Using a test case of social welfare policy, Despina Alexiadou argues that if we want to understand the policy choices of different governments, we should start by analysing the social class composition of their ministers

Can governments, made up of wealthy politicians, represent the average citizen?

Some people suggest that unless politicians share citizens’ life experiences, they cannot appreciate the concerns of their voters. Others argue that politicians aren't necessarily better representatives of voters simply because they share a gender, religion, disability or background.

Some people suggest that unless politicians share citizens’ life experiences, they cannot appreciate the concerns of their voters

So, can cabinet ministers' class background predict changes in governments' social welfare policy? And can it influence governments' responsiveness to the social welfare preferences of lower income earners?

Across countries and political systems, members of parliament are significantly more educated than citizens. They hold views, and policy preferences, that diverge from those of the average voter. They are mostly male, representing primarily the professional classes and under-representing the working class. Legislators with business or political backgrounds tend towards more conservative economic policy initiatives. Legislators with working-class backgrounds, or backgrounds in non-profit sectors, tend to favour more generous welfare provision.

I analysed new biographical data from the 1950s onwards, on cabinet ministers from 18 economically developed parliamentary democracies. With it, I investigated the descriptive and substantive representation of cabinet ministers across countries, and time.

At the descriptive level, those with legal, political and academic backgrounds have dominated parliamentary cabinets since 1945. Ministers with a labour-movement background used to be common, but their numbers have declined significantly over the last two decades.

Clearly, parliamentary cabinets have never represented society in descriptive terms. It seems, too, that they are becoming even less representative over time.

Since 1945, politicians with legal, political and academic backgrounds have dominated parliamentary cabinets

However, focusing on education alone, or on working versus non-working-class ministers, doesn't show us the full picture. We need to understand fully whether politicians’ social class does indeed play a role in representation. Non-working-class ministers might still be responsive to the welfare preferences of working-class citizens if they have personal, professional experience of lower-income earners' everyday challenges.

Highly educated sociocultural professionals, such as teachers and social workers, tend to favour generous welfare benefits because of their professional experiences and interactions. In contrast, liberal professionals such as lawyers, executives and bankers have a distinctly pro-market outlook. These people tend to prefer a smaller welfare state. Importantly, sociocultural and liberal professionals are the largest socio-economic groups of politicians in government.

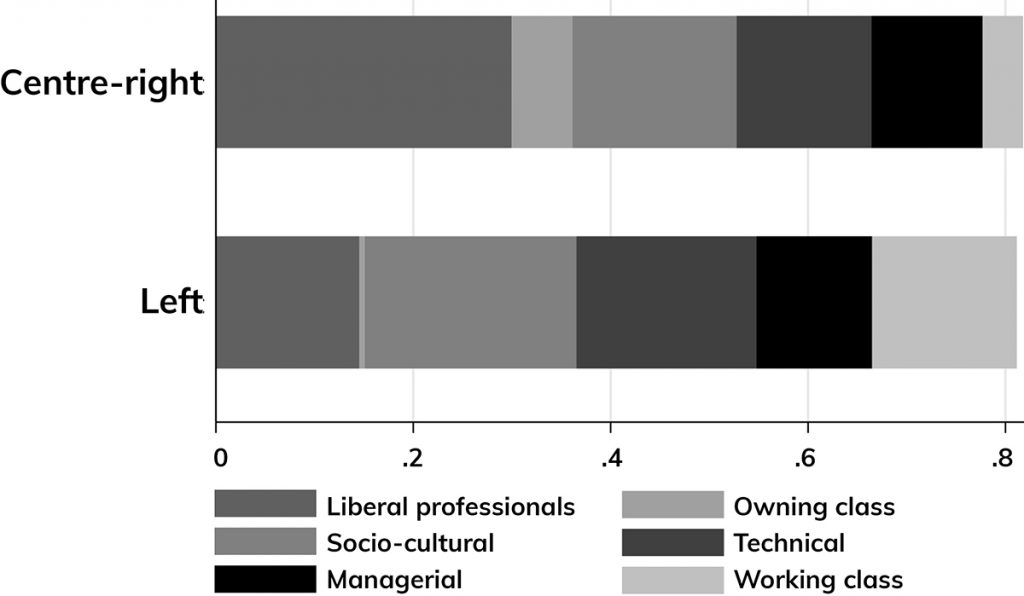

Building on the class schema proposed by Daniel Oesch and Line Rennwald, I calculate the percentage of cabinet ministers belonging to six social classes. The figure (above) shows the breakdown of cabinets’ social class composition by party family (centre-left and centre-right).

Over a third of cabinet ministers in centre-right cabinets are liberal professionals. Together with the owning class, they constitute almost 40% of cabinet ministers. In contrast, the largest class groups in left-wing governments are sociocultural and technical professionals. Liberal professionals constitute less than 20%, on a par with the working class.

At the substantive level, evidence suggests cabinet ministers' class background predicts how responsive governments will be to voters' welfare preferences. It also suggests how willing they will be to change the levels of social welfare benefits.

It matters whether a government has more ministers with a background in the humanities or education rather than law or business. Cabinets with a higher number of working-class and of sociocultural professionals are associated with positive changes in welfare generosity. Cabinets dominated by liberal professionals, by contrast, tend to support welfare cuts.

It matters whether a government has more ministers with a background in the humanities or education rather than law or business

Moving from a cabinet with no working-class ministers to one with 40% would result in a 20% increase in welfare generosity. In cross-country comparative terms, this amounts to a change from British Conservatives under John Major to Australia’s Labour government under Bob Hawke.

In terms of policy responsiveness, I find that welfare preferences of lower-income citizens are associated with changes in welfare generosity only when more than a third of cabinet ministers are sociocultural professionals. This means, in practical terms, that social-democratic governments in Norway or Portugal are much more likely to recognise the welfare preferences of poorer citizens than those in Austria or Spain.

In terms of the substantive effect, a unit increase in welfare preferences results in 0.05% in welfare generosity. This means that if preferences for higher welfare benefits increase from 20% to 50%, welfare generosity will increase by 1.5 points, or 4%, as long as a third of ministers are sociocultural professionals. By contrast, the top 10% of earners has a positive, and statistically positive, association with welfare generosity, independently of cabinet composition.

These findings have implications for the role of class composition in the formation of cabinets. It's true that we cannot, at this point, interpret an association between class background and policy in a causal way. But one wonders to what extent the professional backgrounds of ministers are considered in their appointments.

Do prime ministers and party leaders, for example, appoint ministers with a sociocultural or working-class background because they want to increase benefits? The findings also raise questions about representation. It remains to be explained why cabinet ministers with a background in liberal professions (banking, law and business) are associated with cuts in social welfare. Nor do we know whether this association is linked to revolving-door politics – or to personal and partisan ideology.