Trump may have scored a resounding win, but can he deliver the changes Americans voted for? Titus Alexander argues that the new political order challenges political science to help citizens make democracy work better

'The American experiment endures' insisted President Biden, pledging a peaceful transition. Many fear America’s experiment in democracy will be tested to destruction, but the majority of voters hope Trump’s Agenda 47 will improve their lives.

Either way, the influence of political scientists is likely to be marginal. Our analyses could be about Mars for all the difference they make. William Starbuck observed in The Production of Knowledge that 'Hundreds of thousands of talented researchers are producing little of lasting value'. He advocated instead that researchers challenge their thinking, and conduct social experiments to help people solve problems in reality.

This election challenges our thinking. In October, New York Times polls reported that 59% of voters thought 'the political system needs major changes', and 11% believed it 'needs to be torn down entirely'.

All politics are rough-and ready-experiments, tested in laboratories of public life. They are messy and unscientific, but affect life, death, and taxes. Failed experiments end careers, governments, states, or entire social systems.

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson called independence from Britain a democratic experiment. Alexis De Tocqueville urged Europeans to learn from it, while advocating a 'new political science' to

instruct democracy … to substitute little by little the science of public affairs for its inexperience, knowledge of its true interests for its blind instincts; to adapt its government to times and places

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835

States are the product of experiment, working hypotheses and models of how to govern. North and South Korea, the United States and the People’s Republic of China are all alternative models, as well as political laboratories.

Over centuries, liberal democracies have developed methods to improve political experiments. They have done so through impartial rule of law, representative assemblies, civil liberties, universal education, economic freedoms, regulatory bodies, judicial review, transparency, peaceful transfer of power, democratic norms, and electoral contests over competing visions.

In this election, American voters emphatically chose to change their model of the state. In re-electing Trump, they backed plans to cut taxes, slash regulation and renew 'American Civilization'. Knowingly or not, they join illiberal democracies that lead many to fear that the democratic model is breaking down, as it did with the American Civil War in 1861 and Germany's election of Adolf Hitler in 1933.

The United States has the most political scientists in the world. But its political system does not work for most voters. The US also has the biggest higher education sector, producing ideas and professionals that run the system.

There is some truth in Matthew Goodwin’s argument in Values, Voice and Virtue: The New British Politics, that Trump’s re-election, like the rise of national populism across Europe, is a response to university-educated progressives, whom he calls a 'new elite'.

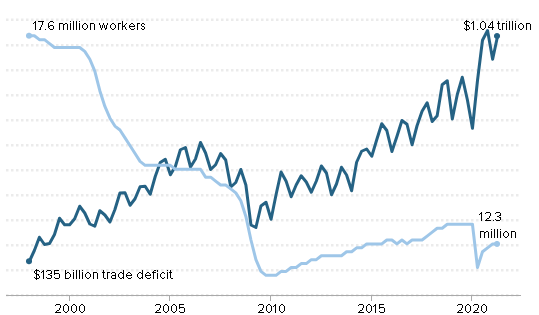

Decades of political experiments have resulted in deregulation, globalisation, widening income inequality and decreasing political trust

But the election of Trump is also a response to decades of political experiments informed by universities’ business and economics departments. This includes deregulation and globalisation that transferred manufacturing jobs to low-wage countries, and contributed to widening income inequality and decreasing political trust.

Recognising politics as social experiments and states as social models should empower political scientists to help citizens improve the 'democratic method'.

Politics is difficult and demanding, yet we do little to teach practical politics and the skills citizens need to conduct their experiment in self-government, including the ability to question the thinking of politicians and professionals who run the system.

This means developing nonpartisan, pluralistic political literacy and civic education in the community, schools, and the new media landscape.

It means ensuring that students and researchers are challenged by competing visions of society. They need to engage with views different from their own, not in the abstract, but through respectful debate about contentious issues.

It means producing impartial, nonpartisan research on issues that should concern citizens and making it accessible for debate in public forums without fear.

It also means seeking better models for solving social problems, locally, nationally, or internationally. We must help citizens, practitioners and policy-makers to experiment on how to bring about better outcomes.

We do little to teach the skills citizens need to conduct their experiment in self-government, including the ability to question the thinking of politicians who run the system

These are big tasks, requiring collective effort. But there are many models of civic education and engagement, democratic innovation and social reform from which to learn.

Many scholars are working on ideas and institutions that inform President Trump’s programme, through the America First Policy Institute, Project 2025 and Atlas Network, all 501(c)(3) non-profit, non-partisan research institutes. I question their impartiality, but they demonstrate that political scientists should not be afraid of helping citizens strengthen democratic governance in practice.

There is a clear line between being a political partisan and a facilitator, animateur, educator and researcher. Scholars may enter the political sphere as advisers, advocates, citizens or candidates – as many do – but it is important to keep these roles separate.

Election campaigns are a fusion of emotions, personalities, ideas, and organisation that test more than competing visions. Indeed, they test:

Trump met the first of these tests. However, winning did not prove he can meet people’s needs, solve problems or govern well, or that the system is effective. A smooth transition enables Jefferson’s experiment to continue, but it will take much more to create better outcomes. Almost $16bn was spent on the 2024 federal elections before anything has been done about the issues raised. Political scientists must work with citizens between elections to improve democracy to meet people’s needs better.