In Switzerland, poor political representation of people with a migrant background is not simply the result of prejudice and deliberate penalising by voters. Lea Portmann and Nenad Stojanović show that it is also caused by voters systematically favouring native ingroup candidates

Their names are Atici, Barrile or Arslan and they stand out amid the rest of the members of the Swiss parliament, almost all of whom hold familiar, typically Swiss-sounding names. Why are people with a migrant background, across European countries, still so poorly represented in political office?

Prejudice and the deliberate penalising of immigrant-origin candidates may be an obvious reason. However, our research also finds evidence for another explanation: native voters tend to discriminate systematically in favour of native ingroup candidates.

Discrimination against minority groups doesn't only affect the life chances and well-being of individuals who belong to these groups. If people from disadvantaged minorities groups face discrimination in elections, it challenges the core principles of democracy.

If people from disadvantaged minorities groups face discrimination in elections, it challenges the core principles of democracy

The foundations of representative democracies rest on the idea that all persons, at least those who hold full political rights, have equal access to political bodies. The interests of each citizen should be adequately represented.

Traditionally, most research on political representation of racial minorities has focused on the United States. But scholarly focus is now turning towards populations with migrant backgrounds elsewhere, including Europe.

In a recent study, we explore electoral discrimination by distinguishing between two forms of discrimination. The first is outgroup hostility, where voters cast their ballot on the basis of hostility, prejudice, racism or negative stereotypes against minority candidates.

If voters systematically favour native candidates, this puts minority candidates at a disadvantage, too

The second is ingroup favouritism. Discrimination may occur even without hostility towards – and discrimination against – minority candidates. If voters systematically favour native candidates, this puts minority candidates at a disadvantage, too. The primary motive behind this form of discrimination cannot be hostility. Rather, it is an expression of a preference, identification, or positive stereotypes towards native candidates. It is discrimination in favour of majority candidates.

Our study used the Swiss electoral system to investigate discrimination in elections in depth. This setting also allowed us to capture the hitherto largely overlooked aspect of ingroup favouritism and discrimination in favour of native candidates.

The Swiss electoral system is a variant of an open-list proportional representation system. Voters have a variety of options to oppose or support individual candidates. First, they vote for a party list. They can then modify it in the following two ways:

Firstly, voters can give additional votes to candidates (positive preference votes). They can allocate as many of these additional votes as there are seats to be filled in their constituency (the canton) to candidates on the selected list, but also to all other candidates.

In addition, voters can distribute negative preference votes by crossing candidates off the party list. If they do so, the candidates lose the vote they would have received via the list.

In the Swiss electoral system, voters may discriminate in a candidate's favour by awarding him or her positive preference votes. By contrast, we find evidence for discrimination against minority candidates if voters are more inclined to allocate negative preference votes to said candidates in comparison to native ones.

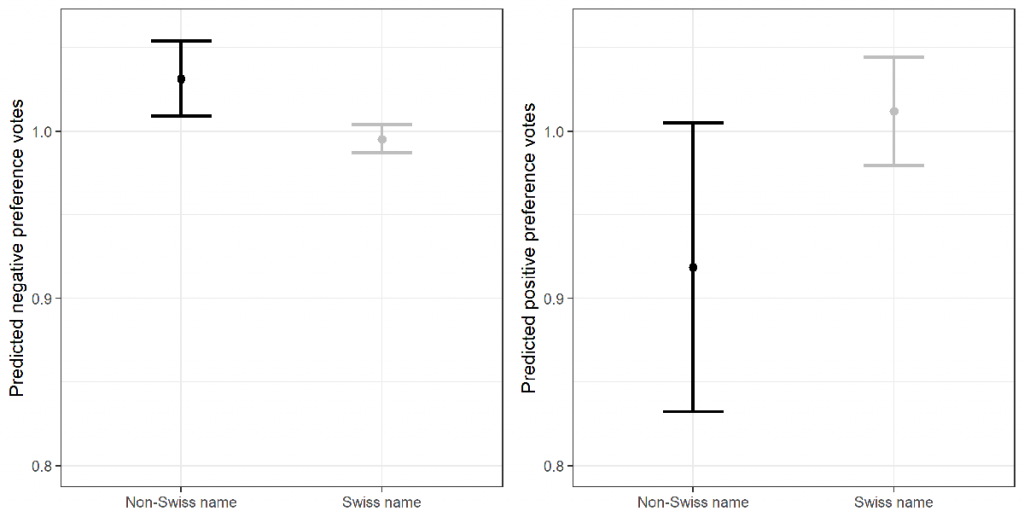

Our empirical analysis supports the assumption that Swiss voters discriminate against candidates with a migrant background. Focusing on candidate names, we find that voters are more likely to cross off candidates with non-typically Swiss names than similar candidates with Swiss-sounding names.

voters are more likely to cross off candidates with non-typically Swiss names than similar candidates with Swiss-sounding names

In an earlier paper, we presented similar evidence based on a Swiss local election study. In addition to this type of discrimination, candidates with a non-typically Swiss name face a second disadvantage. This is that they do not benefit from additional votes as much as those with typically Swiss names. This discrimination in favour of native candidates is marginally more pronounced than discrimination based on negative preference votes.

