Innovative bureaucratic reforms are often explained by pointing to the motivations of individual bureaucrats or organisational culture. Yet, Niva Golan-Nadir explains how macro-level factors such as bureaucratic inefficiency, public criticism, and competition from NGOs also help initiate policy innovation and motivate managers into becoming entrepreneurs

The Chief Rabbinate of Israel is a state institution in a Jewish democratic state. It has a monopoly on granting kosher food certificates to public and private organisations. But the Rabbinate suffers from acute bureaucratic inefficiency, and has attracted harsh public criticism.

The Rabbinate faces increasing competition from private orthodox kosher food inspection organisations. In 2021, its Director-General, along with the Minister of Religious Affairs, initiated a reform allowing private organisations to issue kosher certifications. However, the Rabbinate remains the only body regulating all inspection organisations.

The High Court of Justice, the State Comptroller and the Knesset (Israeli Parliament) pointed out numerous failures caused by the Chief Rabbinate's poor policy design and implementation. The Rabbinate had failed to properly train supervisors or to regulate the profession of 'kosher supervisor' as full-time work. It had failed to require a threshold condition for engaging in the profession, or professional training. Moreover, it had failed to subject inspectors to periodic tests, or to employ supervisors in an orderly manner, with a proper wage.

Yet despite these institutional failures and the subsequent demands for change, the Rabbinate did not reform until alternative kosher supervision appeared.

Hashgacha Pratit, and the Tzohar Rabbis Organization, are alternative kosher supervision NGOs. Since 2017, they have challenged the Rabbinate's orthodoxy; for example, training women to become inspectors, which is not permitted by the Rabbinate. These inspectorates aim to create a cooperative relationship with store and restaurant owners and workers, based on shared Halacha values.

High Court certificate 6494/14 forbids such NGOs using the word 'kosher'. Every business inspected by these organisations therefore holds a publicly available binder detailing the kosher standards followed. Many private businesses now use these NGOs, rather than the official Rabbinate inspectors.

When he realised what had prompted such innovations, the Chief Rabbinate's Acting Director-General, Harel Goldberg, spotted an opportunity. In collaboration with Minister of Religious Services, Matan Kahana, he designed a reform opening the kosher inspection market to other Orthodox kashrut organisations.

However, Goldberg also determined that the Chief Rabbinate should remain the sole regulatory body with broad authority over all inspection organisations, thus protecting the Rabbinate's ultimate power.

What does this example tell us about which factors drive policy innovation?

Existing research into policy innovation deals mostly with the individual motivation of governmental bureaux heads. Such people are typically driven by ideology. They may sense their client needs welfare reforms, such as parental leave.

Other scholars highlight that motivation for policy innovation emerges from within organisations or as a result of inter-organisational competition.

