In Kazakhstan’s recent presidential elections, incumbent President Tokayev won an overwhelming majority, further consolidating his rule. Tokayev preaches democratisation. Yet, as Bakhytzhan Kurmanov argues, the elections were hardly democratic, and the reforms he proposes may mask an intent to strengthen his own position rather than empower Kazakh citizens

Riots in Kazakhstan during January of this year revealed its citizens' discontent with the country's authoritarian regime. The influence of the country's first president Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled from 1991 until 2019, still casts a long shadow.

With help from the Russian and Collective Security Treaty Organization, current President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev was swift to quell the January protests. He restored order, and arrested the head of the national security committee, Karim Massimov.

Tokayev removed former President Nazarbayev from Kazakhstan's national security council. Then in June 2022, by means of a constitutional referendum, Tokayev stripped Nazarbayev of almost all his constitutional privileges.

During this referendum campaign, political opposition was largely absent. What's more, it was marked by widespread state propaganda across social media.

Tokayev has actively embraced democratisation in Kazakhstan – on the surface, at least. This apparent trend towards democratisation is one we can see across various authoritarian regimes. As Alexander Dukalskis notes, authoritarian regimes need to promote a good public image to foster their legitimacy.

Tokayev has announced his intention to build a 'New Kazakhstan' – more democratic, and with fairer economic conditions

In spring 2022, Tokayev announced the beginning of Kazakhstan's transformation into a 'second republic'. This republic would build a more democratic state and create fair economic conditions for the people – a 'New Kazakhstan'.

State Counsellor of Kazakhstan Yerlan Karin is responsible for developing domestic policy. In September this year, he announced that the June referendum had indeed rendered Kazakhstan a true democracy.

Six candidates ran in the 20 November presidential elections. Unsurprisingly, they did not offer Kazakh citizens a genuine democratic choice.

For a start, the election rules did not allow self-nomination. Candidates had to run either as representatives of political parties or of non-governmental associations. So the political system in Kazakhstan therefore effectively excludes participation by an opposition candidate. This meant that Tokayev was up against five candidates who were either not well-known by Kazakh citizens, or not genuinely contesting the election.

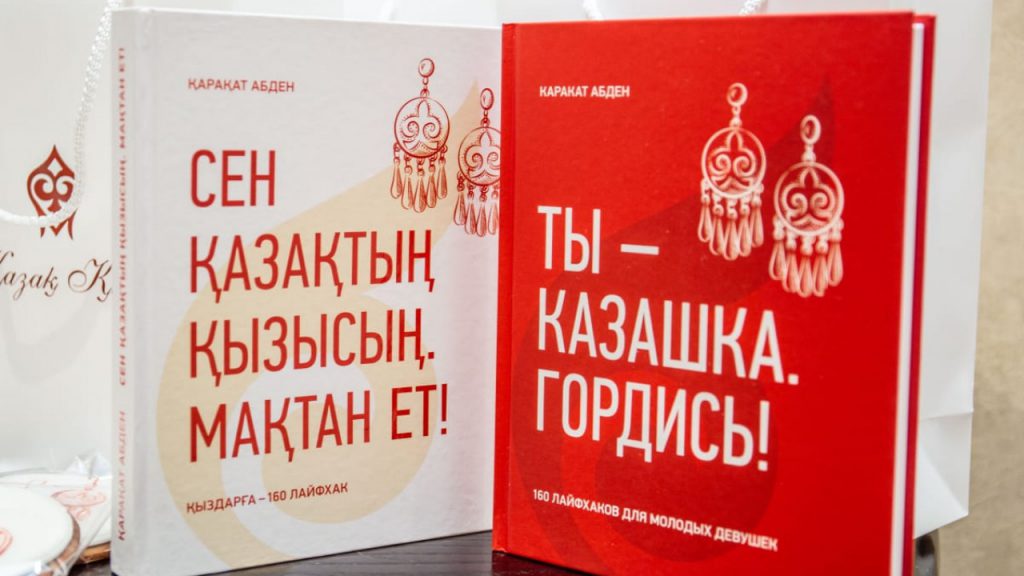

The candidate list, which included two women, was intended to constitute a broader demographic representation of Kazakhstan. One candidate was Karakat Abden, who caused a flurry of discontent by preaching traditional values for Kazakh women. Before running for president, Abden had worked for ten years in the Kazakh civil service and was a member of the ruling Nur Otan Party (now Amanat).

In television debates, Abden proposed imposing a massive tax on Kazakh women marrying foreigners. She even published a book containing such claims as:

Kazakh girls have never disobeyed or defied a man, as is customary in the West, and we're not fond of feminism. We don't need it

Karakat abden, You are a kazakh woman: be proud!

Other candidates ran rather curious election campaigns. The Auyl ('village' in Kazakh) party nominated Zhiguli Dairabayev. This candidate attracted attention for a video in which he 'broke' a mutton bone with his palm during a feast at home. Nurlan Auesbayev is leader of the oppositional National Social Democratic Party (OSDP) and a former member of the Communist Party. He will likely be remembered for his unsuccessful attempt to erect a monument to Lenin in the centre of Astana.

None of the candidates dared oppose, or even criticise, Tokayev's policies during the campaign. Tokayev didn't even bother to take part in televised debates, sending his representative Yerlan Koshanov in his stead.

At the previous presidential elections in June 2019, Tokayev gained 70.96% of all votes. These elections attracted widespread public dissatisfaction, and resulted in massive protests around the country. This time around, Tokayev won with an even bigger 81.31%. This reflects action on his domestic promises, and his balancing of foreign policy.

The 2022 presidential elections, of course, took place against the background of heightened geopolitical tensions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Tokayev reaped the benefits of this to prop up his political position.

While he stresses strategic cooperation with Russia, Tokayev is also urging Kazakh citizens to welcome Russians fleeing military conscription

After hosting the Central Asian summit in Astana in September, Tokayev positioned himself as a skilful diplomat. He is uniquely placed to manoeuvre between Russia, the West, Turkey, and China. During this latest election campaign, Tokayev flew to Samarkand in Uzbekistan. At the Turkic-speaking countries’ summit, he proclaimed his respect for territorial sovereignty.

And Tokayev meets regularly with President Putin – his first trip after inauguration was to Moscow on 28 November. There, he stressed the success of Russia and Kazakhstan in constructing mutually beneficial strategic cooperation in trade and other areas. At the same time, Tokayev urged Kazakh citizens to welcome into their country Russian draft dodgers fleeing partial mobilisation.

Elections without a real opposition can hardly be said to demonstrate the Kazakh President's desire to democratise the Astana regime. Yet, the results of this election may well reflect the public mood, and Tokayev's genuine popularity.

All in all, Tokayev seems to have consolidated his rule after a convincing election win. However, his domestic agenda of political and economic reforms will now be sorely tested. Research on Open Government in Central Asia shows that non-democratic rulers in authoritarian regimes may use democratic reforms to consolidate their power rather than to empower their citizens. This may well prove the case during construction of the New Kazakhstan.

[…] and social justice, Tokayev’s actions were aimed at dismantling Nazarbayev’s power and legitimising his rule until at least […]