This finding is line with recently published studies on US and Italian elections. These studies find that ingroup favouritism plays a key role in voting behaviour.

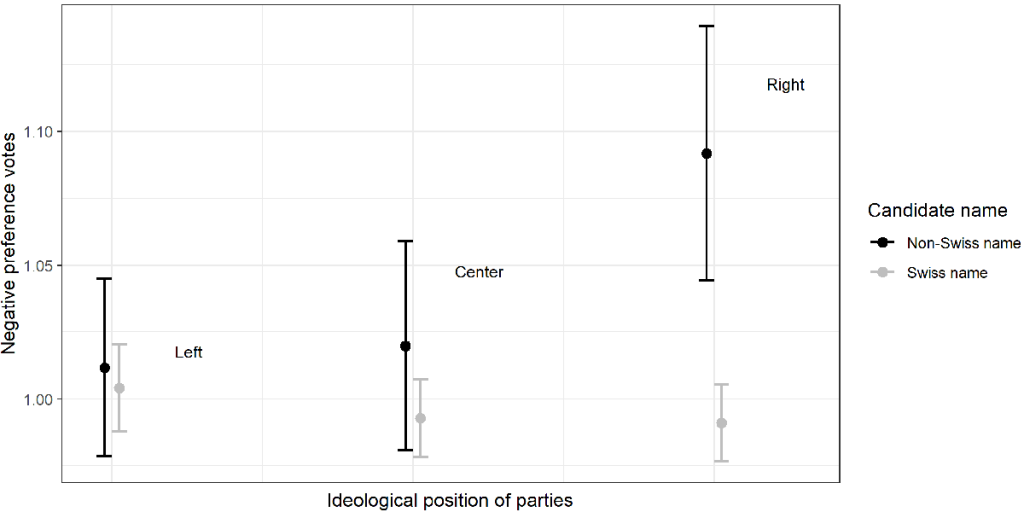

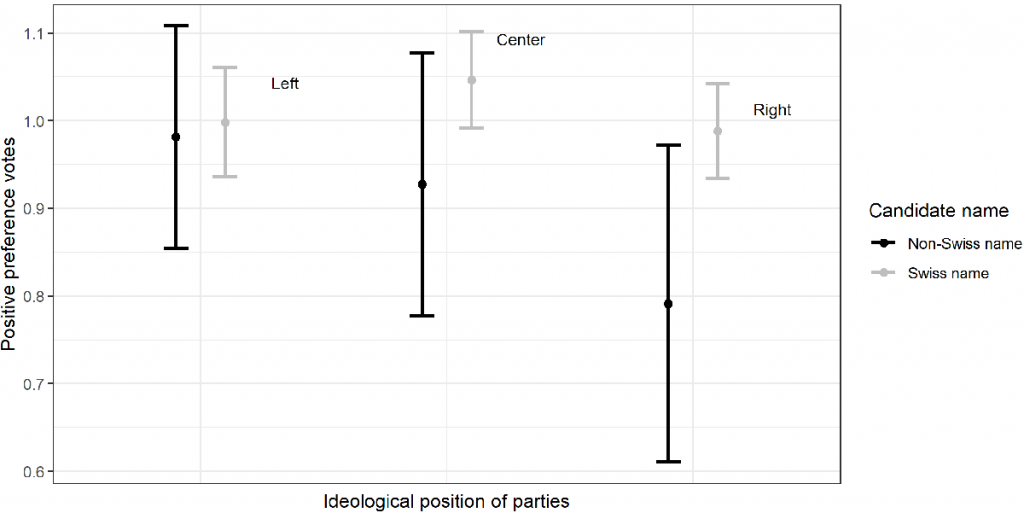

Do voters across the political spectrum engage equally in these two forms of discrimination? Our research reveals that targeted discrimination against immigrant-origin candidates strongly depends on the party list for which a candidate runs.

Such candidates receive substantially fewer negative preference votes than those with typically Swiss names. However, this difference in negative preference votes diminished among centrist voters, and is largely absent among left-wing party supporters.

We also find some differences between party lists regarding positive votes. But this type of discrimination is less clearly related to the ideological orientation of the list.

To combat discrimination in elections, we must address both outgroup hostility and ingroup favouritism. Measures aimed at reducing negative attitudes among some segments of the voting population must be combined with strategies to address ingroup favouritism. Increasing intergroup contact in society and politics may prove effective in reducing both forms of discrimination.

Initiatives to establish a more inclusive definition of who belongs to the national community are emerging in Switzerland (e.g. INES) and other countries. Such initiatives are important ways forward to dismantle boundaries between native and immigrant-origin populations, and to tackle ingroup favouritism.

This blog piece is based on research in the authors' recent Comparative Political Studies article Are Immigrant-Origin Candidates Penalized Due to Ingroup Favoritism or Outgroup Hostility?