Once the Russia-Ukraine war ends, perceptions of victory and defeat will affect not only the stability of those states' political regimes but the capacity of the state in the long term, says Luis Schenoni. Using examples from nineteenth-century Latin America, he argues that the effects of war outcomes on security and the rule of law will endure for decades

Charles Tilly’s famous claim that 'war made the state' suggests that wars necessitate (and lead to) the expansion of state capacity. In Europe, scholars accept that wars were a driving factor behind the development of national state bureaucracies, a process that culminated in the 'total wars' of the twentieth century by generating states of the greatest strength and scope ever seen. In the social sciences and humanities, we call this the 'bellicist theory' of state formation.

Since the second world war, however, aggression and wars of conquest have been forbidden, and it is less clear whether bellicist theory still applies. Conventional wisdom suggests that in conflicts which lacked the scale and intensity of European wars, conquest was not the endgame. Instead, states relied on foreign (rather than domestic) resources to fight them; war did not make the state. If this is true, wars should not now lead to the improvement of state capacity, as they used to do.

Ukraine’s war effort, largely reliant on foreign support, does not appear conducive to strengthening the state. But this seems to contradict what is happening on the ground

According to this theory, Ukraine’s war effort, largely reliant on foreign support, does not appear conducive to strengthening the state. But this seems to contradict what is happening on the ground. Is the Ukrainian state strengthening as a consequence of its war effort? And how might victory or defeat shape its future? These crucial questions must be answered before European capitals make key decisions on the support they are willing to supply, and what an acceptable peace could look like.

My book Bringing War Back In proposes a new interpretation of bellicist theory that might better make sense of how wars shape states. It argues that the critical factor is not just the occurrence of wars, but their outcomes. All contenders mobilise to some extent, triggering state-building. But only the winners should consolidate post-conflict efforts. Defeated societies are more likely to lose faith in wartime leaders and their state-building efforts, and to dismantle the state.

Defeated societies are more likely to lose faith in wartime leaders and their state-building efforts, and to dismantle the state

My book tests this argument against the history of Latin America, evidence from which shows how bellicist theory does apply beyond modern Europe. It is also a place where, despite frequent and severe warfare throughout the nineteenth century, all states survived. Since Russia and Ukraine, too, are likely to survive, I can compare the postwar effects of conflicts on winners and losers. War outcomes created divergencies that offer useful insights into regional development today.

Fighting wars, despite the foreign support needed to do so, does indeed build state capacity. All wars of sufficient severity trigger what social scientists call the 'extraction-coercion cycle'. To fund them, states must levy taxes, suppress internal dissent, and provide more public goods. Scholars argue that in places like Latin America and Ukraine, relying on foreign finance undermines state formation. But states facing severe warfare must always turn inwards to extract and coerce — and eventually repay their debts.

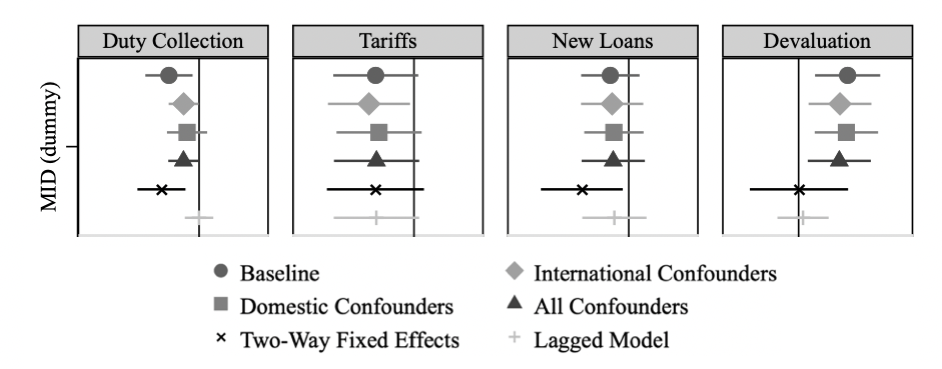

The diagram below shows the effect of Latin American militarised disputes 1830—1913 on custom revenue, tariff levels and the likelihood of acquiring a new foreign loan. The first three columns are all insignificant or negative, showing that even in this most likely region for third-party war financing, effort had to be made domestically by a devaluation of 20% on average (the last column). This imposed an inflationary tax of a similar magnitude on the local population.