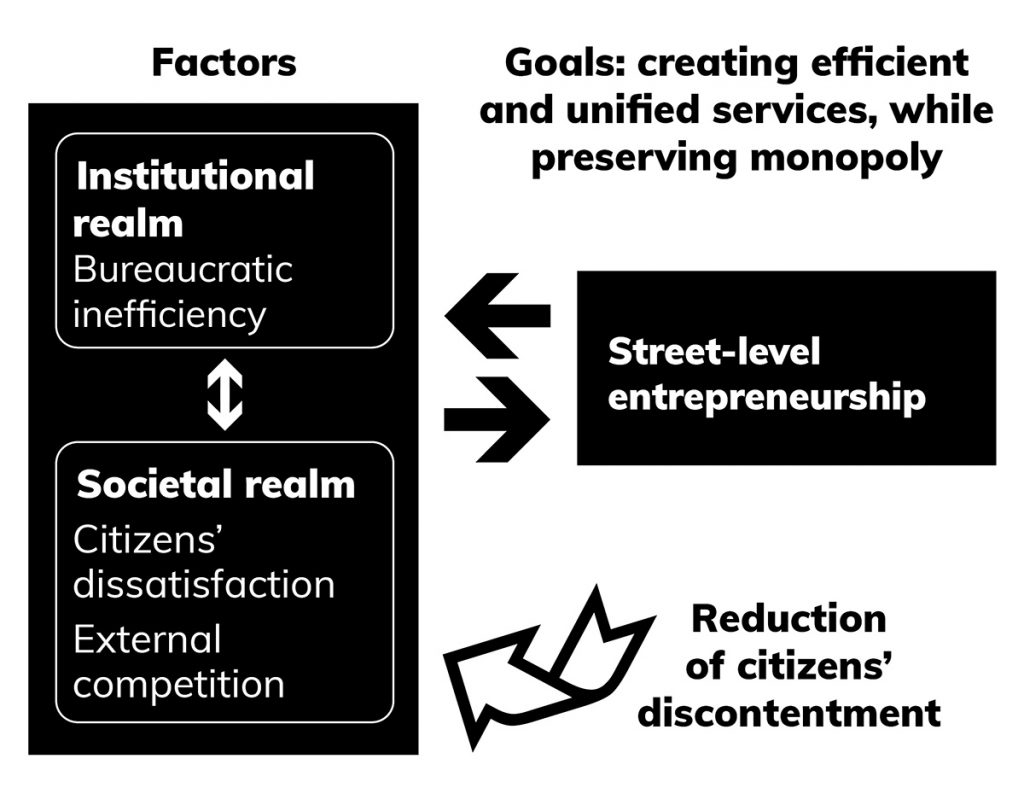

Bureaucratic inefficiency, public criticism, and competition from NGOs causes public dissatisfaction and demand for change. This forces bureaucrats of different ranks to develop entrepreneurial policy strategies. Hence, macro-level factors also contribute to policy innovation.

Pressure and demand for change affects high-level managers in particular. When they are subject to pressure, they develop strategies to improve service efficiency, while maintaining their organisation's ultimate control over service regulation.

But pressure from society also plays a role. Public opinion surveys by the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research on the Rabbinate and its kashrut (kosher food inspection) services reveal severe public criticism. In 2004, 55% of respondents said they had 'no trust or very little trust in the Rabbinate'. By 2009, that figure had risen to 58%, and by 2021, to 59%. In 2018, 66% of respondents said that they believe that the Rabbinate is corrupt. And in 2019, 64% agreed that the Rabbinate's monopoly on kosher food inspection 'should be revoked.'

In 2022, I conducted two surveys at Reichman University's Institute for Liberty and Responsibility. In the first, 65.3% of respondents said they 'completely or mostly agree' that the Rabbinate's monopoly on kosher food inspection should be revoked.

This leaves 31.5% who mostly disagree, or who disagree completely. Divided into levels of religiosity, 88.1% of secular respondents 'completely agree' or 'mostly agree', compared with 66% of traditional, 28.4% of religious, and 6% of ultra-Orthodox people. Results of my second survey mirrored these trends. Among respondents, 61.2% supported revoking the Rabbinate's monopoly, compared with 34.1% who 'mostly disagreed' or 'disagreed completely'.

The Rabbinate Director-General manages implementation, but not policy. The table below summarises his decision to reform Israel's Kosher inspection law.

| Action | Description |

| Initiative | For Harel Goldberg to lead a highly innovative reform in the kashrut system that is outside his managerial position |

| Burning issue | Goldberg's aspiration to reform kashrut began while he held a previous post, in 2017, when he established a large committee to suggest improvements to the malfunctioning and much-criticised system |

| Appointed to managerial position | When the former Minister of Religious Services, Matan Kahana, entered office in 2021, Goldberg was appointed Acting Director-General |

| Design | In multiple discussions and brainstorming sessions, Goldberg articulated the reform, identified difficulties, and reassured internal practitioners sceptical of the reform, while cooperating with the Minister |

| Team building | Harel Goldberg has created a professional, managerial think tank to follow each step in designing the reform; human resources, the Rabbinate's legal counsel and a representative of the rabbinical national kashrut department |

| Future implementation | Goldberg is directing the implementation of this reform |

| Legislation process | Minister Matan Kahana held official Knesset committee discussions during which Goldberg introduced several paths for reform. One was selected |

| End point | Law enacted in the Knesset via the rapidly legislated Arrangement Law, actualised January 2023 |

So, is managers' policy entrepreneurship a positive phenomenon in a democratic framework? If a manager feels their organisation's policies are being constrained, forcing them to provide substandard services, then yes.

This is important because democratic institutions are the building blocks of democracy, and the creators of good governance. Theoretically, a change in their design by a single agency might endanger the democratic institution's stability. Therefore, identifying what leads to entrepreneurship might allow institutions or organisations to manage managerial strategies with proper democratic checks and balances. They could foster innovation, while still protecting democratic arrangements.