrat is that parties allow them to co-opt potential rivals and distribute economic benefits among members of the ruling coalition

A second major difference between autocracies is the degree to which their ruling coalitions use inclusionary or exclusionary ruling strategies.

Inclusionary ruling strategies rely on a broad public support coalition. Such regimes integrate various social groups by using political and economic concessions to buy political support. This also works to decrease the likelihood of action against the status quo.

In contrast, regimes with exclusionary ruling strategies exclude societal and political groups from power. They do this by hand-picking people and limiting access to power. Such regimes actively restrict other societal groups' access to power.

The theory developed in my study for the Democratization journal predicts that the effects of party institutionalisation and ruling strategies are conditional on electoral uncertainty in autocracies.

First, inclusionary ruling strategies incentivise ruling elites to redistribute income. In contrast, exclusionary ruling strategies decrease the incentives.

the effects of party institutionalisation and ruling strategies are conditional on electoral uncertainty in autocracies

Second, when party institutionalisation is high, ruling elites have greater capacities and incentives to implement redistributive policies. Both mechanisms differ, however, depending on electoral uncertainty.

Through my research, I wanted to understand how electoral uncertainty influences redistributive policies in autocracies. To do so, I looked at various measures for income redistribution and social spending in autocracies between 1960 and 2015.

As noted, we can distinguish between closed autocracies, hegemonic multiparty autocracies, and competitive multiparty autocracies. These regimes differ in their electoral uncertainty and it is therefore likely that the effects of party institutionalisation and inclusionary ruling strategies will vary.

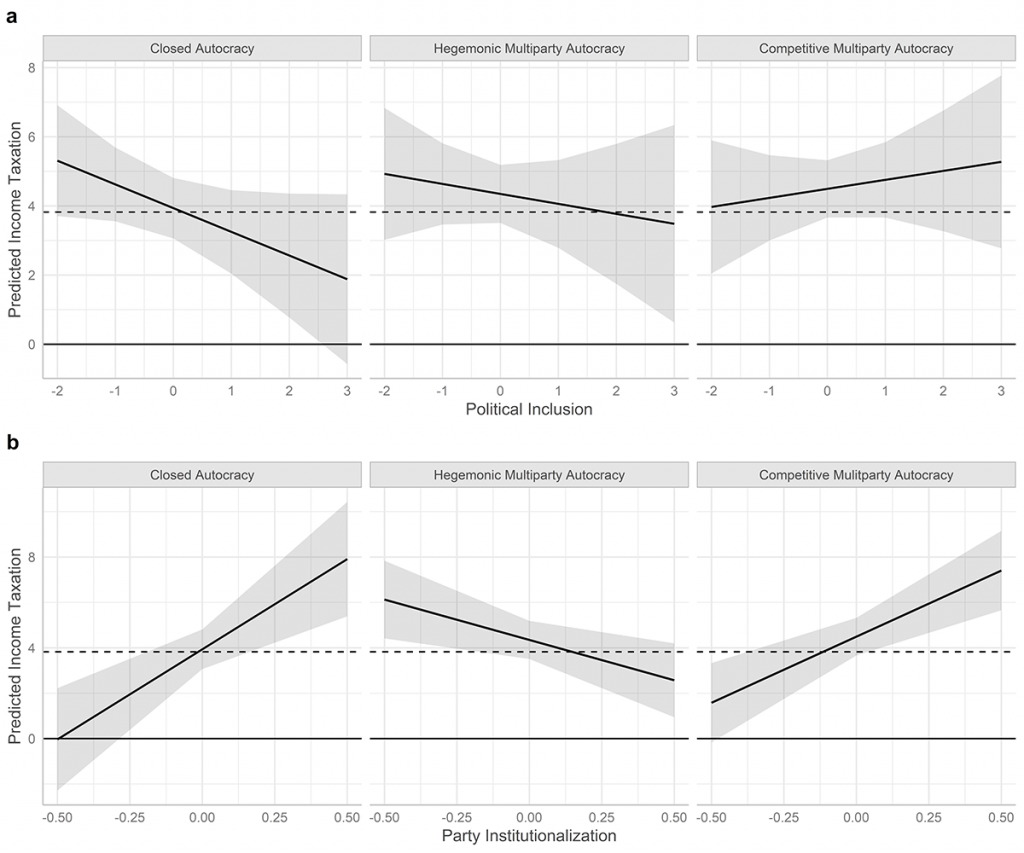

The graphs below show estimated effects of inclusion (top row), and party institutionalisation (bottom row) across regime types for taxes on income, profits and capital gains in % of GDP. Solid lines indicate the estimated effect. Shaded regions show adjusted 95% confidence intervals.

The top row shows how more inclusionary ruling coalitions have higher levels of income redistribution (measured here with income taxation) compared with more exclusionary regimes. But this is only true for regimes in which electoral uncertainty is relatively high (competitive multiparty autocracies). In these regimes, autocrats can misinterpret their chance to win elections. In regimes with low electoral uncertainty, more political inclusion is harmful for redistribution.

The bottom row indicates that autocracies with higher levels of party institutionalisation redistribute more than autocracies in which incumbent parties are less institutionalised. But once again, this is not valid for all autocracies.

In regimes with high levels of electoral uncertainty, the positive effect prevails. In regimes with multiparty but predetermined elections (hegemonic multiparty autocracies), party institutionalisation does not stimulate redistribution.

The positive link between party institutionalisation and more redistribution in closed autocracies is theoretically unexpected. Closed autocracies with strong parties seem to redistribute even when the electoral incentive is missing.

Overall, one can interpret the results as somewhat beneficial for citizens living in competitive multiparty autocracies. These regimes can have a redistributive advantage for their citizens. But they are advantageous only under two conditions: when the autocracy is politically inclusive, and when the ruling party has been institutionalised.

However, it seems clear that redistributive policies under an autocratic regime can have meaningful consequences for regime stability, and for citizens' political preferences.

This knowledge helps us better understand the conditions under which dictators use public policies for their own advantage.