Despite massive western support, one year into the war, Ukraine had devaluated the Hryvnia by 30% against the US dollar. The country faced an inflation rate of 25% and had introduced several new taxes. There is no such thing as a free war.

Taxing and conscripting the local population requires state coercion, a reality with which Ukrainians are all too familiar. In Russia, which lacks foreign support, the population feels such pressures even more intensely.

However, for Russia and Ukraine, dynamics of state formation are likely to play out very differently, depending on the terms of a future peace. If Russia wins, it may strengthen its institutions and consolidate power, much like Argentina and Chile in nineteenth-century Latin America.

If Russia wins, it may strengthen its institutions and consolidate power. A defeated Ukraine, by contrast, could struggle with legitimacy

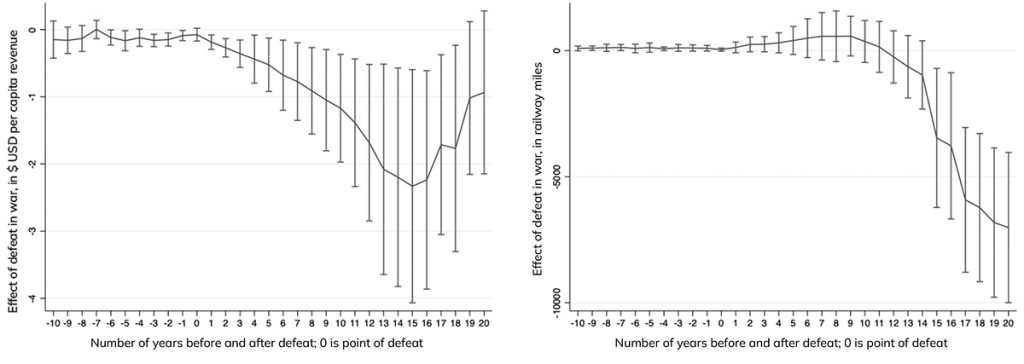

A defeated Ukraine, by contrast, could struggle with legitimacy. Its trajectory could be more akin to Peru’s after the War of the Pacific or Paraguay’s after the War of the Triple Alliance. Below, you can see the long-term effects of wars on the defeated states of nineteenth-century Latin America. The left-hand graph shows total revenue; the right-hand graph railroad mileage: both typical indicators of state capacity in those times.

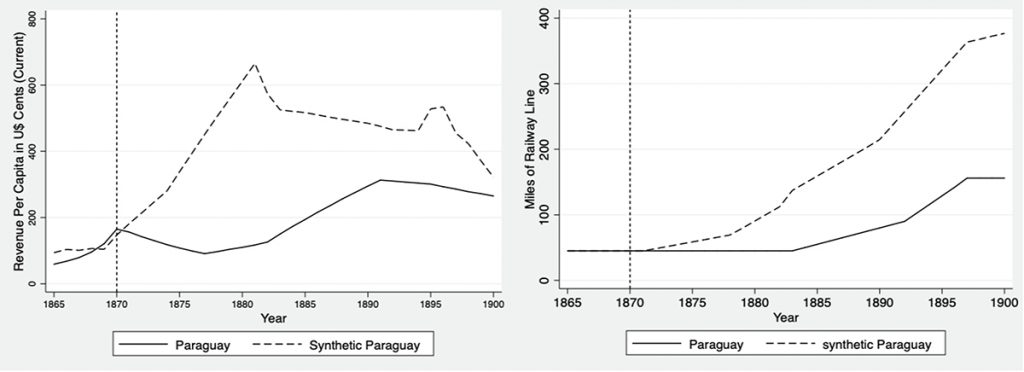

The models above show the average decline of capacity in states that lost wars. Losers tax less and invest much less than winners in critical infrastructure. The models below show the same by comparing a losing state (Paraguay), represented by a bold line, with how this state would have looked like had it not lost the war — the dashed line — in terms of its tax collection and capacity to build rail infrastructure.

These analyses suggest that the war's outcome is critical for the future of Ukrainian state capacity in the long term. While peace is of course desirable, European governments must carefully consider its implications. A peace that emboldens Putin, strengthens the Russian state, and undermines Ukraine’s in the long term could prove more perilous than continued conflict.