Western countries repeatedly point to resettlement – the organised transfer of refugees to a safe third country – as a solution to persistent humanitarian crises. Yet, Philipp Lutz and Lea Portmann show how such resettlement can, paradoxically, be a way for states to legitimise limiting access to humanitarian protection

Over recent years, Europe has become increasingly worried about people seeking humanitarian protection. Governments in many countries have continuously stepped up efforts to prevent access for asylum seekers.

At the EU’s external borders, the deterrence imperative has now gained priority over the rule of law. Politicians and the media problematise humanitarian acts as a pull factor for further unsolicited immigration. This is starkly visible in the recent humanitarian crisis at the Poland-Belarus border.

In this context, an alternative access channel to humanitarian protection has gained increasing attention among policymakers in liberal democracies: resettlement. This instrument involves the transfer of persons in need of protection from their region of origin and offers secure residence status upon arrival. The process happens mostly in coordination through the UN Refugee Agency. This means that refugees receive protection without having to embark on a dangerous journey to arrive irregularly in Western countries where they would then seek territorial asylum.

By 2019, almost two-thirds of OECD countries had institutionalised annual quotas to regulate the resettlement of refugees

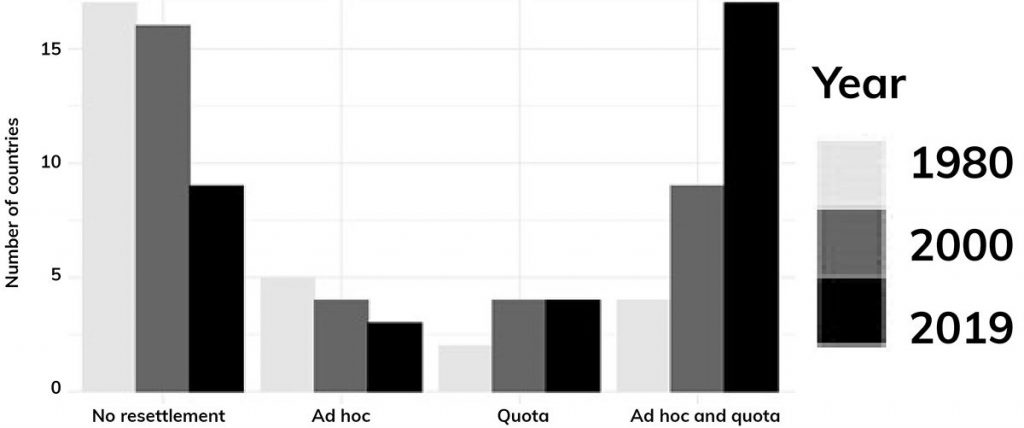

Increasingly, states are introducing or expanding their resettlement policies. They thereby either admit refugees on an ad hoc basis, through fixed annual quotas, or using a combination of both instruments. Our study of 33 OECD countries, published in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, reveals that in 1980 only 11 of them had resettlement policies in place. This number had more than doubled by the end of 2019, with 24 countries offering refugee resettlement. Almost two-thirds of the countries in 2019 had institutionalised annual quotas to regulate resettlement.

But why do states voluntarily admit refugees while simultaneously making costly efforts to prevent the arrival of asylum seekers? It is a state's obligation to examine asylum requests of individuals arriving on their territory. But the resettlement of refugees is an entirely discretionary act.

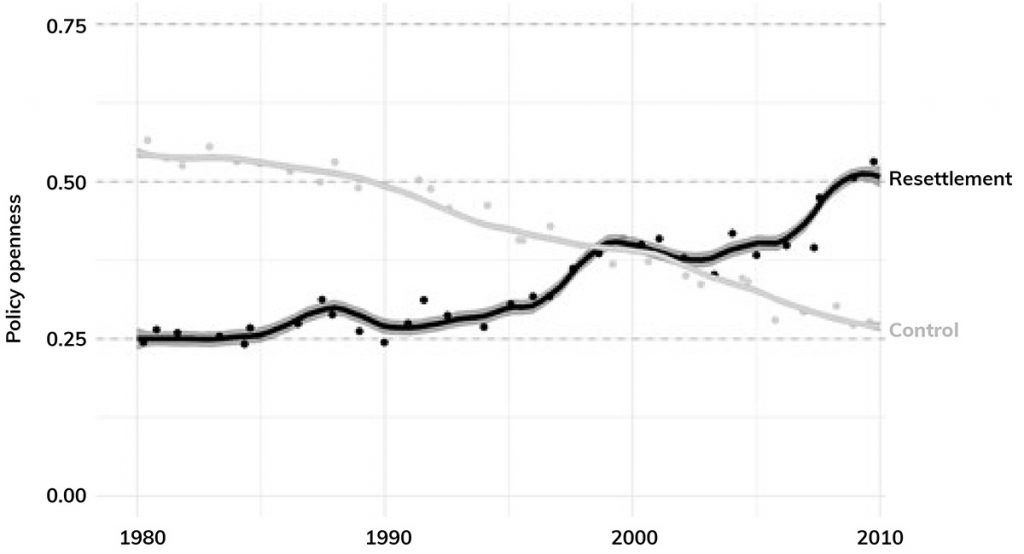

To shed light on this puzzle, we assessed the impact of resettlement policies on humanitarian protection. Our results demonstrate that the expansion of resettlement policies has had a negligible effect on effective admissions. Only a small number of refugees have benefited from these programmes.

states have combined the liberalisation of resettlement with more restrictive migration controls aimed at keeping asylum seekers out

Instead, states have combined the liberalisation of resettlement with more restrictive migration controls that aim to keep asylum seekers out. The approach towards asylum seekers attempting to reach Europe has become increasingly repressive. Despite this, governments in liberal democracies remain committed to the Geneva Convention and the right to seek asylum. Offering resettlement allows these governments to uphold their commitment to refugee protection despite an ever more restricted access to asylum.

Resettlement offers are falling far short of actual protection needs, and benefit only a small number of refugees. Thus, these policies do not only fail to contribute significantly to humanitarian protection; they also serve as a strategic instrument to keep overall refugee admissions at a minimum.

Over time, resettlement has increasingly become a strategic element of Europe’s migration management. An explicit combination of resettlement with border control regulations is included in the so-called EU-Turkey deal. Under this arrangement, governments offer resettlement spots in exchange for stricter enforcement of external border controls and the return of migrants already arrived in EU territory. Some European politicians envisage an ‘Australian model’ in which the government uses its resettlement programne to delegitimise irregular arrivals of asylum seekers as ‘queue-jumpers’ and ‘economic migrants’.

Europe’s response to humanitarian migration is caught in a ‘liberal paradox’. On the one hand, governments are eager to keep asylum seekers out of Europe to curb anti-immigration populism. On the other hand, liberal democracy demands a respect for human rights that includes the right to seek asylum.

resettlement promises a legal pathway to protection for vulnerable refugees, but it has not expanded overall humanitarian protection

Resettlement seemingly offers a way out of this dilemma. It allows governments to bolster their humanitarian credentials while legitimising the sealing of the EU’s border to asylum seekers. Although resettlement promises a legal pathway to protection for vulnerable refugees, its recent liberalisation has not expanded overall humanitarian protection. On the contrary, it has been used to legitimise ‘fortress Europe’. However, employing resettlement merely as a humanitarian alibi undermines its core purpose: offering an effective response to pressing humanitarian crises.